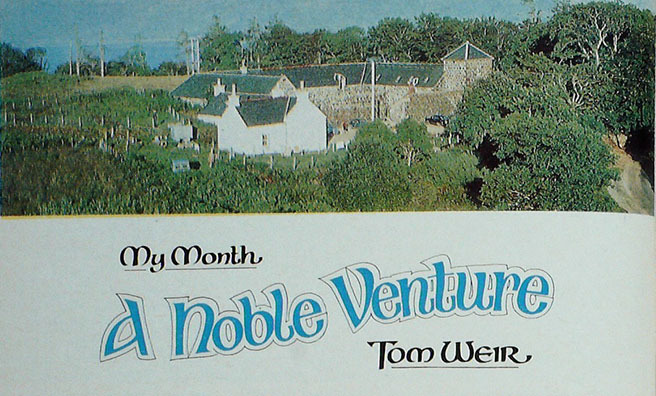

Tom Weir | A Noble Venture

Scottish Gaelic is a language in decline, but the Hebrides are still Gaelic strongholds, and in 1976, Tom Weir went to Skye to meet some of the people determined to keep this beautiful language alive

“Colaisde Gaidhlig, Sabhal Mor Ostaig?” was the query I put to a crofter coming round the gable-end of a house in Sleat. With a movement of his hand and a phrase he waved north up the road.

Had I driven off there and then he might have mistaken me for a Gaelic speaker, but in Skye it is courtesy to talk to a stranger, and as his Gaelic flowed, my face must have registered blankness, for with a friendly smile he changed to English.

“You’ll find Farquhar in the old farm steading as you turn off for Tarskavaig.”

The College of Gaelic

Sabhal Mor Ostaig is the Gaelic for “The great steading of Ostaig,” a block of grey stone beside a croft, built along three sides of a square with a walled entrance.

Inside the eastern wing I found the director of the Gaelic College, Farquhar MacLennan, in a former milking shed which now combines office, library and lecture room with no more than; a thin partition separating them.

“It’s not perfect,” he said as I sat down. “Sounds emanate. The whole building is a period piece of undoubted architectural merit, but it’s got the rundown look which people associate with Gaelic. However, the potential is here to do something positive for the language.”

The words were spoken softly, but the eyes had a steely light which belied the mild manner of his speech.

“As a head teacher in Benbecula I came up against the juggernaut every time I tried to do something for Gaelic. I was angry at the way education was structured. I wanted to promote Gaelic, so I answered an advert for this job, even although it meant having my pension frozen and abandoning a teaching career. It’s not so easy to take a leap into the dark when you have a wife and live children. But it was partly for family reasons we made the move. I was born on Raasay and went to High School in Portree.”

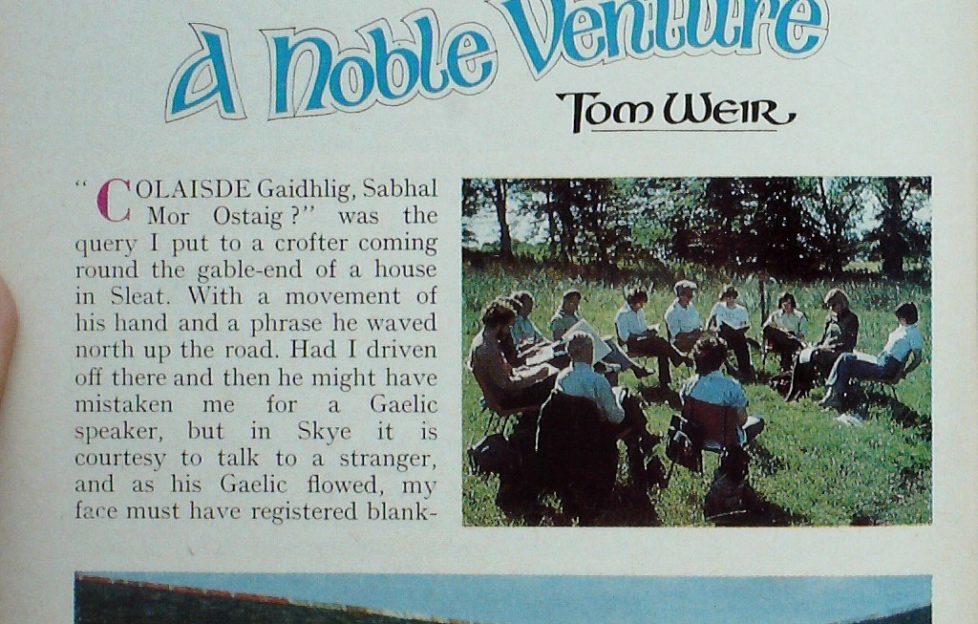

A lesson in the sunshine in the Gaelic College courtyard in its pleasant location by the Sound of Sleat.

“I would like my children to go there, too. In Benbecula and Uist there has been a decline in Gaelic which is being accelerated because of the big influx of Service personnel to the Rocket Base. I know what it was like in my own childhood on Raasay. I grew up with the feeling that to speak Gaelic was stupid. I railed at having it. It was something to be ashamed of.

“It was not until I went to Glasgow University and took Celtic Studies that I became glad to be Gaelic and proud of its literature and culture. I saw that much had been lost by neglect, but that what remained was comparable in quality to any other culture.

“In Gaelic you can express more shades of feeling and moods than in English”

” I am putting my back into this job because it would give me enormous pleasure to see Gaelic thriving again even within the Gaelic areas of the Highlands and Islands. What has happened in the last 200 years is the pushing of Gaelic into the background, yet in the richness of its adjectives and descriptive words you can express more shades of feeling and moods than in English. There is also the inheritance of the oral tradition in folk-tales and songs.”

Tact made me withdraw from the college, since Farquhar and his assistant, Miss Chirsty MacKay, of Harris, had much to do getting ready for the next group of summer school students who were due to enrol on the following day.

So I took myself off to look for lodgings, and by the luck of the draw was welcomed into a crofthouse already occupied by two young students for the course who had arrived that afternoon from Glasgow.

“We were here for a month last year and we enjoyed the college so much we’ve come back for more,” enthused Frank McArdle (21), while his brother Stephen (17) nodded assent.

“It was a lot of fun, especially the ceilidhs and the dances. There was plenty of musical talent going, too, on the fiddle and the guitar. They were a great crowd.”

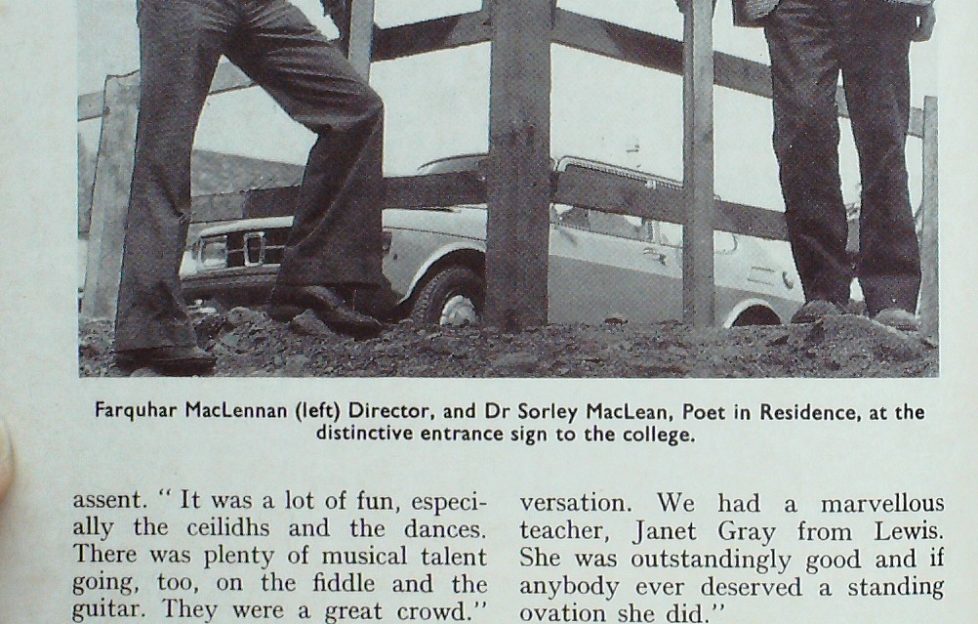

Farquhar MacLennan (left) Director, and Dr Sorley MacLean, Poet in Residence, at the distinctive entrance sign to the college.

I asked where their interest in Gaelic had come from.

“I don’t know,” said Frank. “I just got interested in it about two years before coming here. I got it from studying books and records. I’d never been to a class, and that was the reason why I came here, to find out how I was doing.

“I was quite pleased that I could understand what was being said. It was harder for Stephen, for he had started only a month before, and the whole emphasis in the college is on conversation.

“We had a marvellous teacher, Janet Gray from Lewis. She was outstandingly good and if anybody ever deserved a standing ovation she did.”

The interest isn’t limited to Scotland either

At the crofthouse we had another arrival in Dr Helen Ross, who lectures in psychology at Stirling University.

She was delighted to hear all this from the boys because this was her first visit to the college, and it was to get some practice in Gaelic conversation she had come.

A Londoner, she dates her interest in Gaelic back to the time when she was twelve and began reading books on the Gaelic language which were in the house.

Also, in the Presbyterian church she went to, there was a Lewis Gaelic speaker.

Stimulated by evening classes in Stirling last winter, her object now was to learn to speak the language for her own enjoyment.

On Monday at 10 a.m. I saw how the 25 students were divided into classes.

Farquhar explained : “You can regard everyone here as beginners at various stages of competence. My class of three are the advanced beginners, the other two classes divide fairly evenly into intermediates and absolute beginners —there might be some adjustment later when we see how they get on.”

An avid learner

While they were settling down I had a chat to a rangy Irishman who was strumming a fiddle in the manner of a guitar to produce exciting jig-type dance tunes.

“I play it that way because my instrument is the guitar and I haven’t learned how to use the bow.”

His name, he told me, was Seumas O’Bruachain.

“I was on the course for a month last year and I’ve got beyond the range of the present classes.”

It was a factual statement, not a boast.

“I’ve always been interested in Gaelic, possibly because I went to an Irish Christian Brothers School in Stoke-on-Trent. I did a correspondence course before coming to the college last year, and I’ve had live months conversation practice living here in Skye. I’m doing a study of the Social and Cultural Impact of Tourism for the Scottish Tourist Board on a grant of £880. I think anybody who tries hard could learn Gaelic in 18 months with the present teaching aids.

“Sabhal Mor Ostaig has been a great help to me. I’ve found it an ideal place to work, for its reading room and library and intellectual atmosphere. I’m sorry more use is not made of its facilities. Hardly anybody comes, yet it is available to anybody on this island. I’ve got to go to France now to do some translating work, but I’d like to find a way of living in Skye. It’s such a pleasant place to be, especially in winter when people have more time for talking.

“From my tourist survey work, which involves talking to people, I would say that most of the Skye folk are in favour of the college, yet they don’t involve themselves with it. I’d like to see them come to things that are held here, talks, debates, poetry readings, concerts, ceilidhs. It mustn’t be thought to be just for intellectuals. The college will have to publicise itself more among local people.”

“If you understand a language you understand the people”

Over soup and sandwiches at lunch time I was able to meet some of the students and hear how the classes were going.

One of the ablest was a Dutch lady, Mrs Mavis Raatgever, who told me she worked for five months in the Netherlands to pay for ten weeks in Broadford in 1971.

“I began to study Gaelic in 1968, but it was difficult with a young family, and no one to help.

“The chief pleasure of Gaelic for me is getting acquainted with people. If you understand a language you understand the people, and Gaelic was the language of my ancestors 200 years ago. I am a Fraser. I have taken “O” level Gaelic, and I would like to sit for Higher Gaelic, and perhaps do translation work. I enjoy it very much.”

Just across the table was an elderly American, George Robert MacLeod, who had come from Washington.

“My people emigrated from Loch Broom in the sailing ship Hector and landed in Pictou, Nova Scotia, in 1790. From there they branched out to Boston and California.

” I belong to the St Andrew Society in Washington, and in 1973 a few of us got together on Sunday afternoons in eacli other’s houses to study Gaelic with a Stornoway- born instructor. I’ve been to Skye once before, live years ago, at a gathering of the MacLeods. I’m living with a Gaelic family now in Tarskavaig and it’s great.”

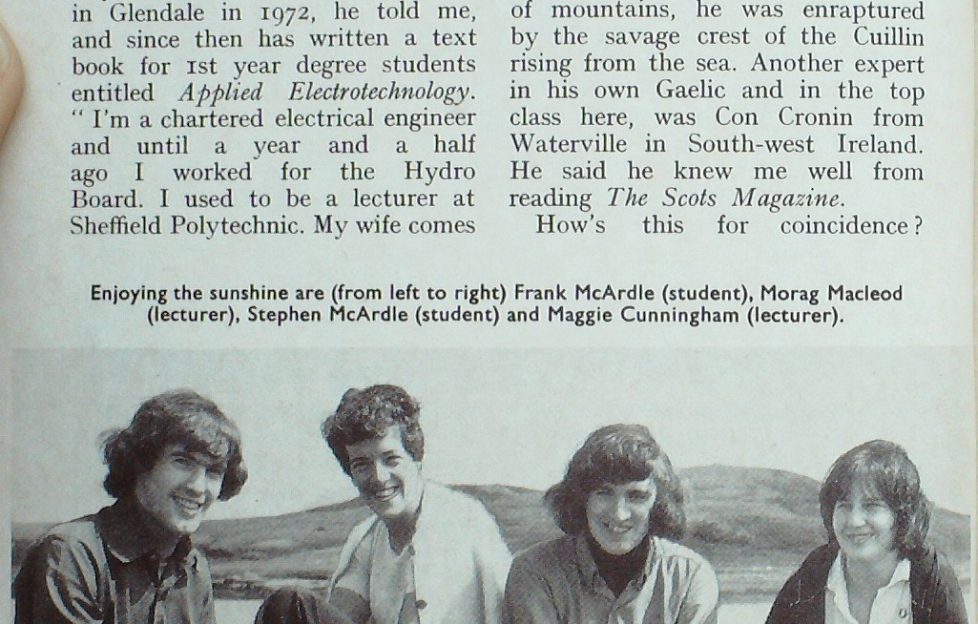

Enjoying the sunshine are (from left to right) Frank McArdle (student), Morag Macleod (lecturer), Stephen McArdle (student) and Maggie Cunningham (lecturer).

My eye was caught now by a bearded man in a kilt, with a North-English accent. To my surprise I found he was a crofter from Glendale west of Dun vegan. Cliff Laycock had taken over a croft in Glendale in 1972, he told me, and since then has written a text book for 1st year degree students entitled Applied Electro technology.

“I’m a chartered electrical engineer and until a year and a half ago I worked for the Hydro Board. I used to be a lecturer at Sheffield Polytechnic. My wife comes from Manchester. We love Skye. I am studying Gaelic because it is the language of the people around me, just as I would study Italian if I lived in Italy.”

A keen bagpiper, Cliff goes to classes in Dunvegan and hopes he might aspire to the Big Music one day.

Jim Criddle of Pontllanfraith loves the Welsh language, but chose to come north and study Scottish Gaelic because Scotland is his second favourite country.

A teacher of mathematics in Wales, and a lover of mountains, he was enraptured by the savage crest of the Cuillin rising from the sea.

Another expert in his own Gaelic and in the top class here, was Con Cronin from Waterville in South-west Ireland. He said he knew me well from reading The Scots Magazine.

How’s this for coincidence?

Chatting to one of the lecturers, Morag MacLeod, she told me she was from Scalpay, Harris. At which I said I had been there just a week or two ago, and told her how we had been able to get the self-steering gear of our boat fixed by a Kenneth MacLeod of the Red House.

“He’s my father,” she said. “Though I live in Edinburgh now and work in the School of Scottish Studies.” It’s a small Gaelic world!

Maggie Cunningham, another Scalpach, was the youngest teacher. Currently studying at Jordanhill Training College she was right to chide me for being so lazy over the years as not to try to pick up the language while travelling so much in the islands where it is most widely spoken.

The hard fact is that it never occurred to me to study Gaelic seriously, though I have always been interested in place- names.

Next day there came along a man I was especially wanting to talk with, Dr Sorley MacLean, whom I had never met outside his inspired poetry.

Retired now from the headship of Plockton High School, Sorley lives at Braes, near Portree, opposite his native Raasay.

I had not realised he has spent so much time in the Cuillin, and in no time he had carried me mentally to the tops, comparing that bit of ridge to another, and demanding to know my favourite peak. His own choice is Sgurr nan Gillean for its beauty of shape and balance of pinnacles.

Sorley was one of those who fought for Gaelic as an educational subject, and now has the satisfaction of seeing a huge increase of pupils studying it as an alternative to French at Portree High School and at the Nicolson Institute.

As Poet in Residence, with a £2500 grant for one year from the Scottish Arts Council, Sorley goes by invitation to schools where Gaelic is taught.

“Every little helps,” he said, brown eyes flashing, head cocked to the side, the very picture of a bonnie fighter.

“I talk about the broad base of Gaelic and read them poetry, a little of it my own.”

I hope they realise how privileged they are.

The founding member

Then along came Mr Iain Noble, without whom the Gaelic College would not have been set up in Sleat.

“I think Gaelic could become the first language of the islands rather than the second. It is a fact that bilingual people attain higher linguistic standards than monoglots. To learn two languages is an instinct in the young. I actually believe economic problems would soon vanish if there was a spirited revival of Gaelic.”

As he talked I found it hard to realise that this enthusiastic young man had given up a successful career as a merchant banker to buy 20,000 acres of Sleat because he loves the Highlands and Islands and believes their problems can be solved.

In four years he has impressed the Skye folk by the speed at which he learned to speak Gaelic, and by the number of jobs he has created by the opening of a “Skye Crotal” knitting mill and in getting fishing trawlers to work.

“We could do so many things here, like the repairing and building of boats. We could make equipment, nets and pumps and winches. Then there is fish processing, freezing, drying. We could market it, too, using our own ships. I want bright people to stay and work in the Hebrides, as the Faroese people do on their islands.”

Iain, like me, has been to the Faroes, and we talked of how the Faroese culture and language has blossomed so inspiringly with the assertion of national identity.

Isleornsay where lain Noble stays. The little community has revived thanks to lain Noble’s inspiration

Isleornsay where lain Noble stays. The little community has revived thanks to lain Noble’s inspiration

The land area of Skye is about the same as the Faroes, and in 1900 they carried equal populations of 15,000. Today in Faroe the population is 40,000, while Skye can muster only 7000.

“In Sleat I am trying to reverse that trend. As an incomer I am sticking my neck out — and I know it might be chopped, as was Lord Leverhulme’s in Lewis half a century ago. That’s a risk you have to take. There could be a feeling against me, that in favouring Gaelic speakers for jobs, I am having a dividing effect on the community. But I happen to believe that the Hebrides will never look back when the Gaelic language becomes a source of pride.

” As to the college, I would like to see it sponsored by the local authority and given a lump sum of cash to carry out basic repairs to the building. We need to have hostel accommodation for students and I would like to see a minimum of two or three bursaries for Teaching Fellowships. Our aim is to be a fully- fledged education centre offering two-year courses in modern Gaelic studies on practical, not esoteric lines.”

It is not such a remote dream as perhaps it once sounded, for, since the setting-up of the Western Isles Region, a drive has begun, not only to maintain the language spoken by over 80 per cent, of the population, but increase its use, beginning in the primary schools.

This bilingual education project costing £70,000 over three years is being directed by Lewisman John Murray.

Murray has said: “I knew children who were despised by their classmates for speaking Gaelic, and mothers who would beat the language out of their children. But now we have a situation where the middle classes are ‘rediscovering’ the language.

It is not such a remote dream as perhaps it once sounded

“It is becoming not only respectable but inspirational. It may be a sad irony, but as Gaelic becomes the language of the privileged, so its chances of survival are improved.”

Murray’s aim is to increase the use of Gaelic as a working language in primary teaching, the language in which subjects are taught, as distinct from Gaelic as a formal study.

By this means pressure might be brought on secondary schools to adapt their curricula. Given that the bilingual experiment is a success for Gaelic, then it could be that the success of the Gaelic College in Sleat is assured.

Meantime, the problem for the college is one of simply staying alive. Farquhar outlined it as we had our concluding talk in the Common Room.

“Cash is the problem. Even my own salary is on a declining scale over three years, because the £9000 grant of the Gulbenkian Foundation was given on the understanding that the college would be self-supporting within that time.

Dr Gordon Barr, the first director of the college, worked for nothing for a whole year.

“We depend largely upon charity although, as yet, the college has not achieved official charitable status. While the constitution for the college has now been legally formulated, the final decision as to the granting of charitable status rests with Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Taxes. Needless to say, his decision is anxiously awaited, since a favourable outcome would mean that the college had access to probable support from other British grant-making trusts.

“However, I have managed to reduce the overdraft, while cutting costs to the bone for students, with fees at £28 for a fortnight, and lunch and dinner meals at cost price. In addition to that it costs about £2.50 for bed and breakfast accommodation in Gaelic-speaking homes. There is a chance that we might manage to utilise a residential block nearby in one of the Armadale Castle out-buildings belonging to the Clan Donald Lands Trust. This could reduce the accommodation costs for the not-so-well-off students.

“We need university status. That would be the ideal. Meantime, we manage to pay staff costs from the £4000 given by the Scottish Education Department. We have applied for £20,000 from the HIDB having already received £5000 as a non-economic grant. We have to be grateful to our ‘Friends of the Gaelic College’ who take out membership and pay £2 a year, and this brings in about £600. We also make a little money from the sale of books and teaching aids.”

I asked him what he had discovered that would enable him to improve the summer courses.

“I think the first one this year, lasting a full month, was a bit of a deluge. Teachers and students were beginning to wilt in the last week. I’ll possibly experiment with a three-week course next year.”

Rekindling the interest in Gaelic

“We could certainly do with some more students, especially in the younger and more vital age groups. I’d like to get the Highland Region to send teachers here to learn Gaelic. The world-wide interest in Gaelic is not reflected in the very region in whose educational sector one would expect to find a dynamic, purposeful approach to the language.”

It is nice to hear a bit of plain speaking of that kind, but then fighters for the Gaelic tongue have never been mealy-mouthed.

Considering the history of deliberate suppression of Gaelic by official educational institutions, it is astonishing that something like 80,000 still speak it.

And enthusiasts believe that the despised tongue that was systematically destroyed can be systematically recreated. That is what the Gaelic College is about, and it is also the reasoning behind the Western Isles Region bi-lingual experiment.

Here is a fragment taken from an address, from a lecture by the late Professor W. J. Watson on “The Position of Gaelic in Scotland,” delivered in 1914 at Edinburgh University :

Gaelic attained its greatest extent in the eleventh century, when at the time of Carham in 1018 it ran from Tweed and Solway to the Pentland Firth . . . probably Caithness and Lewis spoke Norse only, while the Isles, the West Coast, and much of the North-East as far as the Beauly valley would be to some extent bilingual.

Gaelic was the first language of Scotland as a united nation, and as a Skyeman said to me it is no burden to carry it along with English.

The Gaelic College is still going strong, and you can find more about it on their website, here.

More From Tom

More from Tom

- More instalments every Friday