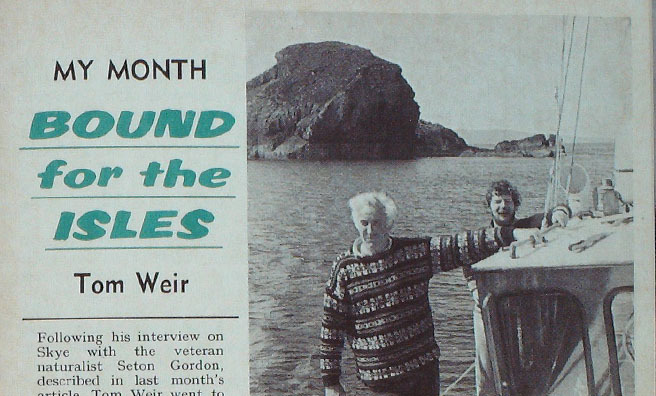

Tom Weir | Bound For The Isles

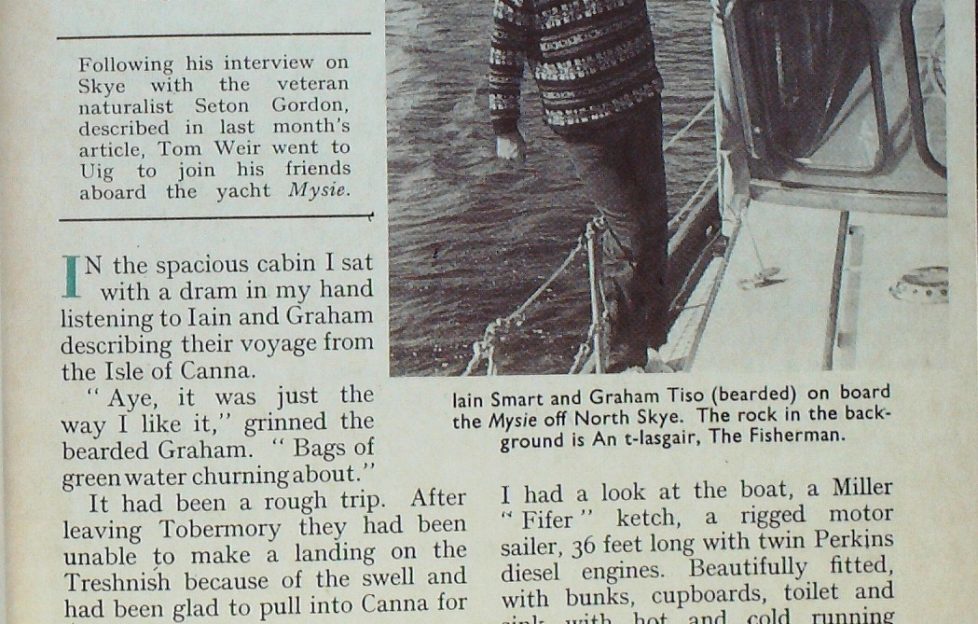

IN a spacious cabin Tom Weir sat with a dram in his hand listening to Iain and Graham describing their voyage from the Isle of Canna…

“Aye, it was just the way I like it,” grinned the bearded Graham. “Bags of green water churning about.”

It had been a rough trip. After leaving Tobermory they had been unable to make a landing on the Treshnish because of the swell and had been glad to pull into Canna for the night.

“Sailing in the Hebrides is very like winter mountaineering in Scotland,” opined Graham. “It’s always different. You learn something new every time.” He looked at me.

“I feel I know what to expect in the Inner Hebrides, but I’ve been to the Outer Hebrides only once before, so, as the consultant ornithologist, where do you suggest we make for in the morning?”

As he spoke he was thumbing the tide-tables to time our getaway.

The boat was a beauty

I had a look at the boat, a Miller Fifer ketch, a rigged motor sailer, 36 feet long with twin Perkins diesel engines. Beautifully fitted, with bunks, cupboards, toilet and sink with hot and cold running water; it was all the more impressive for being so shipshape.

Everything had its place, a wee library of books for light reading, reference books on sailing for immediate information on a separate shelf, charts in a drawer, tins of food under the cabin floor and perishables behind our seats.

Aloft in the wheelhouse there was radar, an echo-sounder, radio telephone and self-steering gear.

By the time we turned in we had agreed to make for the Shiants, and in the morning we were on our way before the mist had steamed off the green hills above Uig Bay where a pale disc of sun promised a good sailing day.

Engines throbbing, we turned north out of the bay, enjoying the sight of Benbecula’s only hill and in a mile or two were passing Prince Charlie’s Point where Flora MacDonald had brought the Prince disguised as Betty Burke after their sail from Benbecula.

Thoughts of history were dispersed when Graham set down my breakfast before me, a plate of ham and eggs which I ate on deck in the warmth of the sun, now unobscured. This was certainly the life for an old soldier.

As climbing men we were beginning to take notice of An t-Iasgair, an impressive rock stack about five miles west of Duntuilm.

It was an island of which I knew nothing, so it was a thrill to get in close and see its high cliff pierced by a hole through which we could see not only daylight, but silhouettes of birds perched on pinnacles within the opening.

Bird-packed ledges vibrated with the bugling cries

Soon we were under its lee, into aquarium-green water where Atlantic seals sunned themselves on low rocks, terns wavered and fulmars sailed back and fore.

But the big moment was when we rounded the next buttress and looked up on bird-packed ledges vibrating with the bugling cries of kittiwakes and the vibrating calls of innumerable guillemots. Green cormorants like gargoyles draped every rock, wings held out to dry in the sun like black flags.

“Plenty of depth here,” said Graham as we crept closer, looking for a place to drop the anchor.

The snag was the swell and the rocks on three sides of us. It left little room for error, and although Graham did drop anchor he was not happy at the holding. We retreated for a try round the other side of the island, but the wind was worse, so we left it and motored north for the Shiants, where Iain and I had spent a week in 1963 in one of our best-ever island trips.

So, three hours later, it was with a host of marvellous memories in our minds that lain and I stood in the stern while Graham edged the boat under familiar organ pipes of columnar basalt, orange-bright with lichen, where puffins hurried to and from hanging ribbons of green sward.

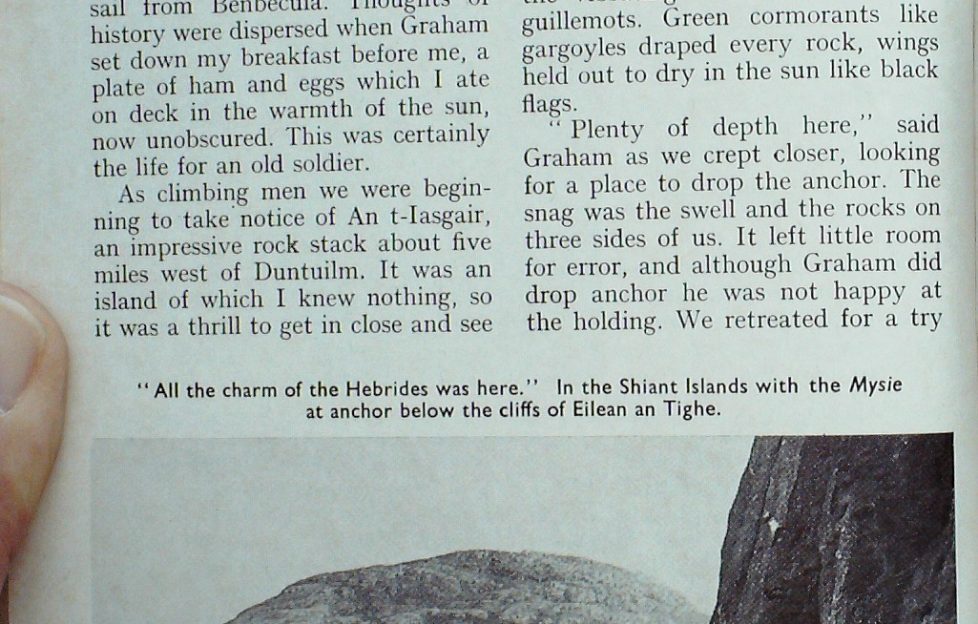

No arrival could have been more perfect; the Shiants were a colour slide of memory come to life— the fretwork of pinnacles known as the Sgeir, the natural arch which pierces the north-east tip of Garbh Eilean, and across tlie water from it, the lazy-beds of Eilean Mhuire ribbed sharply in striking vividness.

Anchor down, we were soon into the dinghy and hauling up on the gravel of the tidal strand between Garbh Eilean and Eilean an Tighe — island of the house.

We had camped beside it on our former visit, and to sharpen the memory we could see somebody sitting by a tent on our very spot. Iain vetoed the idea of going to see if the apparition was real. He was eager to traverse the exciting boulder fields under the cliffs of Garbh Eilean where puffins, guillemots, razorbills and hosts of shags were steeply perched as if waiting for us.

The three islands which form the Shiants are at the northern limit of the columnar basalt, which means that geologically they belong to the Inner Hebrides despite their proximity to the infinitely more ancient rocks of Lewis.

The boulder- held was made up of huge chunks of tumbled pillars forming nesting grottos for the countless birds whirring over our heads or groaning beneath our feet.

Puffins carried beak fills of tiny fish. Shags displayed their yellow gullets as they shook their heads angrily at us with hoarse curses. Five hundred feet up we were into a different world of singing skylarks, and looking on the view we remembered with such affection, to Harris and its skyline of lumpy peaks facing east across the North Minch to the strange monoliths of Sutherland, signposted by Suilven.

All the charm of the Hebrides was here in sights and sounds and scents, for we were now out of the sickly odour of the seabirds and amongst flowers. We were not alone on the hilltop, for half a mile distant along the ridge we could see two other people, armed with long poles which we took to be stakes for mist nets, used in the catching and ringing of birds.

Dropping down to the house on Eilean an Tighe we discovered from the Visitors’ Book that the people we had seen were members of a University Ornithological Expedition, and from the records it looked as if they were trapping quite a few stormy petrels which come to their burrows during the hours of darkness. We were delighted with the good condition of the house. Now equipped with Calor gas cooker &c., it is a much improved place from the dank dwelling we remembered 13 years ago. The house is used mainly by shepherds who come over for the lambing, dipping and clipping.

Ten families once lived here, the last of them departing for Harris in 1901. One was a girl of 22, who until then had never left the Shiants. Her world was 500 acres “fruitful in corn and grass,” to quote Martin Martin, who in the late 17th century said the cows were better than any he saw in Lewis or Harris.

An adventurous idea

Back at the dinghy. Graham had an adventurous idea. To return to the Mysie, he would get the outboard and motor the wee fibre-glass boat through the rock tunnel which pierces the eastern pinnacles of Garbh Eilean.

In the three-quarters of a mile approach I wouldn’t like to estimate how many thousands of birds scuttered out of the way of our dinghy, diving under our bows, walking on the waters, wings beating comically, or swimming out of reach, while overhead the air whirred with them.

Under the lee of the cliffs the projecting rock curtain cleft by the tunnel loomed ahead, echoing with the slap of the swell where the dark water swilled from side to side. Inside it was an echo chamber, eerie and mysterious as we went from light into darkness and out into light again.

We enjoyed it so much we were soon nosing round the corner to enter a narrower and darker tunnel, a cave possessed by an Atlantic seal which swam ahead of us until stopped by the solid rock wall of the island. Head and chest out of the water, it might have felt it was being cornered, so we judged it politic in our small craft to turn about and head back for the distant window of daylight.

We knew we had been in luck as we bumped back to the Mysie, for the sea was getting up and the wind increasing. So it was anchor up and westward to Harris, with a none too good weather forecast coming true as we passed the mouth of Loch Seaforth into the Sound of Scalpav, to enter the North Harbour and tie up in front of the most prosperous fishing village in the Long Island.

I was heartened by everything I saw

It was Friday night, and getting on for 9 p.m. when we anchored off Scalpay’s busy pier. Fishermen were still working on their boats as we cooked our evening meal over an hour later.

And the place was astir again on Saturday morning, long before most folks in towns have breakfast. It was a drizzly day, but the jersey-clad men didn’t seem to bother as they strode between pier and village.

Ashore, I was heartened by every-thing I saw. Lazy-beds grew oats and potatoes on the peat banks, cows were tethered and grazed safely above the rocks, there was a coming and going of lobster boats, and plenty of children talking in Gaelic as they played.

There were also the houses, many of them with well-kept gardens, and built to higher aesthetic standards than is normal in the Hebrides.

Graham asked a fisherman about the chances of getting a repair done to his self-steering gear. He directed him to the Red Cottage where he said his father might do it for him. Up there we found a young 83-year- old who took us into his well- equipped workshop where the job was quickly done amidst spinning- wheels and other items which Mr K. McLeod repairs.

I hen as soon as the repair was finished we were invited into the house for tea. It is a small world. In the house was another son who had been one of the crew of the fishing boat A’ Mhaighdean Herrich which had taken me to St Kilda in the mid ‘fifties. ” It was Roddy Cunningham’s boat.

Without him there would be no boats in Scalpay today. He is dead now, but his influence is still here. It was Roddy who showed us the way and kept the Scalpachs at sea.”

His father took up the tale. ” I was a fisherman myself, and happy as a seagull until I took thrombosis at 52, so I became a handyman. You know at the end of the war we had only four felt roofs in Scalpay. All the others were thatched. We had no roads.

“But in the days of sail there were live herring-curing stations here. You can see the remains of them vet. We were getting down, but look at the prosperity that’s here now, because the fishing was good after the war and the young men put their backs into it.”

Graham was impressed by the quality of the fishing boats and their smart trim. Of the fleet of a dozen ring-netters, half were built without financial help from outside. The remainder carried some Highlands and Islands Development Board investment.

The inshore men had their own lobster pond, and when I heard there were a hundred children in the primary school I was delighted, since the total influence here is Gaelic.

The bad time had been 1973-74, I gathered, with low prices and high fuel costs, but with prawns at £18 a stone nobody was complaining now. Out of a total population of about 450, 60 per cent, get a livelihood from fishing, hence the self- confidence of this community, who have sons in the Merchant Navy as well as in their home-based coasters.

We rolled and pitched against the south-wester

It was to North Uist we set sail til late afternoon in the face of a bad weather forecast, realised all too soon when we turned out of our snug harbour into a gurly sea and rising wind and driving rain. Time to take a pill, and follow it with another as we rolled and pitched against the south-wester. I didn’t feel unwell, but took Graham’s advice when he suggested a stretch out on the bunk, as lain was already doing since he was feeling slightly uneasy.

Graham was happy up there, navigating the boat through the rough sea in lowering mist and rain for four hours or so to hit the narrow entrance of Loch Eport, lower speed and turn east through rocky jaws. There was nothing snug about the bay called Bagh a’ Bhiorain where Graham let go the anchor, but he tested it thoroughly and pronounced it safe for the night however much wind and rough sea might tug.

Now we could get the pan on for our main meal of the day, eaten as usual about n p.m. The shipping forecast near midnight told us that the Force 6 would not die down for 12 hours, so we knew we were in for a long lie. It was certainly noisy in the fo’c’sle as the boat kept moving round its anchor with many slaps and bangs.

Thoughts in the morning were for an ascent of Eaval, 1138 feet and one of the most awkward hills to climb in Scotland for it is almost surrounded by water. By the time we had made up some fishing lines and were ready to go, its rocky pyramid was clear and flashes of sun brightened the green shores and sparkled the water.

It was low tide when we tied up the dinghy and set off along the shore of Loch Obisary which half-encircles the peak. A peregrine falcon beating high above us seemed a good omen as we traversed the flank of Burrival and continued in a half circle to strike up our peak.

First, though, Iain fished a burn for trout, while Graham cast a line on the loch, with nil results except for the fish that ate Iain’s worms!

The peak was a delight, shapely and steep from here, with a tremen¬dous reward in the summit view over a land of water, for such is the impression of North Uist from the top.

The evening became one of marvellous calm, and a soft gold bathed yellow seaweed and grey rocks when we got back to the boat.

We boiled up some mussels, and ate them on deck while enjoying the brilliance of a sunset lighting the clouds from west right across to the east

Hardly a ripple stirred, and it was after 11 p.m. before Iain began rummaging for tins to open for our main meal, a time I was beginning to regard as normal.

For me it was my last night aboard, and virtually the end of the yacht trip, for I was due to catch Macbrayne’s boat from Lochmaddy at mid-day, and Graham was already hauling the anchor when I awoke. There was nothing to see. Mist swirled round us and even near shorelines were dim.

At 2 p.m., I stepped ashore as the mist was lifting in Uig, and as I made for my car who should be walking straight towards me but the kilted figure of Seton Gordon.

“I sent you a postcard,” he said as he shook my hand. “I saw a little white yacht nosing against An t-Iasgair. I watched it through the long glass and saw it head for the Shiants. It was you, wasn’t it?”

He listened keenly as I told him about our trip. Then we saw we were being stalked by photographers. One was John Murray of the Royal Scottish Museum, a noted eagle man, whose hero is Seton Gordon. Andrew Currie of the Nature Conservancy, and another officer of that body were there, and many snaps were taken.

Seton Gordon seemed to be enjoying himself, and his wife was laughing merrily at all the goings on. I left them heading for the boat.

My own programme was to drive down to Sleat to visit the Gaelic College. I will be reporting on the progress of the College in my article next month.

You can read the next article from Tom’s Archives on Friday, July 31.

Tom’s 1975 Archives