Tom Weir | In Rob Roy Country

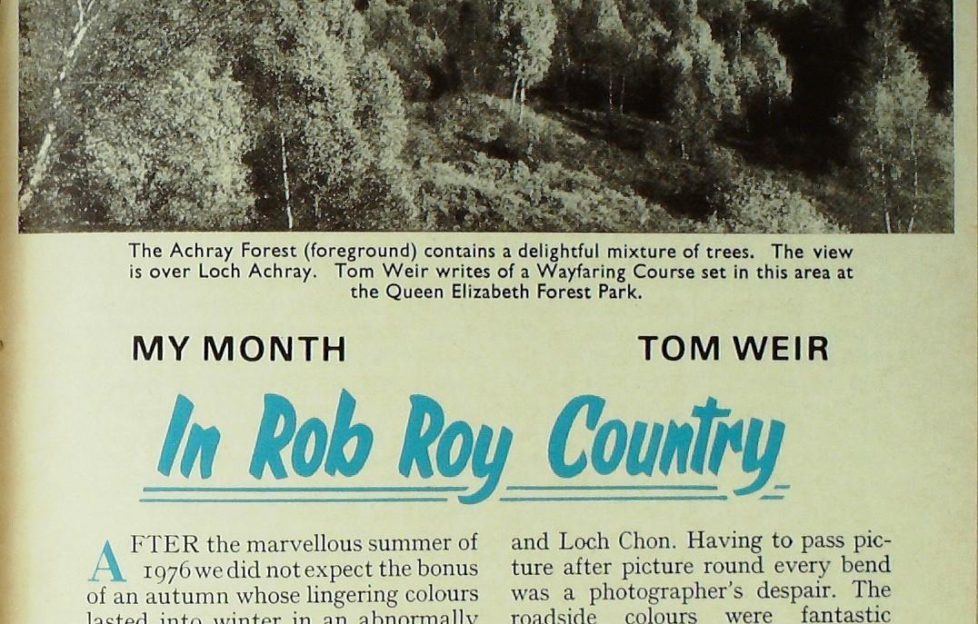

Tom Weir visited the reservoir that supplied Glasgow with 90,000,000 gallons of water a day in 1976, and opened a Wayfaring Course set in this area at the Queen Elizabeth Forest Park

AFTER the marvellous summer of 1976 we did not expect the bonus of an autumn whose lingering colours lasted into winter in an abnormally windless October and November.

One frosty morning was especially memorable, the golden ball of the sun rising into a cloudless sky glittering on the foreground rime and setting off the red bracken colours so sharply that I felt as if I was seeing my own backdoor view for the first time.

Back from a walk to enjoy the exceptional visibility I quickly packed my bag with flask and piece, picked up my camera, and took the road to Loch Katrine by Loch Ard and Loch Chon.

The reflections on the oil-smooth waters were compelling

Having to pass picture after picture round every bend was a photographer’s despair. The roadside colours were fantastic enough. It was the reflections on the oil-smooth waters which were compelling: glowing carpets richer than any Persian rug in patterns of reds and yellows and coppery colours from golden birches, smoky larches, green spruces, reds of bracken and crimson deer grass.

A little grebe was diving smoothly, creating rippling concentric rings. Fieldfares were bursting from roadside trees in soft greys and rich browns. A big flock of siskins and red-polls flew above the road.

In contrast to all this was the rise to bare Loch Arklet with the rampart of the Arrochar Alps stretched across its western skyline, a knobbly mass of grey schist thrusting up so close that you would never know that Loch Lomond was trenched before them.

My destination was the other way, east for half a mile into the wee world of Stronachlachar at the edge of Loch Katrine.

I wanted to walk the two miles of oaks and birches between me and Royal Cottage, but I was brought up short almost at once by an unusual sight, a gleaming white ship not on the water, but on shore.

Standing looking at it was a man I knew, Arthur Campbell who is superintendent of the Loch Katrine waterworks for the Strathclyde Regional Council.

“No it’s not there by accident,” he said cheerfully. “The Sir Walter Scott is up on her cradle for the Board of Trade Inspectors who are expected shortly. I’m going aboard. Are you coming ?”

I didn’t need a second invitation

As we went on board, up from below came John Mowat, engineer, the mate, John Fraser, and deckhand Robin Frame.

After he had talked business with the skipper, Arthur Campbell walked down to Royal Cottage with me.

“I never expected to be put in charge of the 25,000 acres of this estate, when I came here as a plumber,” he said.

“But it’s a very happy place. There’s more social life here than in the city. The women have the Rural, the children have a club, and so do the men. There are 64 employed, and we have billiards and darts, and a game we play called ‘Summer Ice ‘ — a kind of indoor curling. They say it was brought here by the Irishmen who constructed the tunnels, and we have a league with the surrounding villages.”

I asked him what all the men did.

“Well, there’s six in the boat crew, sailing daily from Trossachs Pier to Stronachlachar in summer. Half of them work on the estate in the winter. We have fifty houses so we need a maintenance staff of joiners, plumbers, painters and an electrician. We have 9000 sheep on the hills, so we have 12 shepherds. We have hill cattle, and we do a certain amount of vermin control.”

Loch Katrine is eight miles long, one mile wide, and about half of it reaches a depth of 400 feet.

Keeping the water pure

“We don’t allow car access except at Stronachlachar and Trossachs Pier. It’s a conservation measure because the water which goes to Glasgow is so pure that it doesn’t need treatment. The estate is free for walking or cycling, but we’d risk pollution if we made it a free-for-all and opened the shore as a motor road.”

For me the charm of Loch Katrine is that it is such an exciting place for walking and cycling, and there is no better two-mile stretch than down to Royal Cottage, with its fine views across the loch to the spine of knobbly crests that block the way to Balquhidder.

On the walk you pass the aqueduct which diverts the water of Loch Arklet into Loch Katrine, whereas it would tip westwards into Loch Lomond.

From Royal Cottage, Loch Katrine gushes out by tunnel to be carried through aqueducts by gravity to Glasgow. Archie took me down to the inlet point to read the height-marker.

“It’s two feet from the brim at the moment, and at this level the 90,000,000 gallons or more we send to Glasgow draws off no more than one inch per day.

“We could go for four months without rain here, and one of the reasons why the drought didn’t affect Glasgow was because we had so much rain during the winter and spring that Loch Katrine was abnormally high when the heatwave set in.

“But we did a historic thing last summer. We actually fed some Loch Lomond water into our system, by pumping water from their pipeline into ours. The two pipelines lie close to each other at Balmore, and about 10,000,000 gallons was pumped from Loch Lomond into our Milngavie aqueduct. We also let out about five million gallons per day to Loch Achray and Loch Venachar as compensation water to feed the River Teith.

“Lochs Yenachar and Drunkie supply the main compensation water for the Teith, totalling about 50,000 gallons a day from the three sources.”

The first modern aqueduct

Glasgow was ahead of the rest of Britain by acquiring Loch Katrine and building the first modern aqueduct.

Queen Victoria performed the opening ceremony in 1859 by sailing in the Rob Roy to Royal Cottage and opening the sluice gates to send Loch Katrine water rushing by tunnel and pipelines 25 miles to Milngavie without the need for filtration.

Mounting water-demand necessitated a second aqueduct being opened thirty years later, and in all Loch Katrine has been raised three times to enable Glasgow to cream off 17 feet of reservoir. Arthur Campbell’s main task is to control the amount of water going to Glasgow.

Driving back along the road, we stopped to look at the Factor’s Isle, now embanked against erosion by the artificial level of the loch.

This is where Graham of Killearn, Factor to Montrose was marooned by Rob Roy after being relieved of the £3000 he was carrying in rent. Meanwhile, the bold Rob was awaiting a reply to a letter he had sent to the Duke, demanding a ransom of 3400 merks.

No reply came, so Rob kept the cash he had in hand and released the furious Factor after five or six days.

Blood-thirsty ancestry

Rob was born at the head of Loch Katrine, at Glengyle, and the modern mansion on the site incorporates a lintel of the original MacGregor homestead. Above the house is the ancient graveyard of the Dugald Ciar Mhor sept of the “nameless clan.”

Blood-thirsty Dugald was Rob Roy’s ancestor, and is remembered in history for a dastardly act at the Battle of Glenfruin. Placed on guard over a party of young students who had come to watch the fight, Dugald murdered them.

The year was 1603. Between two and three hundred Colquhouns had been slain in the battle, and James VI took action by ordering that all members of the MacGregor clan be hunted down and exterminated.

Rob himself was not a bloodthirsty man. Leader of the infamous “Highland Watch ” he used his brains rather than his noted skill with the claymore.

He would take your money and guarantee to drive your cattle safely to market. If you didn’t pay, the cattle would mysteriously vanish. He was not all rogue. In these wild times of the late 17th century and into the 18th he was a force for keeping law and order.

I was thinking about Rob as I drove back to Loch Arklet and stopped at a farm called Corriearklet halfway along the north side of the moorland shore.

It was in a house of the same name on this spot that Rob married Mary of Comar at New Year in 1693. That date is just one year after the massacre of Glencoe, and it is not generally realised that Rob Roy’s mother was a sister of Campbell of Glen Lyon who was given the luckless task of master-minding that vile deed.

This was the reason that Rob changed his name to Campbell when King William proscribed again the MacGregor clan shortly after the massacre.

Farther west of Corriearklet at the end of the loch are Inversnaid Cottages where Rob had his house when he was master of Craig Rostan and had made the whole eastern shore of Loch Lomond his own.

It was here he made his greatest blunder. Fleeing north from the law he should have taken his wife and family with him. He didn’t, and Mary and her three children fell victim to constables and bailiffs under the command of Graham of Killearn.

Roughly handled and beaten, Mary was turned out into the darkness of a November night in 1712 and Inversnaid House set alight. Montrose was behind the affair. From that day he was Rob’s implacable enemy, hence the affair of the Factor’s Island which came later.

So the “Glengyle Watch” had a new role, to wage war on Montrose, which they did with such effect that a “Garrison” was built at Inversnaid so that troops could be stationed to contain Rob and his men.

I visited the ruins at dusk and had a chuckle to myself when I thought of Rob waiting until the building was nearly completed, when he swooped down, blew it up, set fire to the bunk beds and made off. Today the old walls are used as a sheep fank, and the Loch Katrine children attend the wee school next door.

The first “Wayfarer”

Just a fortnight later I was back in Rob’s country, in Aberfoyle this time, with a surprise of sunshine as I drove out of mist on the low ground into blue skies and the blazing autumn colours still continuing.

My port of call was the David Marshall Lodge to report myself ready to do my duty by performing an official opening ceremony in the Loch Achray Forest. The occasion was the starting of the new “Wayfaring Course” and I had the honour of being the first “Wayfarer.”

It was nice to see so many faces known to me, my old friend Pat Sandeman the ornithologist, Bill Murray, with whom I have explored in the Himalayas, Mrs Jean Balfour of the Countryside Commission, Bill McMurtrie of the Border Hillwalkers, and many another.

My pleasant task was to plot my way to a control point, and be the first to receive acertificate. Basically, the idea is to test yourself with a map among a maze of paths by finding your own way through the forest. Sponsors of the scheme are the Forestry Commission and the British Orienteering Federation.

“Wayfaring” is a simpler sport than orienteering in that you can make it as easy or as difficult as you like. The starting point is one mile past the David Marshall Lodge, and you need a Wayfaring Pack available at the Lodge for 3op. For this money, you get a map, a control card and instructions on how to use the course.

The starting point is signposted, and there you will find the master map showing all the control points. It is up to you to select an easy, an intermediate, or a difficult course.

Having taken your pick, you must copy the control points from the master map on to your own map the one you got in the Wayfaring Pack.

Now you can set off reading your way from one control point to the next.

In my view it is an excellent way to get some excitement from forest trails which in themselves tend to be dull because one path through dense forest tends to be very much like another.

With observation and the map you can have a lot of fun sorting out the maze of paths. You also qualify for a certificate even if you only navigate from one point to another.

Lessons from nature

Actually, the finest way of seeing the Achray Forest is to go to the top of the Duke’s Pass. Just over the crest you will find a car park with steps leading uphill from it to a scenic viewpoint. From there you can appreciate how nature and man have managed to mix natural oaks and birches with Sitka spruce and larch.

Nature has taught the forester lessons by blowing down geometrical blocks and forcing him to replant with more ragged edges. The result you can see before you in trees of various ages and species giving great richness of colour and variety.

Today, there are something like 170 miles of paths in the Queen Elizabeth Forest Park, and even Rob Roy, whose map was in his head, could get lost here.

My own feeling is that in my lifetime this side of the Trossachs has been beautified immensely since it became a State Forest 40 years ago. It holds an infinitely greater wealth of wild life than in the old days.

As for Loch Katrine, I think we could call it our first real Nature Reserve, thanks to water conservation and the necessity of keeping it free of pollution.

Anyone can enjoy Loch Katrine, but to explore its shores and glens you must pay a capital price of foot-poundage, or push a bicycle. The balance between access and inaccessibility is nicely held, benefiting us all.

Footnote for long-distance walkers: the bridge at Cuilness on the path between Rowardennan and Inversnaid has now been replaced and removes the danger from this fine walk in time of flood. The Forestry Commission carried out the work during November.

West Highland Way walkers should take account of the fact that there is no footbridge across the Ben Glas Burn. The one shown on the map was swept away by the same flash flood which swept away the Cuilness Bridge two summers ago.

In Tom Weir’s next update from February 1977 (going live on Friday, August 21) read about his spring expedition to Loch Nevis with Jeremy J. C. Fenton.

1975 Archives

1976 Archives

- More instalments every Friday