Tom Weir | Memorable Days

Mountains are great for cutting you down to size whatever your experience

Len and I thought we knew everything that the Buachaille Etive Mòr can produce, but our old friend of innumerable ascents had a surprise in store for us on a bleak cloudy day when the air was full of damp as we donned our boots.

We had been trying to arrange this climb for quite a while. Len had been out of action due to leg trouble and it was two years since we had been linked by the rope.

He had been telling me how much he had been missing rock climbing and the zest for living you feel at the end of a hard day.

Right now our arrangement did not look quite so attractive as we slung our sacks and set off up the north-east face as we have done on many other ascents.

Len wrote the two-volume SMC Climbers’ Guide to Glencoe, so has a unique knowledge of these crags.

As yet we hadn’t discussed what we might climb. We simply kept going until we found steepening chutes of grey-pink stones becoming rock and struck up until we found ourselves in Crowberry Gully.

A sharp exit on its left wall and we were soon at the foot of its retaining ridge which is one of the great classics of Scottish Mountaineering.

It was climbed direct for the first time in 1900, four years after its very first ascent by its easiest route.

The Summer We Didn’t Have

Normally we scramble up to Abraham’s Ledge without the rope, but we found the introductory cleft so awkwardly slippery that we were glad to rope up for the next 60 ft. pitch where I made full use of the excellent handgrips.

My feet were slipping on holds that felt as if they had been soaped and I would have been glad of the friction of old-fashioned tricouni nails.

Len’s rubber soles were doing the same.

“I’ve never known these rocks so greasy,” he said. “It must be the result of the summer we didn’t have.”

He surprised me however by not taking the line of least resistance but setting off on Greig’s Ledge which has a very awkward and exposed move.

I was not sorry when its slippy surface persuaded him to take the easier and lower detour of the original route, though even it required exceptional care, it was so slimy.

Back on the airy crest I took over the lead again hoping for better things on cleaner rock. This section is steep and pleasant as a rule, but not that day.

At the end of my rope I came on a young climber belayed on the only ledge watching his leader trying to make a turning movement round an edge which would take him out of sight of us.

He made it just as Len joined me, but there seemed to be something holding him up beyond and all of us on the ledge were getting very cold.

Just as the leader was running out of rope he shouted that he had found a stance.

“Come on!” he called to his second—easier said than done for the youngster hadn’t a clue how to tackle the problem. After he had swung of on the rope three times he shouted up that he wasn’t going to make it.

“You’ll have to,” came the not very reassuring answer. “You’ve got to get up.”

Len and I had been quietly discussing an alternative route out to the right. He set off on it, while I took the worried climber in hand.

“There are some holds there that you’re not using. Now if you do what I tell you you’ll get up all right. Don’t hurry your movements. Place your feet, keep your balance and try to keep moving.”

He nodded and then by way of explanation added, “I’ve never climbed before today.”

He did well, placing his feet as I had suggested, and while he was moving Len had gone right and was above him ready to give a hand if he needed it.

But he got over the bulge which was the crucial bit, and in two more rope-lengths we were all up, passing a third party on the ridge so that we had the delightful crest of the Crowberry Tower to ourselves, even if it was only a point in space with no horizon.

“The mountain had worked its magic.”

Now we were in great spirits. Even if the ascent had not been “enjoyable ” because of the grease, the concentration required had worked its magic. As we went back down by the Curved Ridge we felt we had had a great day.

My next day on a mountain was with Pat when we went deer-stalking, not with the rifle but with binoculars, to look down on rutting stags with their hinds in a wide corrie full of angry roars, deep-throated and menacing.

The joy of that day was its crystal brilliance—pale blue sky, the hills rich brown, grey rocks sparkling, and the red deer catching the light as antler-tossing stags in possession of hinds chased off rival intruders.

We saw no actual fights, for the rivals usually turned tail and raced away with the powerful master stag in pursuit but never going far in case some of his hinds might be poached by another opportunist stag.

And while we watched the annual courtship spectacle, five ravens were croaking and tumbling overhead as if in anticipation of spring.

How lovely it was descending from the heights by the burn-side in the late afternoon, on a path winding above silver birches and rowans tinged with the gold of the setting sun.

And a further pleasure was added when the shepherd turned out to be an old acquaintance from Glen Lyon who invited us in for tea and a chat with his wife about the days of 40 years ago when, with other shepherds, he used to walk the sheep over the drove road from Innerwick to Loch Rannoch, and on by tracks to Loch Garry for Dalnaspidal to load them into the train for wintering on the Moray Firth.

Deeside At Its Best

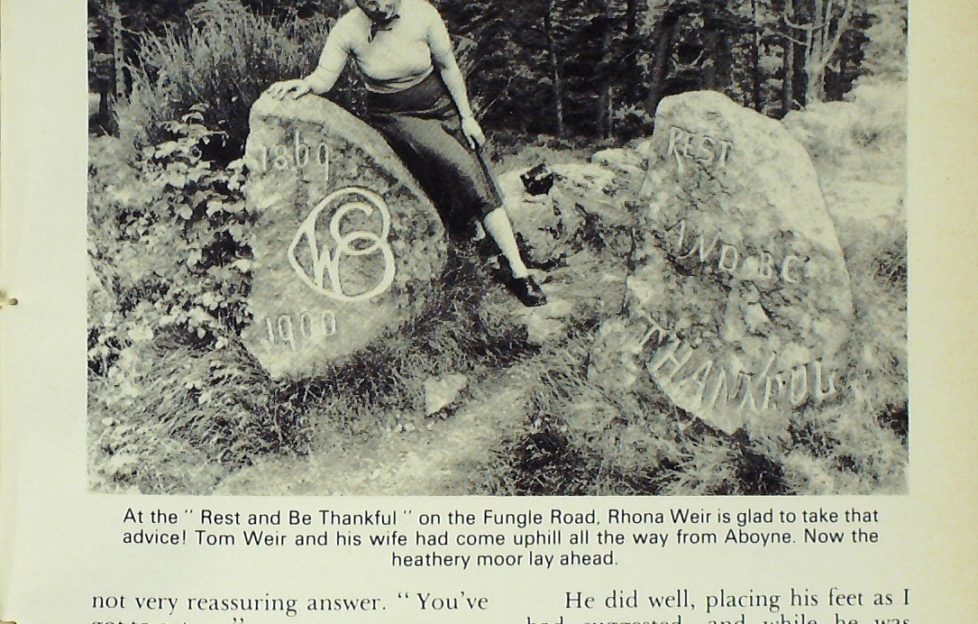

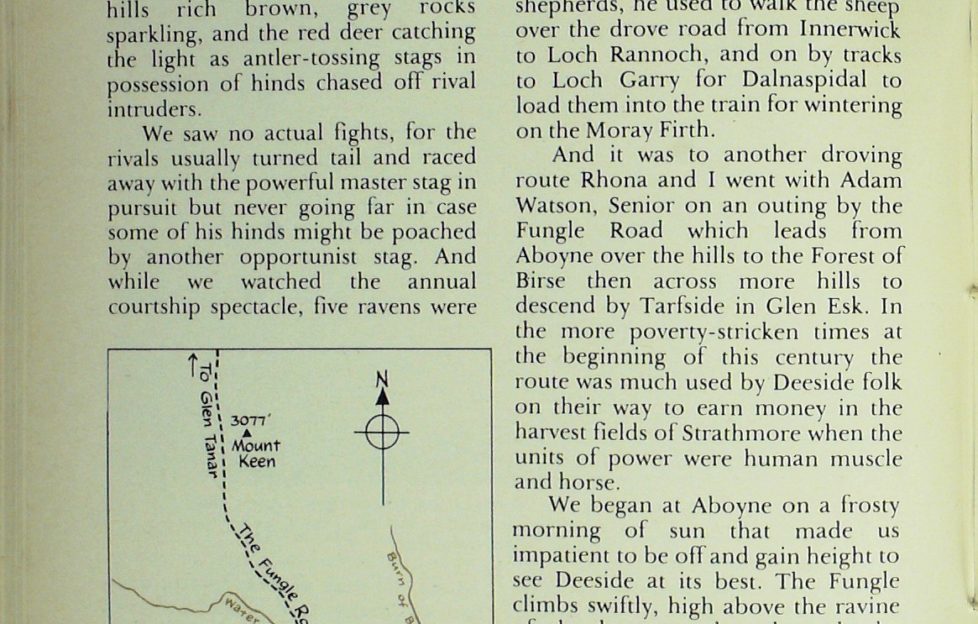

And it was to another droving route Rhona and I went with Adam Watson, Senior on an outing by the Fungle Road which leads from Aboyne over the hills to the Forest of Birse then across more hills to descend by Tarfside in Glen Esk.

In the more poverty-stricken times at the beginning of this century the route was much used by Deeside folk on their way to earn money in the harvest fields of Strathmore when the units of power were human muscle and horse.

We began at Aboyne on a frosty morning of sun that made us impatient to be off and gain height to see Deeside at its best.

The Fungle climbs swiftly, high above the ravine of the burn so that through the wooded jaws of the pass you look down on the white dots of the village.

Behind it rises a green quilt of fields reaching up the high forest and heather, with on the left the white tower of Aboyne Castle guarding the old crossing of the Dee and access to the pass.

Everything about this countryside is imprinted by man and has the look of being cared for, even the beautifully inscribed “Rest and be Thankful” stones, with the exhortation: ” Oh ye mountains, Oh ye waters, Praise ye the Lord “, and where better to appreciate them than from this ledge high on the hill above the pines with the heather stretching ahead where we followed a delightful boot-width path.

Stretched out on a knoll enjoying the warm sun and exhilarating air we debated whether to go on or return to the Dee and come in by Glen Esk another day.

It seemed a good idea to retrace our steps when the lower ground was so much more colourful than usual.

And we had no sooner done an about-face when over the ridge soared a golden eagle, sailing and flapping occasionally, lingers at the end of long outstretched wings feathering the air and its head with the glint of gold as it turned.

Events were favouring the ornithologists that day for as we jogged down the steep ravine, out on the right almost level with us soared a round-winged bird with longish tail, its barred plumage and outline like a sparrow hawk but bulkier.

Even as we were exclaiming “goshawk!” it was off with a dash to head off another predator crossing its air-space, a kestrel. It went to grips with it and seemed to clash wings several times before breaking off and letting the kestrel go.

Riches enough for one morning you might think, but there was more to come later when a thrush shrieked past my nose in alarm followed by a sparrowhawk which rose over my head and zig-zagged into the trees.

We hoped the sparrowhawk had missed its lunch as we picked up the car and found a spot to enjoy the activity of redwings and fieldfares chuckling and squeaking among the trees or flying in droves of hundreds raiding the red berries.

Past Ballater we ambled on by Balmoral to the Ballochbuie woods by the Old Bridge of Dee, marvelling at the variety of this river which rises at 4000 It. as a spring on Braeriach and in such a short distance becomes a mixture of primeval wildness and sylvan beauty, nowhere more lovely than on the rise of Lochnagar.

But good days up there were few in the disastrous summer of 1979, and all along this upper Deeside road there was clear evidence of a harvest that came too late.

Before returning to Banchory for the night there was just time to climb Craigendarroch above the Pass of Ballater, a mere 1250 ft. but a splendid round by the path threading the oakwoods and dills to the heathery top. From up there we looked down on the derelict railway terminus, and what used to be the line to Aberdeen, part of which is now in use for walkers and pony trekkers.

A Natural History Master

I stayed at Banchory, not only because Adam Watson and his father live there, but because I wanted to go into Aberdeen to hear Desmond Nethersole-Thompson give one of his very infrequent lectures about his life in the Highlands spanning a period of over 40 years and culminating in such outstanding natural history books as Snow Buntings, Pine Crossbills, The Dotterel, Highland Birds, and his latest, Greenshanks, which I had the pleasure of reviewing recently in this magazine.

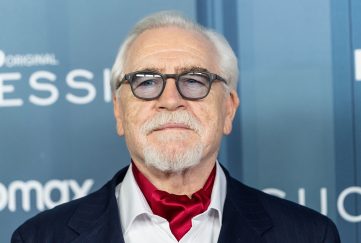

It proved to be a great evening, beginning with a sherry party in the Zoology Department of the University, and Desmond looking bland and patriarchial, white beard nodding benignly, eyes gleaming behind the spectacles.

Even at rest on a sofa he looks a big man. When he stands up, his presence is commanding.

When Desmond gave up schoolmastering and came to the Highlands in the 30s he had nothing except a determination to make a life study of the most difficult birds in Britain of which little was then known because of the immense demands made on the stamina of anyone who would seek to watch them in their bog, forest and mountain-top habitats.

Desmond lived in a shack above the Spey Valley, with no water except what came through the roof; food and fuel shortages made the winters desperate, but his notebooks filled up rapidly with unique observations.

In his talk he told us the story of his life, beginning with the great men of his youth in England, the egg collector naturalists who were founders of bird study.

To finance his own bird studies Desmond collected for them and ploughed the money into his own researches for there were few grants to be had in those days, unlike now when such work is subsidised.

He told of his political life and years in Local Government, his attempts to become a Member of Parliament, his happy years married to Carrie in Rothiemurchus.

Then of the switching from the Cairngorms to the bogs of Sutherland and the raising with Mairnie of a new family, each new member becoming one of the ornithological team.

Inspiring The Next Generation

One at least is on the way to following Dad as he studies for first class honours in biology. Maimie was there that night too, and the joyful thing about the talk was that so many young folk were there to hear at first-hand how the world has changed so drastically for good as well as ill within the lifetime of one exceptional out-door man.

I met some fine young ornithologists too, notably a trio of working lads who after last year’s hard winter set out to determine the status of the dipper on their local rivers.

They found over sixty nests, but they also discovered that because of the exceptionally high water inundating the nest sites there was insufficient time for the birds to raise more than one brood.

I asked them about grey wagtails, telling them that our birds had been pretty well knocked out by the winter but they told me that they had found over two dozen nests while doing their dipper survey—good news indeed, for this longest-tailed od the wagtails, with the canary yellow and grey, is one of my favourite birds.

With the two Adams as guides, the next jaunt was to see the gorges of the North Esk going in from the bridge on the B966

First we drove two miles up the road, then parked the car and traversed in to find a delightful path cut along the wall of the rock gorge above the swirling river, brown as beer and with a head of froth and bubbles between waterfalls.

The rock was sandstone with imbedded pebbles, hung with berried trees and squeaking with redwings and the soft calls of bullfinches.

There was a wealth of colour although the sun wasn’t shining and there was a certain gloom from the closeness of the gorge walls.

Never dull though, as below us a goosander took off twisting down-stream, and above the noise of the water we could hear the spurting song of a dipper.

We had good views, too, of its white bib as it bobbed, took off just above water level and then dived in, no doubt to walk on the bottom in defiance of the rush of water over its strange stumpy little body.

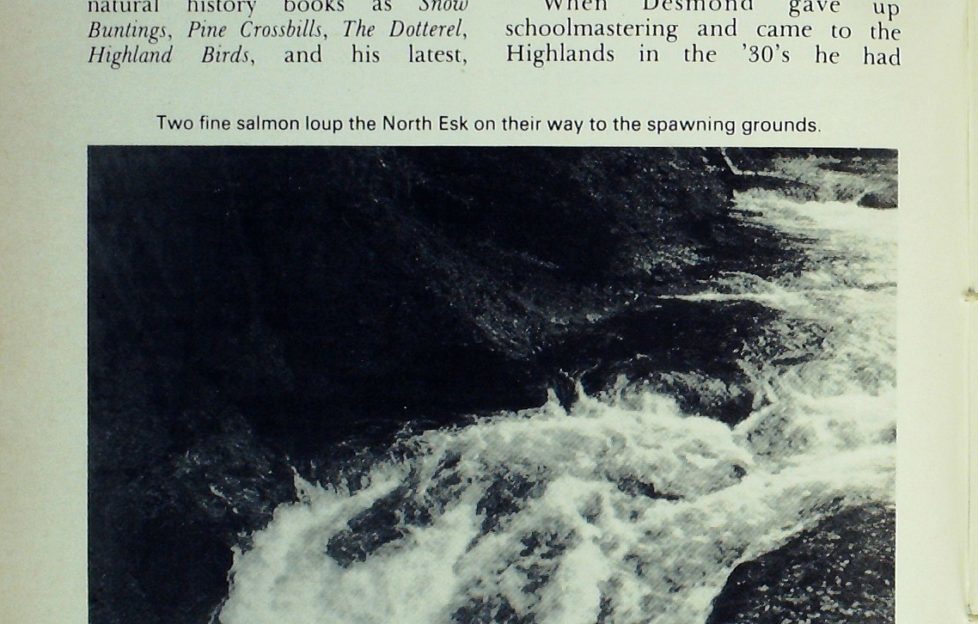

Soon we came to the salmon loups where a fish pass has been cut from the rock but was being ignored since the big fish kept hurling themselves at the main cataract.

Most were the red fish, which Adam told me are called ” kippers ” by the local folk, fish ready for spawning which are no longer good eating.

A little lower than the fall seemed to be the resting place and we could see big fish lying on rock slabs just below surface level, heads to the rush of water, tails gently fanning and fins moving to keep them steady side by side. Alas, a few had the white fungus of salmon disease on them.

Afterwards we headed up the glen to where the Fungle Road comes out at Invermark. Another route divides to cross the shoulder of Mount Keen and descend by Glen Tanar or an alternative path to Ballater.

We chose to go up past the striking castle walls of the ancient keep, now only a shell, then into an icy wind blowing down from choppy Loch Lee where the last birches had the shine of pure silver against the dark slopes of the cirque which culminates in Craig Maskelciie, sharpest and rockiest of the group.

It was so cold we were glad to shelter in the wee cemetery. There was insufficient time unfortunately to visit the Falls of Unich or stravaig up the Shank of Inchgrundle. They would be pleasant ways of getting to Glen Muick.

In contrast to the heights, I chose later to visit the Ythan and the Sands of Forvie for a “birdy walk ” from Collieston, having heard great things of vast numbers of pink-footed geese, and such things as great grey shrike in the neighbourhood.

It was splendid, beginning with the sight of a peregrine falcon lilting oil with prey in talons as we came over a skyline and finding a lone snow- bunting hopping about like a sparrow.

The coast had all the good things we expected to see—rafts of scoters and a few great-crested grebes, the odd red-throated diver and rock dove.

But the big thrills were on the estuary: hundreds of eider ducks, flocks of waders, curlews, redshanks, oyster-catchers, turnstones, grey plovers, dunlin; whistles of wigeon and the stumpy forms of long-tailed ducks; red-breasted mergansers flying upriver.

But we would have missed the best but for a meeting with a bearded young ornitholo¬gist called Tim, who had seen a spotted redshank and told us where to look.

We found it, because it was kind enough to call “chewit, chewii, chewit” three times, which was as good as telling us its name.

Memorable days indeed.

This piece was first published in Januray 1980. To see more of his archived My Month features for The Scots Magazine click here.

We’ll have another update next Friday!

More…

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archive of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly but surely getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here.