Tom Weir | My Loch Lomond

Few men can know Loch Lomond as intimately as Tom Weir who lived by its shores for 17 years. In his columns for our July and August, 1976 issues he paid tribute to it in words and pictures…

SUNDAY morning in Gartocharn where I live, and I am up early to enjoy a few hours on the marshes of Endrick Mouth before the world is awake.

This is a time when I don’t want company, but like to let my mind dwell only on the sights and sounds of the Loch Lomond shore.

Each day has its own mood. This one has vigorous clarity. The crags of nearby Conic Hill are grey. The heather is richly warm. Yellow water lilies float with pink persicaria in the pools. The white blocks of quartz near the top of Ben Lomond sparkle like snow, and cloud shadows float across the knobbly peaks of the Arrochar Alps.

It is not so much a walk I am taking as a series of stops, to enjoy the little things that tell how the breeding time-clock is ticking: mergansers with big flotillas of fluffy youngsters, the plumper shelduck which nest in rabbit holes. The vividly black-white-and-red adults are swimming about with bundles of striped young. Alarmed, a dozen of the youngsters try to keep up with mother, who puts on a spurt.

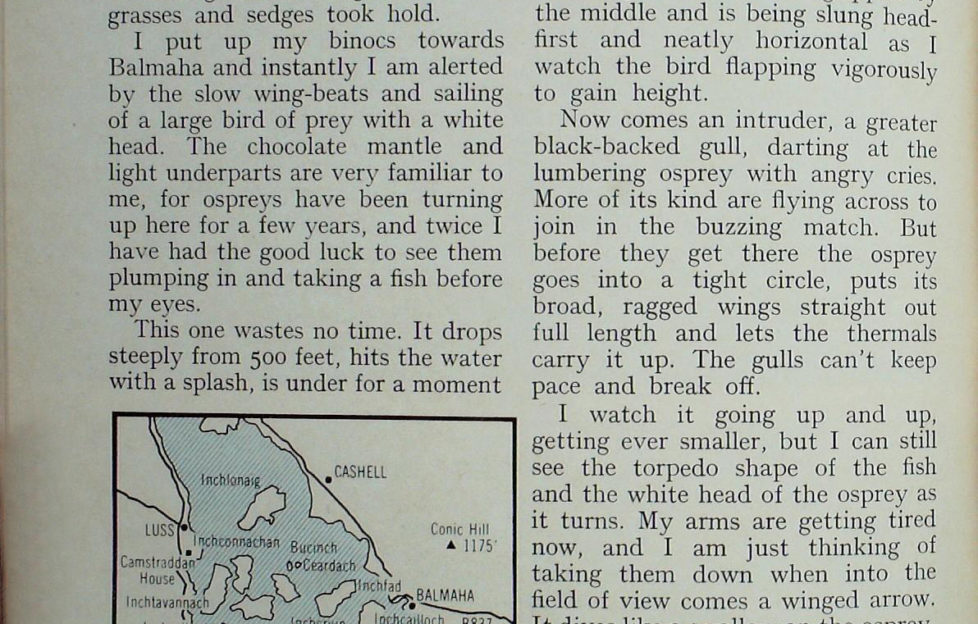

I am on a narrowing strip of land of shallow lagoons which ends at the Ring Point where the River Endrick discharges into the loch. These lagoons are former mouths of the Endrick, before the river was pushed back by ridges of sand thrown up in winter storms over the past 200 years or so.

Now there is thin vegetation, thanks to a unique community of plants, one of them a waterwort with a pinkish flower, discovered only in 1968. This plant, with another annual, Peplis portula, together with the perennial Eleocharis acicularis, was the means of stabilising the shifting sand while grasses and sedges took hold.

Aerial acrobatics

I put up my binocs towards Balmaha and instantly I am alerted by the slow wing-beats and sailing of a large bird of prey with a white head. The chocolate mantle and light underparts are very familiar to me, for ospreys have been turning up here for a few years, and twice I have had the good luck to see them plumping in and taking a fish before my eyes.

This one wastes no time. It drops steeply from 500 feet, hits the water with a splash, is under for a moment but seems to be having some trouble rising, bashing its wings on the water several times to lift off hoisting a hanging fish that appears to be hooked by one talon. The osprey seems to be off balance, and with an awkward swerve drops back into the water and goes under with the fish.

It reappears, seems to be swimming for a moment, then after a few slaps with its wings on the water up it goes, and this time the big fish—a pike I think—is gripped by the middle and is being slung head-first and neatly horizontal as I watch the bird flapping vigorously to gain height.

Now comes an intruder, a greater black-backed gull, darting at the lumbering osprey with angry cries. More of its kind are flying across to join in the buzzing match. But before they get there the osprey goes into a tight circle, puts its broad, ragged wings straight out full length and lets the thermals carry it up. The gulls can’t keep pace and break off.

I watch it going up and up, getting ever smaller, but I can still see the torpedo shape of the fish and the white head of the osprey as it turns. My arms are getting tired now, and I am just thinking of taking them down when into the field of view comes a winged arrow. It dives like a swallow on the osprey, misses as if by inches, shoots back above the osprey as if gravity was nothing, and swoops again and again.

Only a peregrine could put up such a display. Compared to the dot of the falcon, the osprey is an aerial comma in the sky. The birds are so high now my neck is getting sore, but the attack goes on for minutes yet. I hold it long enough to see the falcon break off the engagement. Somewhere the osprey will be coming down to eat its well-deserved fish — if it still has it.

Childhood encounters

I find myself thinking now about my old pal Matt, whose face and eyes would have been alight with pleasure at the sight of such an encounter. Matt died eight years ago, but he is still my invisible companion. We were loners, teenagers, when we met for the first time on a West Highland train going north up Loch Lomondside, discovering that we shared the same breed of hobby-horse, a tandem— hills and rock-climbing in the front seat, and a deep curiosity for wildlife pedalling in unison behind.

It was Matt who found the newly-hatched ring plovers shown in the colour photograph on page 397. Little did we know as I took the photograph and showed it later at a meeting of the Scottish Ornithologists’ Club in Glasgow that it was the first proof of the breeding of this species on Loch Lomondside.

In those days of the early 50’s, bird-watching and record-keeping was not the highly organised thing it is now. At the time we did not know how lucky we were to be discovering the Endrick for ourselves as an exceptional place for bird migration. It was a joyful time recording so much that was new and unexpected ; the hosts of waders which could arrive from their Arctic breeding grounds when a dry summer shrank the loch and provided sandbanks and a generous shoreline for feeding.

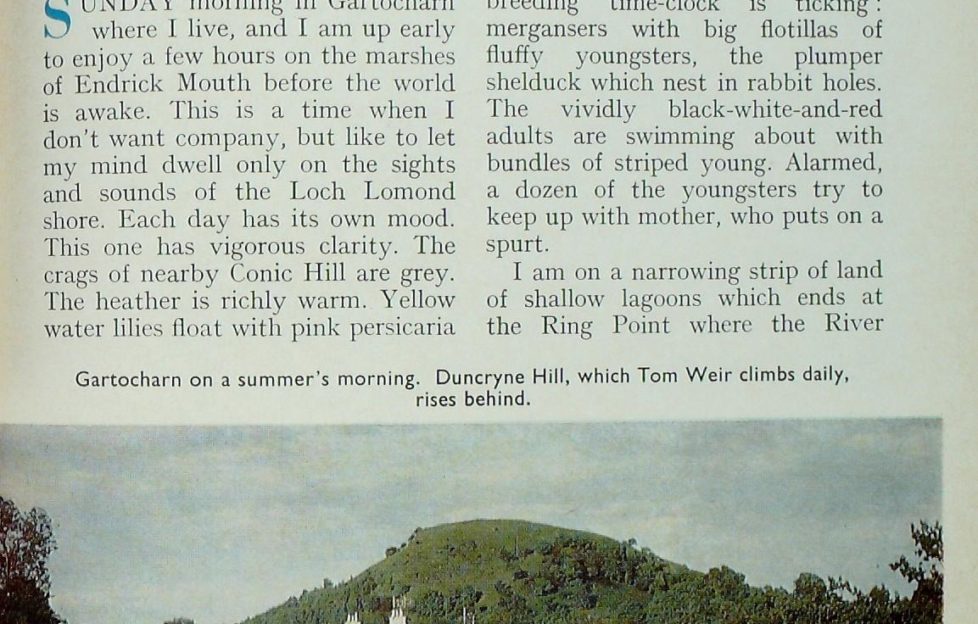

It was against this background I chose the village of Gartocharn on the southern shore of the loch as a permanent home 17 years ago when I moved from Glasgow. There was another attraction for me, a small hill called Duncryne, at 462 feet, the perfect size for climbing every morning before starting work. Small as it is, I am aware that I shall never know all the secrets of this “crag- and-tail,” whose volcanic mass was shaped by the bulldozing away of the softer rocks around it when the glaciers from the North dug the trench now occupied by Loch Lomond. Standing on the edge of the Highlands, Duncryne looks down on a meeting of valleys from which rise the other volcanic necks of the Campsies and the escarpments of the Kilpatricks, the Ochils, the Renfrewshire hills and the seaward ridges of Cowal.

“Nowhere else known to me is so magical in spring”

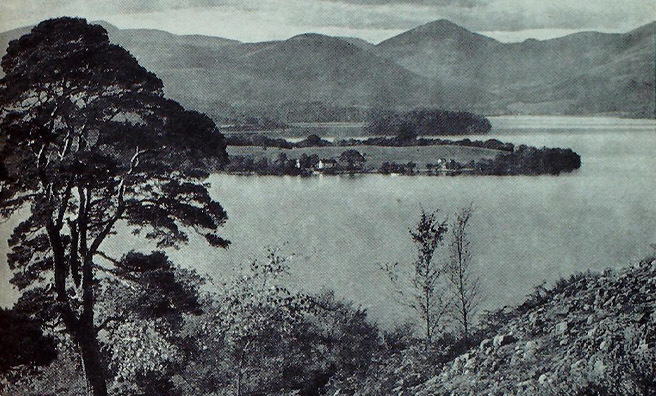

No camera can do justice to the peak upon peak which forms the whole northern horizon above the mirror to the sky that is the broad base of the loch, nearly five miles across, but saved from monotony by its archipelago of wooded islands. Every day and every hour can produce a different mood. Nowhere else known to me is so magical in spring, when the blackthorn froths and the yellow primroses are swamped in the bluebell seas as oaks burst into yellow leaf against the silky greenery of beech and birch, larch and ash.

Inchcailloch—the Island of the Old Women—is a good place to enjoy it all, only a minute across the short strait from Balmaha on the exact line of the Highland Boundary Fault. Walk through its central valley and climb to its crest 250 feet above the loch and you have a perfect summary of the contrasts of a loch that is both Highland and Lowland.

The word ” inch ” comes from the Gaelic ” innis,” an island. The old women referred to in Inchcailloch were probably followers of St Iventi- gerna, mother of St Fillan and daughter of the King of Leinster who retired to this Loch Lomond island at the end of her life and died here in A.D. 763. This island, together with its neighbours Clairinch, Torrinch, Creinch, Aber Isle, and the marshes south of the Endrick, became a National Nature Reserve in 1962.

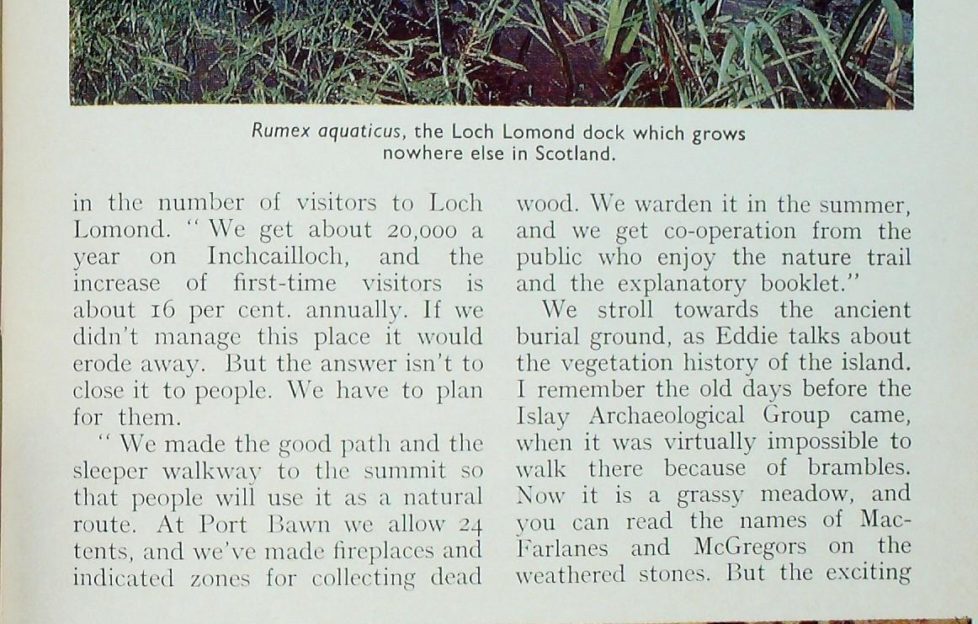

The warden/naturalist who was appointed to take charge was Eddie Idle, who, after 14 years, is being moved to a new region. Eddie has been a special friend all this time. A botanist by training, his was the thrill of discovering the little waterwort which helps bind the sands of the King Point. He has written papers on Rumex aquaticus, the Loch Lomond dock which grows only here in Scotland. Before lie left to take up his new post we had a walk on Inchcailloch to look at its oak woods.

Here is thrilling material for a botanist, a semi-natural forest un-grazed by domestic animals, where nature has acted as forester, with an exceptionally high density of birds including pied flycatchers and two kinds of woodpeckers, green and greater-spotted. We take the nature trail through the sheltered valley which leads to Port Bawn at the far end in less than a mile. Above us a sleeper walkway climbs the rocky crest to the 250 ft. summit. ” I carried some of these sleepers,” he grins, ” and it was heavy work, I can tell vou.”

Eddie, in his 14 years here, has seen at first hand the continual rise in the number of visitors to Loch Lomond.

“We get about 20,000 a year on Inchcailloch, and the increase of first-time visitors is about 16 per cent, annually. If we didn’t manage this place it would erode away. But the answer isn’t to close it to people. We have to plan for them.

“We made the good path and the sleeper walkway to the summit so that people will use it as a natural route. At Port Bawn we allow 24 tents, and we’ve made fireplaces and indicated zones for collecting dead wood. We warden it in the summer, and we get co-operation from the public who enjoy the nature trail and the explanatory booklet.”

We stroll towards the ancient burial ground, as Eddie talks about the vegetation history of the island. I remember the old days before the Islay Archaeological Group came, when it was virtually impossible to walk there because of brambles. Now it is a grassy meadow, and you can read the names of MacFarlanes and McGregors on the weathered stones. But the exciting thing is the church foundation, 64 feet by 19 feet, and the collection of carved bits of it excavated by the diggers. The church dates to 1225 or earlier, and was built to honour St Kentigerna 300 years after her death. It remained the Parish church for the next 500 years.

During these early days in the written history of Inchcailloch the monks of Paisley Abbey shared with local kirks the right to exploit the Loch Lomond woods. There was also the Dumbarton shipbuilding industry using this source of timber in the 15th century. A century later we hear of Inchcailloch being farmed. The ruins are at its north-western end.

Eddie explained the present semi-natural oakwoods by telling me their history from the farming time on the island.

“Probably the woodlands were pretty well cleared. Then, when there was a demand for oak bark for tanning, the island was replanted and the trees coppiced at about 24 years old to make new shoots grow from the stump. The forest around us now dates from the abandonment of the bark industry in the 19th century.”

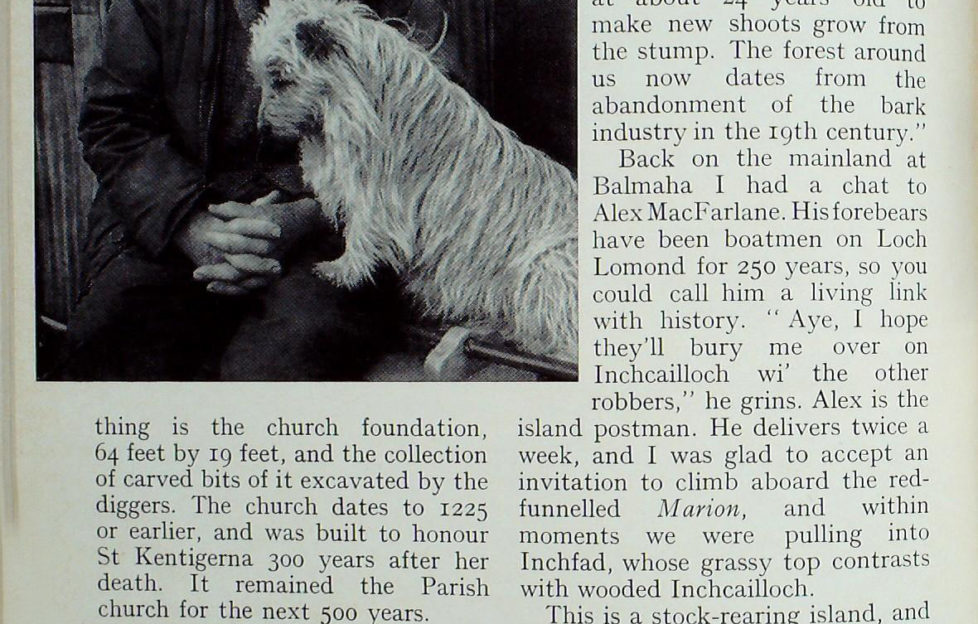

Back on the mainland at Balmaha I had a chat to Alex MacFarlane. His forebears have been boatmen on Loch Lomond for 250 years, so you could call him a living link with history.

“Aye, I hope they’ll bury me over on Inchcailloch wi’ the other robbers,” he grins.

Alex is the island postman. He delivers twice a week, and I was glad to accept an invitation to climb aboard the red- funnelled Marion, and within moments we were pulling into Inchfad, whose grassy top contrasts with wooded Inchcailloch.

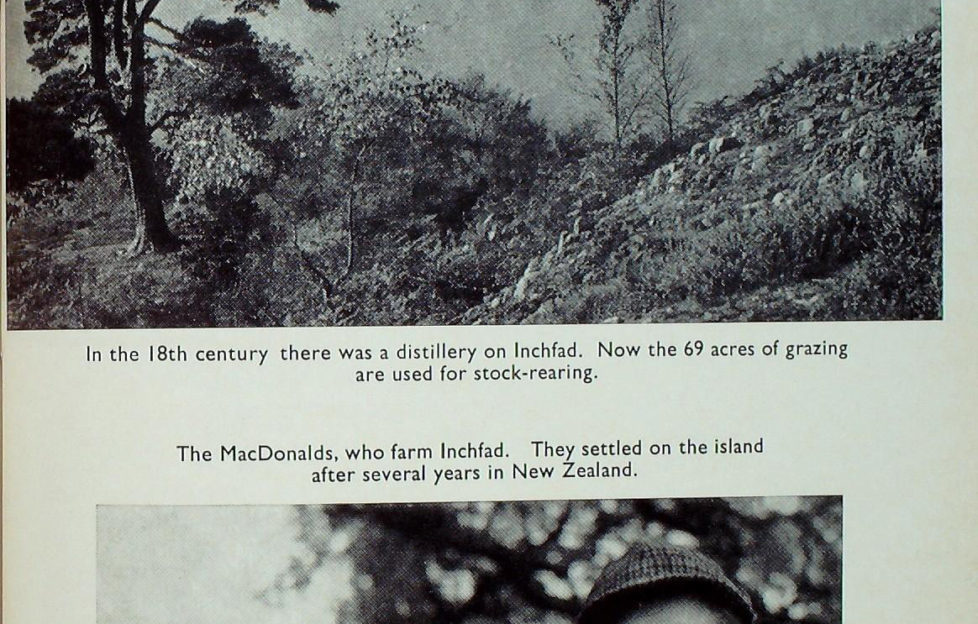

This is a stock-rearing island, and Mr MacDonald, who farms it, hails from Glenuig, near Mallaig. though he was in New Zealand before coming here a dozen years ago. His grazing land is 69 acres, the remainder of the small island being wooded. I asked his wife how she liked having an island to herself, and she told me she loves it.

Alex adds a titbit or two as we sail away.

” In my great-grandfather’s time, aboot 1783, he had a distillery on Inchfad. Duncan, his son, was a shoemaker, and the Excise appointed him to collect the whisky tax at Balmaha before the spirit was sent across the loch and doon the Leven by boat.

” My own grandfather carried wood from Loch Lomond tae the Paisley mills—birchwood used in the making of bobbins for thread. He filled up again wi’ coal on the other side, and got pulled up the Leven wi’ trace horses.

As Alex was speaking, we were steering west for Inchmurrin, the biggest island, one time stronghold of Duncan, Earl of Lennox, who was executed by James I and his male heirs exiled or imprisoned. Passing the ruins of ivy-clad Lennox Castle, I thought of Duncan’s widow, who was allowed to remain, and who spent the remainder of her life in charitable works.

Soon we were pulling into Tom Scott’s jetty. Tom is a farmer who enjoys the whole business of rearing livestock and selling it, but could hardly survive the difficult financial times if it weren’t for the tourists who come over to water-ski or have a meal at his hotel. A successful heavy-weight athlete in his day, and keen outdoor man, he has spent most of his life on Inchmurrin.

” Sometimes I get fed up and think I’d like to make a move. But it’s a good place. I’ll stick it out.” Boat- hirers from Duck Bay and Balloch serve Inchmurrin.

Leaving the island, we struck north, to pass close to the parklands of Rossdhu and the big house of the Colquliouns, which now opens its doors to the public. Sir Ivor, the present laird, lives at Camstraddan near Luss. In my mind’s eye, I could see the face of a disapproving Colquhoun, the famous sportsman/ naturalist of the family who, as long ago as 1849, was deploring the erosion of the Highlands by exploitation.

It was this John Colquhoun who destroyed the Loch Lomond ospreys which for centuries nested 011 the Castle of Inchgalbraith, just northeast of Rossdhu, an action he was to regret in later life. He would be nodding with approval at the return of the birds, even if they have not yet built a nest and raised chicks so far as we know.

Inchtavannach lies less than a mile north of Rossdhu, wooded and shaped like a bowler hat at its northern end. Only one family lives on it. The husband is television director Brian Mahoney, who commutes to Cowcaddens in Glasgow most days. He reckons the inconvenience of having to man a boat to get to his car is worth it for the pleasure of living on such an island.

“My wife took to it like a duck,” he tells me. “She’s known as ‘the Lady of the Lake!’ Over 20 years’ working in television I’ve learnt a number of skills, like working with engines and using a power saw. We keep two goats and a dozen ewes. I like to think I’m giving my two children the chance to learn independence. Living on an island is a highly personal experience, when you are the only family. It’s a real world, quite different from my work in television.”

Tom Weir continued his portrait of Loch Lomond in the next issue (August, 1976) – republished here!

More from 1975

More from 1976

- July 1976: My Loch Lomond

More instalments every Friday