Tom Weir | The Happy Glen

Exploring in the Grampians, Tom Weir went to meet the people who have chosen to live so remotely in the deceptively sleepy glens where disaster can easily befall the unprepared

“I’ll meet you at Prosen Bridge at 11 a.m.,” I had said to Iain on the phone on Friday.

Now I wasn’t so sure, as the pleasure of a fine Saturday morning was dimmed by layers of mist thickening to fog, making the ten miles on each side of Perth slow going.

It was delight, therefore, to drive suddenly into sunshine, and above the drifting skiffs of mist see skeins of geese swinging against blue sky, and peewits by the hundreds gleaming on newly-ploughed brown furrows.

Spirits rose in Kirriemuir at the sight of the wee town under the autumn colours of the hills, and in no time I was bearing down on Iain standing by the bridge. The time was within a minute or two of 11 a.m.

It was our first meeting since the Shiants trip described in the October issue (which you can read here). Now we were off to enjoy a walk in a glen that was new to Iain. A jaunt up to the Airlie Memorial Tower, perched 1245 feet above the division between Clova and Prosen, seemed a good place to begin.

The first impressions of Prosen bursts

upon you

“Great,” lain was exclaiming as we pulled past the Scott Monument, where the first impression of Prosen bursts upon you, rounded hills, heathery slopes, green meadows each side of a river hung with birch, oak and rowan.

I always think of Prosen as being more like one of the splendid glens of North Yorkshire than most of the glens in Scotland, with its gentleness and the feeling of a man-made landscape of woods and fields, lain walked across to the monument which commemorates Scott and Wilson of the Antarctic, who spent a holiday here before setting off for their journey to the South Pole.

Climbing through the steep pine wood, I was thinking of Scott and Wilson who probably came up here talking over their plans for the forthcoming polar trip.

Suddenly we were out of the trees, and looking at a junction of two worlds.

Southward the wooded ridge below us fell away to the agricultural quilt of Strathmore, a patchwork of pale yellows and browns.

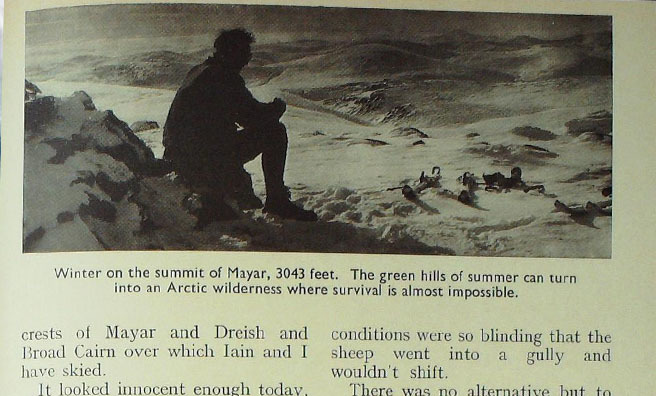

Northward the low roll of Is rose ever higher to the 3000-ft. crests of Mayar and Dreish and Broad Cairn over which Iain and I have skied.

It looked innocent enough today, and we have been lucky enough to have had perfect conditions of deep powder snow and sunshine for our traverses. But we knew just what a killer the wild country stretching from here to Braemar could be.

Not as innocent as it looks

A friend of Iain’s, who had explored with him in Greenland, died of exposure with his girlfriend up there on Jock’s Road last winter.

In impossible conditions mountain rescue teams and dog handlers searched for a week before the bodies were found. The victims had been caught out by a turn-round of wind on the 12 miles of hill separating Glen Doll road end from Ballater.

I recalled, too, the New Year of 1959 when five members of a Glasgow hiking club died on that same crossing on a day of blinding wet snowfall when we had to abandon ski-ing in the intolerable conditions.

Burly Archie White of Spott Kami blocked our way with a flock of rams as we resumed our journey up the glen. I mentioned blizzards to him.

He cast his mind back to a January storm of the 60s which suddenly struck a shepherd of his bringing a flock of sheep off the bill. It was getting dark, and the conditions were so blinding that the sheep went into a gully and wouldn’t shift.

There was no alternative but to leave them. The worst happened. It snowed steadily for days on end and hard frost set in. Out of 110 which went in; only one came out alive, the others had died of suffocation.

“I think the survivor had got under a bank, maybe, and managed to get some air. We called it ‘Seventeen’ after that, for it had been buried for seventeen days. It was a three-year-old ewe, and it must have been hardy.”

Archie has 900 ewes on 2500 acres, and 40 Aberdeen Angus cattle. His grandfather, William, was one of the pioneers of the breed in this area, and he took me over to the park to see the sleek, shiny black beasts.

Beauty treatments for rams?!

We also had a look inside the steading where big rams were getting beauty treatment as horns were fifed and fettled up to bring out their whiteness. I didn’t know that by applying heat to the horns the double-curl can be improved, and this may help to lift the price to £120-£150 each.

Getting the rams ready was a family affair, and his daughter Patsy and wee grandson were helping.

“The rams are a sideline, a kind of hobby. My neighbour, Stewart McIntosh, does much better. He got £2200 for one last year, and one of his made £2000 this year. You’ll find him at Glentairie Guest House with his wife, or up at the farm working.”

Stewart was away in Dalmally at a sheep sale, we discovered, so we took the hill track that goes up behind Glentairie, following the west side of the attractive wooded gorge made by the Burn of Inchmill.

Our target was the top of Balnaboth Craig which is mostly grassy sward on this side.

It was delightfully warm up there in the sun, looking across to the “Minister’s Track” which links Glen Prosen village to Glen Clova, or tilting our eyes steeply downward to the ruined chapel, parklands and home farm of Balnaboth.

Descent was steep to get down there, by a ride of long heather breaching the pines. A green woodpecker was “yapping”, and redwings and fieldfares were flighting from the ivy of the 17th century chapel as we enjoyed the grassy alps and natural birches of this delightful spot.

Nor had I any feeling that I was trespassing, for Captain Alastair Ogilvie McLean had given me permission (on a previous visit) to go where I liked.

The ghostly Green Jean

On the former occasion a few weeks before, he had taken me along a narrow stone corridor to his office.

“This is the old bit of the house. It’s about 400 years old. It may even have been an ancient keep. It looks a good place for a ghost, and we have one, ‘Green Jean’. My wife has seen her—an old body dressed in old-fashioned clothes, with a shawl or plaid crossing in front. She saw her just after the birth of our son in August 1950. We have three of a family, the other two are daughters.”

Captain McLean explained to me that he was really a West Coaster, tracing back to McLean of Coll whose line has produced so many soldiers and sailors.

His father, in the Black Watch, was killed at Gallipoli, as was mine. McLean himself served in the Black Watch and prefers a kilt of Ogilvie tartan to any other dress. A homely man, easy to talk to and without pretence, he told me of the pleasure he finds in Glen Prosen.

“My wife from Wiltshire is in hospital just now, but she feels the same affinity to the place as I do. She overworks, because we have to manage with so few staff. My grandfather used to pay over a dozen people to run this place. We have to manage with a gamekeeper and an overseer. We sold the upper glen to the Forestry Commission and passed the home farm over to a tenant. I enjoy trees. I’ve planted about 400 acres.”

As we talked I was shown the ramifications of the old house, which was added to in 1830, and contains a fascinating mixture of styles and furnishings, each with its bit of history. I was shown the room where Barrie worked on The Little Minister, and allowed to read some of his letters under a glass cover.

“Yes, the older one gets the more one thinks back to the past. This house is virtually a museum built up by those who have gone before us. These are difficult times, but we hope the owner’s loss is the tenant’s gain. I am modernising old houses, and I’ll let them to pensioners, perhaps in return for some work. There is pleasure in that.”

A surprising sale

At Cormuir across the glen I met Stewart Mcintosh, newly back from Dalmally where the sale had been a surprise.

“The sheep made far more than they should have done. And the same is true of beef. The cattle are fetching too good a price. No fanner should be complaining this year. Come inside and meet Mother. She’ll give us some coffee.”

She did, and she also put down on a tray some of the most delicious rock cakes I have ever eaten.

We were in the parlour, and I couldn’t help noticing the silver cups and rows of medals behind glass. I got up to look at them and the photograph on the wall of a cheery-faced man in a tammie talking to the Queen Mother.

“Yes, that’s ma father. He’s aboot seventy there, and it was taken at Birkhall after he had walked across Jock’s Road wi the Black Watch from Dundee.

“Father had been a sniper at Ypres. He was buried last February on a day sae cauld that the Black Watch piper couldna work his fingers properly. He had never been a regular soldier, but he loved everything to do wi the Black Watch.”

The parlour still held his personality. I noticed one medal had eight bars on it.

“That’s the Donegal Medal. Father is the only marksman in the small bore rifle club to have won it eight times.”

We were getting on so well that Stewart decided to come with us up the glen and point out some landmarks. We stopped two miles up at the big white shooting lodge.

“I love the grouse season. It’s great sport, and I’m a keen shot myself. It wis bonnie in the auld days of a fine mornin when you took a string o ponies wi the lunch baskets on panniers to the butts. It’s mechanisation now. There’s onlv three families livin between Cormuir and the heid o the glen.”

Up the deteriorating track we went to the rocky headwall of the glen whose corrie is now planted with Forestry Commission trees. Formerly part of Balnaboth, the Commission has sold the unwanted part of the high ground, so that from the bare tops nothing but deer forest, stretches ahead all the way to Deeside in high, heather country where the ptarmigan reaches its highest density in Scotland.

“They say it takes forty years tae be a glenner,” chuckled Stewart. “I still feel I belong to Cormuir, though it’s five years since we gave up living there to take the wee guest-house of Glentairie. Frances, my wife, enjoys catering and cooking and running the shop. It’s a funny thing, but most of the people who come to stay wi us are English fowk. It disnae seem to appeal sae much to oor ain fowk, maybe because the scenery’s too tame.”

Meeting the glenners

Next door, however, was Fifer Iain Nelson from Saline, who is a real enthusiast for Glen Prosen. Iain is one of Scotland’s most accomplished master potters, and he enjoys it here because he can get on with his work with few interruptions. For recreation he has half an acre of alpine garden and vegetable plot.

“I got this cottage when I came back from America in 1970 and built a kiln. I had been thinking of setting up a pottery here while in the U.S.A. I knew the glen well from coming here as a grouse- beating student. I thought of it as a full-time job, but took a job in Edinburgh Art College which I find stimulating. It means that at week-ends and holidays I can do my own thing here. The work I do is mainly for exhibitions. I don’t go in for souvenirs.

“I like to think of the pots I make as well-designed pieces that can be put to use and not just ornamental. Right now I’m working under a certain amount of pressure for three group exhibitions in December, at the Open Eye Gallery and the 57 Gallery in Edinburgh, and in a Stirling gallery.”

Iain is 35, black-bearded, lithe and a bachelor who could be described as eligible.

A local man had described him to me as a man who is “not easy gotten to ken,” adding, “He maks great muckle pots wi little mannies on them keekin oot fae the side. Ken, ye’d think they were livin. And he sits for oors in the gairden pickin weeds, grapin awa at naething. The gairden looks a richt mess, then it blooms all of a sudden, and it’s the bonniest thing you ever saw wi a kinds o coloured flooers among the rocks.”

I saw what the speaker meant when Iain took me across his garden to his massive kiln of firebricks and brought out some of his “pieces”, wonderful things turned on the wheel first of all, then modelled with human heads and animals. There were tiny things, too, one an exquisitely-made little box for a dressing-table.

And just round the corner from Iain in Glen Prosen village, opposite the church, is another artist, Norah Cotogno, who is busy painting in oils for an exhibition in the spring.

She also designs and makes jewellery, using gem stones as centre-pieces. Despite the foreign-sounding name, Miss Cotogno hails from Alyth.

Originally she came only at weekends, but the price of petrol decided her to move in two years ago and try to make a living working full-time as an artist.

Her home is the old schoolhouse, containing the original fireplace and old swey. She has had visitors who remember when the lunch-time soup used to be cooked on that lire for the children.

A lonely life?

“No. The summer is busy. I have so many friends calling. I find life completely satisfying here. I used to work at Invergowrie, and I may have to take on a wee job if I get too poor. Meantime, with three cats and a garden and a place like Glen Prosen to live, I’m rich!”

Her sentiments were general in this glen of happy people.

You can read more of Tom’s escapades here, where a new column is published online every Friday.

- Tom at Kingshouse, Argyll with the crew from Weir’s Way