Tom Weir | West Highland Magic Part 4

Tom Weir’s feature on discovering a “passport to wonder” through the West Highland Railway line, republished from a 1960s issue of The Scots Magazine

Click here for part one

Click here for part two

Click here for part three

In the mile that separated me from Bridge of Orchy and the train I was soaked to the skin again, and had to ring out my clothing in the lavatory, steaming steadily all the way back to Glasgow.

Little could I have foreseen the social change that each of these constructional jobs was to bring, as tunnels and pipes were driven through from Loch Treig to sprout out of Ben Nevis and provide power for aluminium production.

Industrial expansion swelled the population of Fort William, and with it resulted an increased rail freight and passenger traffic—for a time.

Then followed a slow wind of change as petrol rationing came off and an age of full employment packed the roads with motor cars, while lorries competed with the railways for freight.

I need look no further than my own history. Since 1950 I have used the West Highland Line only three times, twice on day outings to ski on the Corrour Hills, which cannot be reached by any road, and the third time in September last when I went to Mallaig to talk to some of the men who operate the line and learn what is happening to the railway.

John Fraser, the travelling ticket collector, was quick to take me up when I referred to Mallaig as being on the West Highland Line.

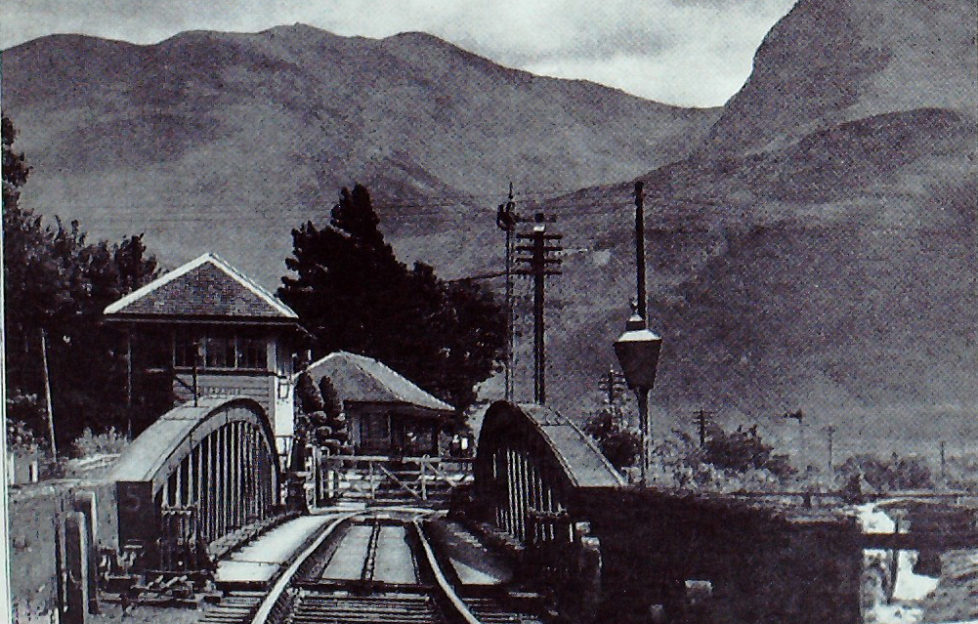

To him it was still part of the “Mallaig extension,” opened in 1901 after delays due to tunnelling and blasting, cutting and levelling.

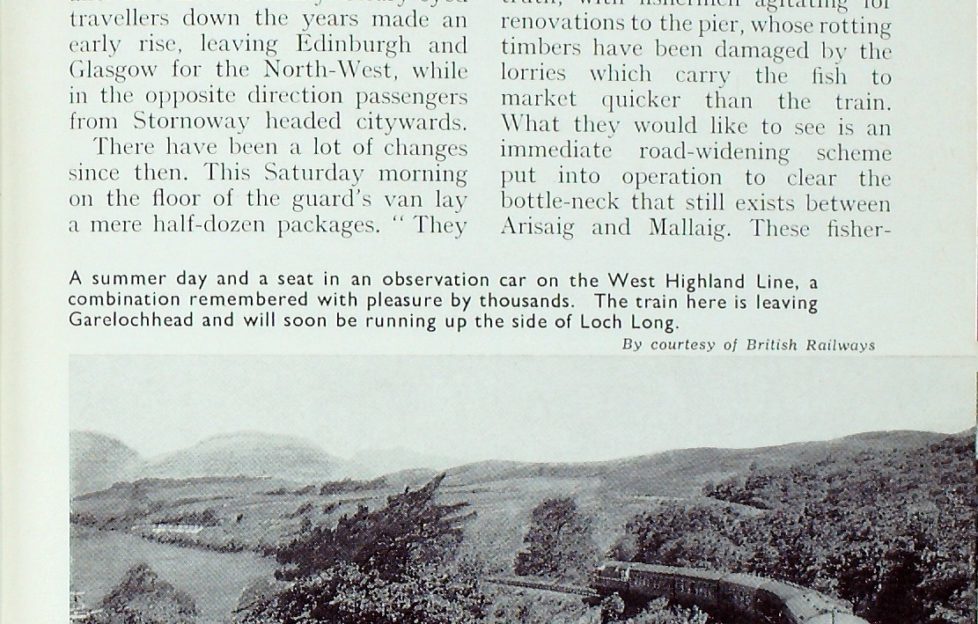

Then came the great day of April 1, 1901, and the first of many bleary-eyed travellers down the years made an early rise, leaving Edinburgh and Glasgow for the North-West, while in the opposite direction passengers from Stornoway headed citywards.

There have been a lot of changes since then.

This Saturday morning on the floor of the guard’s van lay a mere half-dozen packages.

“They put up the rate in August, and that’s the result,” a man said to me. ” It’s cheaper now to send a parcel by post, let alone by road.”

“What about the fish traffic?” I asked.

“Fish! What fish? The fish go in big lorries now. The summer time-table is the only thing that brings a stir to this line now. And when the tourists are gone it’s finished.”

In Mallaig I found he spoke the truth, with fishermen agitating for renovations to the pier, whose rotting timbers have been damaged by the lorries which carry the fish to market quicker than the train.

What they would like to see is an immediate road-widening scheme put into operation to clear the bottle-neck that still exists between Arisaig and Mallaig.

These fishermen are convinced that the railway had outlived its usefulness, though they were prepared to admit its convenience in time of snow, as happened two winters ago when all roads south were blocked, but the trains were running to time.

Yet Mallaig owes it present pier and breakwater to the railway, the Government of the time contributing £30,000 towards its cost in the hope that crofting and fishing would benefit.

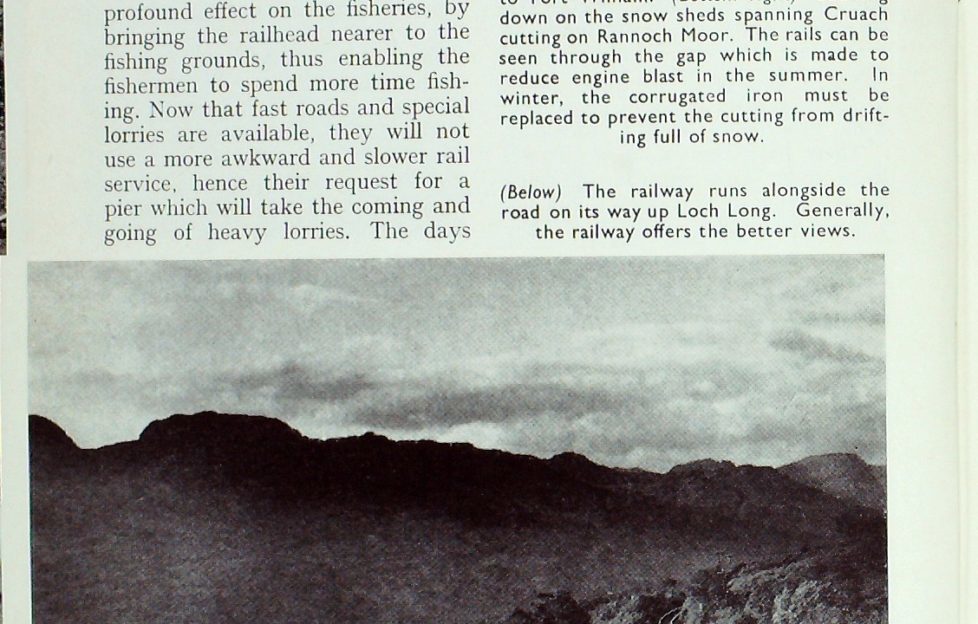

The railways did have a profound effect on the fisheries, by bringing the railhead nearer to the fishing grounds, thus enabling the fishermen to spend more time fishing.

Now that fast roads and special lorries are available, they will not use a more awkward and slower rail service, hence their request for a pier which will take the coming and going of heavy lorries.

The days of fish trains, it seems, are over.

Read the next excerpt from Tom Weir’s

“West Highland Magic” online next Friday!

- Zoom-in for carousel. Scots Mag copyright.