Greylag Geese: Our Arctic Ambassadors

As the colours of Autumn develop in the woods and fields around us, Jim Crumley looks back at one of his most sacred memories of nature at this time of year…

Somewhere deep within me, I will always carry the memory of that October day far out on the Moine Mhor, the Great Moss of the Cairngorms plateau, a day of such prime and primitive autumn that it was already spectacular before the moment occurred that made it something more or less sacred in my mind.

I was walking with an old friend, the writer and mountaineer David Craig. The yellow light of the day and the tranquil grandeur of the sheer space of the plateau washed over us in waves. I have never encountered quite such an atmosphere among the mountains of Scotland before or since.

It seemed to me that when we talked we spoke more quietly than normal, and whether consciously or not that we walked more softly than normal, as if somehow our very presence wounded the deep peace of the hour, and we were trying to mitigate the wound. Then I noticed that our footfalls were the only sound. I stopped and said, “Listen!”

We listened. There was no other sound…

Utter silence is so rare in a land like ours that its presence had stopped us in our tracks. There was no sound of falling water, nor of wind. We were too far out on the Moss for civilisation’s voice to trouble us, and no aircraft droned in our sky. No dog barked, no deer coughed, no bird or bee uttered a note, there was nothing, nothing at all to impinge on the blessed silence.

It lasted, I suppose, no more than a couple of minutes, and the thing that ended it was the sound, right at the very edge of my hearing, of a skein of south-making greylag geese. We were at around 3500 feet, and the skein was at least 2000 feet higher, but clearly visible in binoculars. In that supercharged mountain air and the absence of competing sound, their voices reached us as a silver rain of whispers.

Anyone who has heard a greylag goose at close quarters will know its voice for a thing of ungracious clamour, but then and there they were ambassadors from the Arctic edge sent to impart grace on a moment of mountain sanctity, and my gratitude to the whole tribe of greylags wherever I encounter them is undiminished over the intervening years.

Scotland harbours two distinct populations of breeding greylag geese, a native one in the north and west of the country, and a reintroduced one which has thrived in the old haunts of the species in the south and east. They look and sound alike, but behave utterly differently.

If you are accustomed to the greylags that course between the small lochs around Arthur’s Seat in the middle of Edinburgh and dignify that hoary Old Town silhouette with their flights, then the demonstrably uncompromising wildness of a nesting pair on a tiny island in Broadford Bay or the head of Dunvegan Loch on Skye is likely to take you by surprise.

Add to these the massed ranks of the Icelandic population, around 95per cent of which spend winter in Scotland (and that amounts to somewhere around 90,000 extra birds), and there is no good reason for not finding yourself close to a family or a skein or a great horde of greylags somewhere in the course of the wild year.

It will come as no surprise to you to learn that I am thirled to the wilder sept of the greylag clan, thanks primarily to that old Cairngorms day. But also I am an instinctive haunter of the islands of the west and north for all my east coast mainland origins, and so I know where I can expect to encounter wild pairs with an obedient brood of say, half a dozen goslings paddling into the distance when I have accidentally disturbed their sunlit midday doze on some skerry or other.

They display a hair-trigger wariness!

The brood I watched over a few July days on Broadford Bay this year was typical of the native breed on their home territory. I was staying nearby and morning and evening I went to look for them, and even though they are accustomed to people wandering far out into the bay at low tide, gathering bait or fishing off the rocks, or readying boats for the turn of the tide or canoeing in the shallow waters, they display a hair-trigger wariness and it is very difficult to get close.

They hone that wariness keeping a look-out for the otters, for tourist dogs, and they watch the sky too for the big black-backs, the occasional skua, the peregrines that regularly strafe the gull-and-wader hordes when they cluster together at high tide, and what must be the terrifying (and ever more conspicuous) skulking presence of sea eagles, for Skye is once again a pre-eminent stronghold of that particular coastal pirate.

In one way, however, this new relationship between goose and eagle is simply a resumption of the way things were, of old hostilities, for historically Skye was a sea eagle heartland, far outnumbering the island’s golden eagle population. Robert Gray in his classic 1871 book, The Birds of the West of Scotland, provides evidence of a keeper who killed 57 sea eagles on one Skye estate in nine years, and another in Wester Ross who killed 52 in 12 years. One Captain Cameron of Glen Brittle told him that of 65 eagles he had killed “or caused to be killed”, only three were golden eagles. The sheer numbers not only explain the sea eagle’s inevitable extinction but also indicate just how familiar it once was to something like a breeding greylag goose. A gap of the better part of one hundred years will not have diminished a Skye goose’s awareness of just what that bird shape means.

Geese on a winter roost near Stirling

Perhaps more surprising to us now is the fact that the greylag almost vanished from Scotland itself in the 1930s, and for exactly the same reason. It was shot in numbers that were simply not sustainable. It clung on in a few places like Skye and the other islands of the west, and a long, slow improvement in grassland management began not a moment too soon, and the long, slow haul back from the brink of extinction moved apace.

Migration is a fact of goose life, whether it means the wearying trek down the north Atlantic in October and November and back again in spring, or shorter summer migrations among native breeders to established moulting sites, journeys that are not always easy to explain. Why, for example, desert Slimbridge in Wiltshire in favour of Hogganfield Loch in Glasgow? Or Yorkshire for Loch Leven in Kinross?

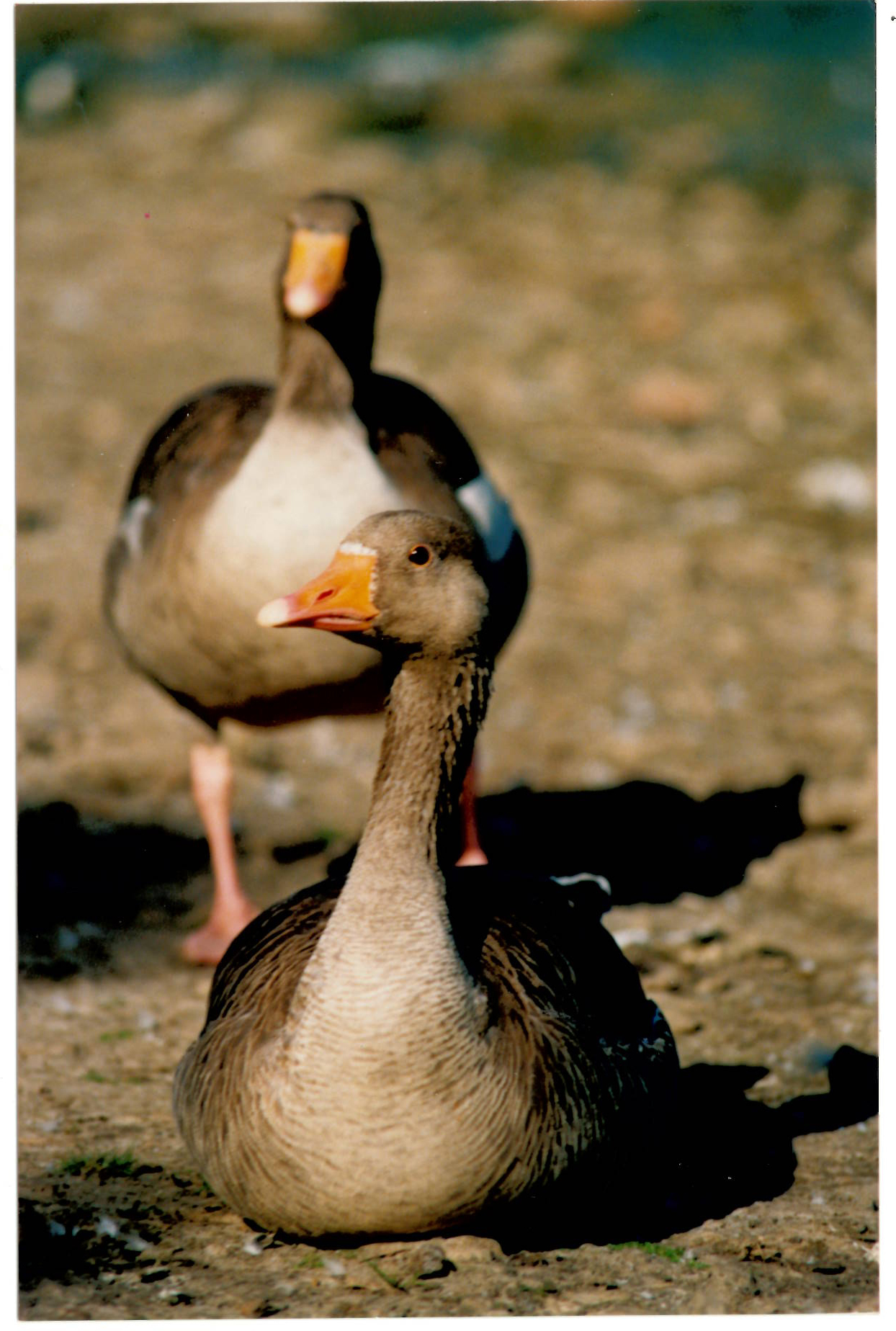

Moulting birds are always restless, always working at their plumage, and in the process, they create intriguing photographic possibilities. I am no-one’s idea of a wildlife photographer but settle yourself near a summer moult and the pictures more or less create themselves. Here is a pair dozing on a warm afternoon, rounded as pebbles, and beautifully patterned in every shade of brown from almost black to palest fawn, and no discernible shade of grey at all. Suddenly a car pulls up 50 yards away and both their necks straighten and one bird stands so that the head of the nearest bird is sharply defined against the breast and belly of the standing bird. One irresistible composition evolves into another.

Another goose is working vigorously among its underwing feathers, then straightens and stands on one leg, leans left and stretches its gleaming white-edged right-wing out along its extended right leg. The pose is comical enough without the embellishment of a single downy white feather that still adheres to the tip of its beak. You find yourself smiling a lot in the company of geese.

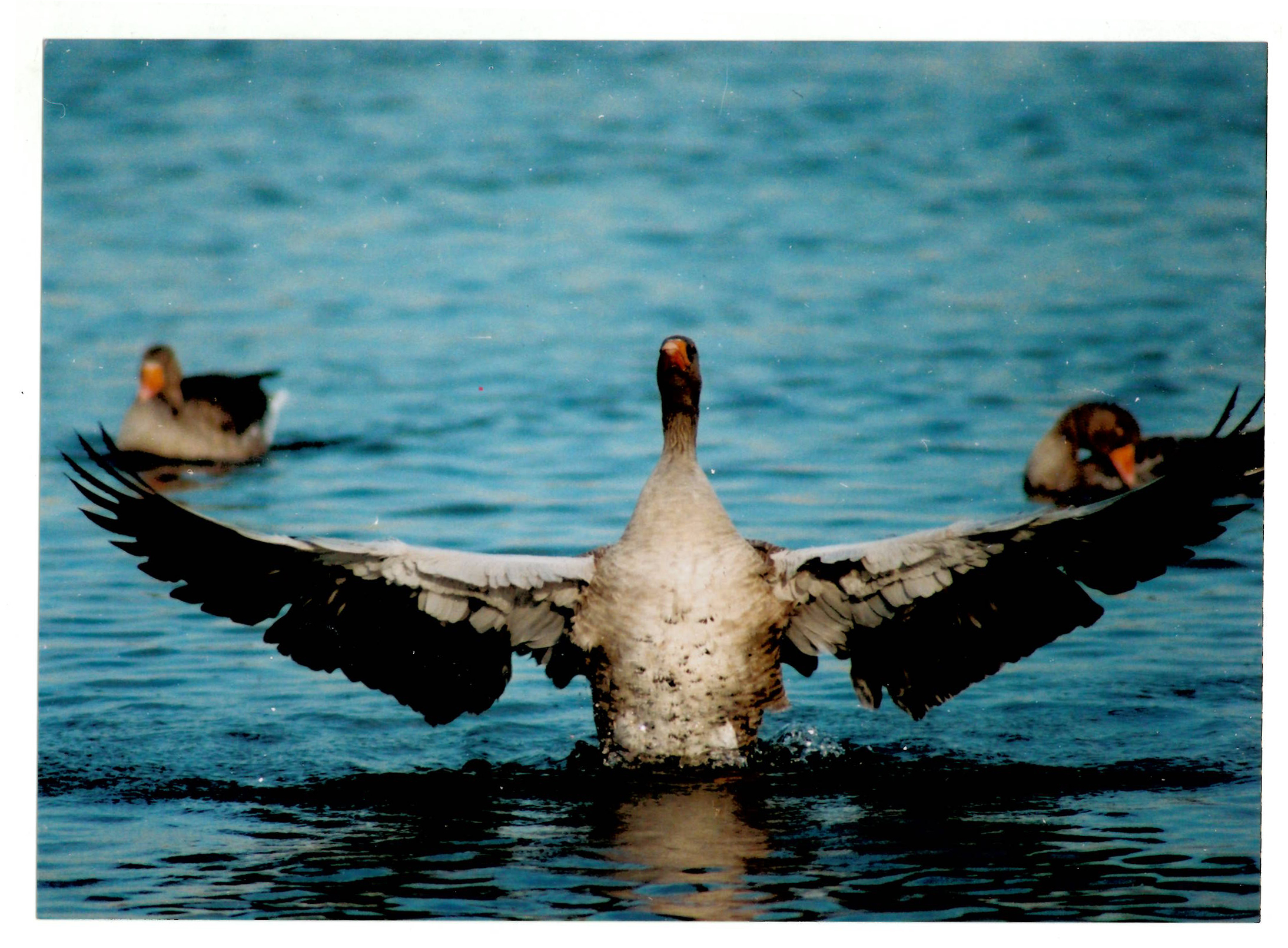

Midwinter

Midwinter and an altogether greyer looking bird comes in to land on a winter roosting water. Before it settles on the surface it throws its wings wide and “stands” on its tail for a moment, in the manner of swans, then whips the wings towards each other in front of its face so that the tips of the primary feathers almost touch, and their shadows lie in bars across its breast. I never saw a swan do that, and I find myself smiling again.

If you are lucky enough to live near one of those preferred winter roosts (these slowly move southwards to Lowlands and Borders lochs and firths after initial large gatherings in the north at such as Loch Eye in the Black Isle, and more generally from Shetland down the east coast to Aberdeenshire), the spectacle is often one of geese in their thousands.

And right now is the time to get out and start looking and listening. The migrating flocks are already on the way, and no matter that thousands will have been shot in Iceland in late summer, and no matter that 20,000 more will be shot under licence in a Scottish winter, they still move across the land in teeming, thrilling clouds of birds.

And if you are high in the hills especially in the north and east of the Highlands, watch for the still higher skeins that follow the big glens south-east and south, for these are their route-markers, the familiar landmarks they work with year after year, and century after century.

The restless march of the greylag goose through the seasons is one of our most reliable rituals of the wild year, and it’s never dull. And every now and again – say, once in a lifetime – it offers up a moment like the one that broke a mountain silence, one of nature’s most extraordinary gifts.

You can read more of Jim Crumley’s Scottish wildlife columns online here, and each month in The Scots Magazine.

Subscribe to The Scots Magazine today for more from Jim Crumley >>