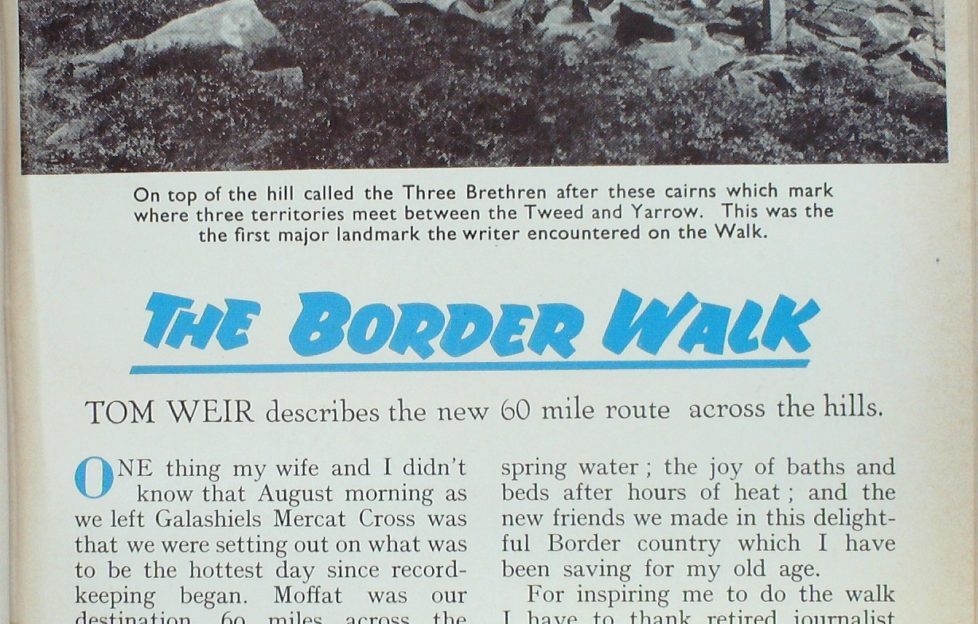

Tom Weir | The Border Walk

In November, 1975,Tom Weir walked the brand-new 60-mile route across the Kills, roughly along the track of the current Sir Walter Scott Way…

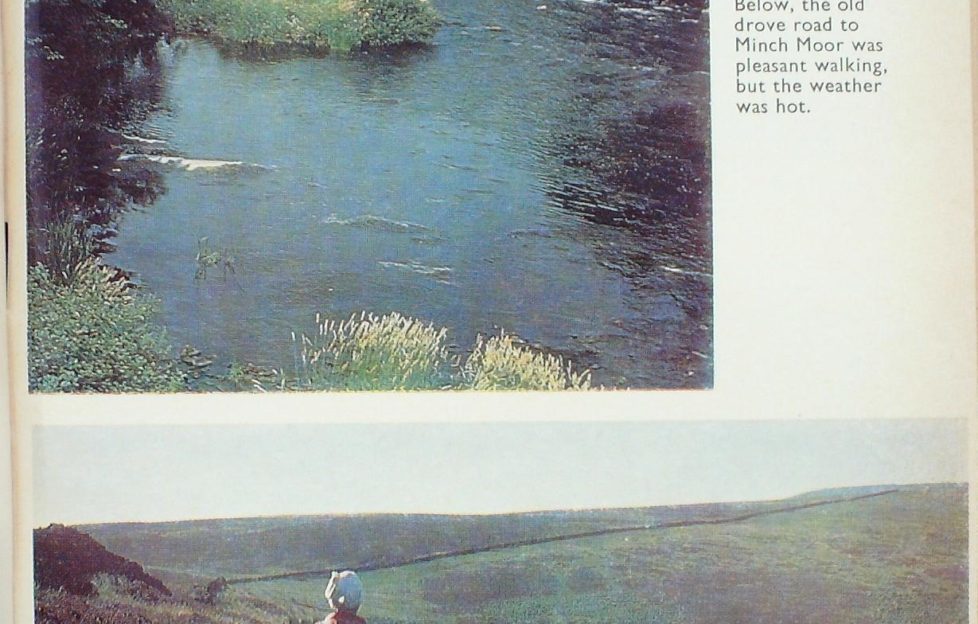

ONE thing my wife and I didn’t know that August morning as we left Galashiels Mercat Cross was that we were setting out on what was to be the hottest day since record-keeping began. Moffat was our destination, 60 miles across the hills, and the soles of our feet were to know all about it by the time we got there. Still, there was no day as uncomfortably roasting as the first one, nor any 19 miles on which we were to be so thirsty or so plagued by flies.

Not quite the recipe for enjoyment ? In fact, we look back upon the three and a half days of the walk with great pleasure, remembering its contrasts: torturing thirst quenched by long awaited ice-cold spring water ; the joy of baths and beds after hours of heat ; and the new friends we made in this delightful Border country which I have been saving for my old age.

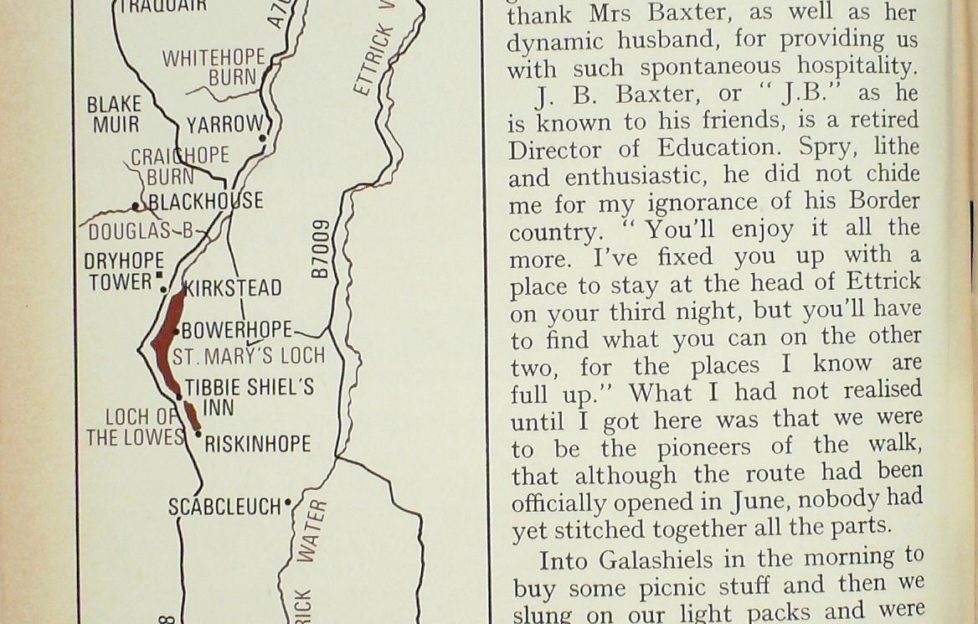

For inspiring me to do the walk I have to thank retired journalist John M’Murtrie of Galashiels. He it was who told me of a long-distance route, entirely on rights-of-way, which had been worked out across the hills taking in bits of Selkirkshire, Peeblesshire, and Dumfriesshire, beginning at the Gala Water and Tweed, then by the Quair and Yarrow into Ettrick and over the hills to Moffatdale. Better still he put me in touch with an architect of the route, Mr J. B. Baxter of Lindean, one of the moving spirits in the formation of the Scottish Borders HillwalkW Club in 1974.

” Phone Mr Baxter for details of the route,” John had advised. And the crisp voice that answered my call didn’t waste any words.

” Good, you want to do the Walk. You’re leaving tomorrow? Come here and look at the maps. Bring your wife and stay the night. You can leave your car here and I’ll pick you up when you finish at the other end.”

It was a most generous offer, and we have to thank Mrs Baxter, as well as her dynamic husband, for providing us with such spontaneous hospitality.

J. B. Baxter, or ” J.B.” as he is known to his friends, is a retired Director of Education. Spry, lithe and enthusiastic, he did not chide me for my ignorance of his Border country.

” You’ll enjoy it all the more. I’ve fixed you up with a place to stay at the head of Ettrick on your third night, but you’ll have to find what you can on the other two, for the places I know are full up.”

What I had not realised until I got here was that we were to be the pioneers of the walk, that although the route had been officially opened in June, nobody had yet stitched together all the parts.

Into Galashiels in the morning to buy some picnic stuff and then we slung on our light packs and were off.

” See you on Thursday afternoon !” grinned J.B. as we took a track marked : ” Public Path to Yair Bridge.” Striking off from the minor road which contours the wooded west flank of Gala Hill, our path went into the open almost at once to begin climbing a grassy shoulder.

The way ahead looked exciting…

The path was no more than a sheep track leading us up and through a little copse into what could almost be called downland, rolling bumps intersected by dry- stane dykes and dotted with sheep and cattle. Then the ground fell away and we began dropping from 900 feet on a broadening track into sloping fields of barley. The way ahead looked exciting, for below us was the Tweed, and rising over it a thousand feet of hanging conifers whose culminating point was the Three Brethren, our first peak.

It was getting on for midday now as we crossed Yair Bridge and took the private road leading to “The Yair.” The right-of-way path to Yarrow strikes off just past the lodge gate, and we were glad to accept a glass of water from the lad)’ of the house, who also gave us a warning…

“You’ll find the path difficult—it’s overgrown and the trees are very close.”

She did not overstate the case : we tried various lines before we found any kind of path. The best way is to keep as close to the edge of the ravine 011 the left as is reasonable. Fearfully hot as it was in the ravine, we forgot about the flies for a time so colourful were the butterflies and moths.

We were truly in the Sir Walter Scott country of romance now…

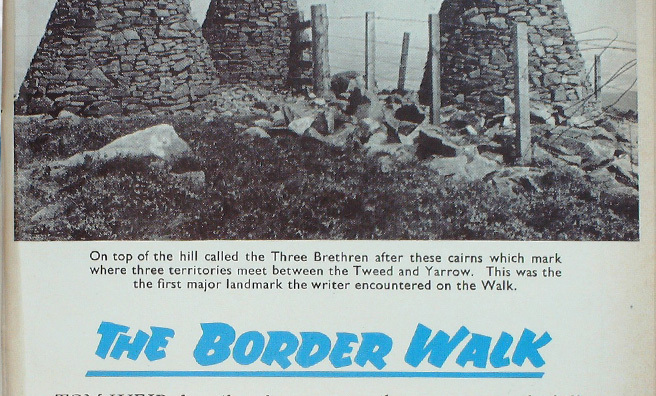

We struck sharply upwards when we came to a heathery forest ride between the well-grown trees. It was steep ; the sweat dripped from us and the flies were in clouds around our heads. Marvellous at last to win clear of these enclosing trees, feel a mild breeze, and see a ridge ahead leading all the way to the pointed top of the Three Brethren (or Brothers).

I had not realised that the Three Brethren are boundary cairns, each marking the limit of its owner’s property. They divide the lands of Selkirk Burgh from those of Yair and the lands of Philipshaugh. Medieval documents refer to them as the “Thre Bridder,” and every year the Selkirk Souters come to inspect the south cairn to preserve their march. This is the farthest point in their 12-mile Common Riding, and this year 385 riders clattered round the cairns.

We were truly in the Sir Walter Scott country of romance now, for jutting eastward above dim Tweeddale the volcanic knobbles of the Eildons rose commandingly above everything else. The breeze had dispersed some of the flies and it was good to lie back, boots off, and eat an overdue piece.

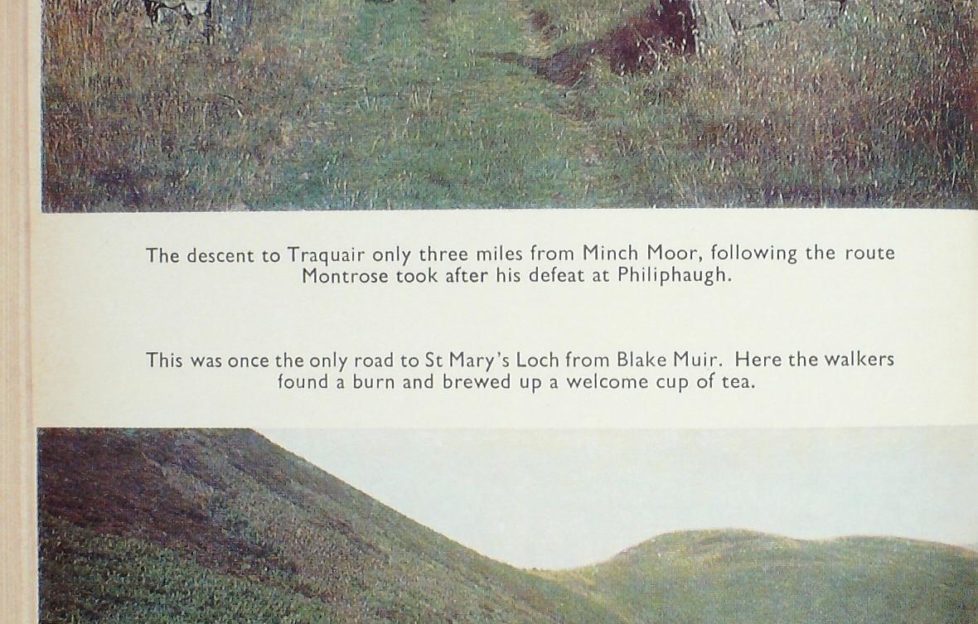

Packs on the backs again, we now strode out along the crest of a ridge, on the worn line of a drove road from Scotland to England. From Falkirk the cattle climbed from Traquair by the Minch Moor and Broomy Law on their way to Ettrick. And as we walked along its crest we thought of Montrose who used the road in the reverse direction after the shambles of Philiphaugh when the remnants of his beaten army straggled northwards. But down in Yarrow the Covenanters were not content with victory ; still thirsty for blood they disgraced themselves by killing prisoners and women and children camp-followers.

The drovers and the escaping troopers chose the hill tops for a good reason. The flat going along the grass and heather tops is a lot easier at 1600 feet than down in the twisting valleys if your direction is north or south.

Thirst was the only tiling that was spoiling our enjoyment, nor were we perspiring less for the sun blazed as fiercely as ever. Both of us felt slightly squeamish with dehydration, but our thoughts were fastened on a dot on the map marked ” Cheese Well.” Our friend J.B. had told us smilingly to be sure to make the well an offering of cheese when we stopped to take a drink.

” We couldn’t be past that well,” Rhona said despairingly as we rose over the flank of Minch Moor. We looked at each other, then sat down in the middle of the track to check the map. As we sat I voiced something that had been at the back of my mind.

” If we can’t get digs in Traquair tonight, I have a contact at Walkerburn. He owns the Tweed Valley Hotel. I don’t know him— we’ve only spoken on the phone. But I think he would collect us from Traquair if we gave him a ring.”

Within minutes of voicing that remark, Rhona tapped me on the shoulder.

“We’re about to be run down by a car!”

The two occupants of the yellow Volvo were grinning as they jolted down the grassy track towards us.

” Well,” I said, ” I wouldn’t have been surprised to meet a camel in this waterless desert, but I hardly expected to have to get out of the way of a car !”

The driver laughed and assured me that normally he would be walking, but because of the long dry summer he was risking the car. They had come up to have a look at the grouse situation.

” I run the Tweed Valley Hotel,” he said, ” and our guests come shooting up here. That’s the helicopter pad over there.”

But before he could go any further I was telling him who I was and we were shaking hands. I told him what I had been saying to my wife about phoning him if we were stuck.

” Of course ! Jump in,” he said. ” We’re going there now.”

Thirsty as we were I had to refuse.

” No, we must finish this stage of the walk on foot, but if you could collect us at Traquair and return us there in the morning –”

He didn’t let me finish.

” Right. I’ll fix you up with a room and dinner and drive you back in the morning.”

They drove off, and fifteen minutes later we were at the Cheese Well, parting the thick green scum covering the surface and finding underneath the cold clear liquid we craved. We shall not forget that drink in a long time.

Spruce forest stretched ahead of us as we dropped from 1500 feet to opening views of parkland and yellow grain fields, the white cottages of Traquair nestling beneath hilltops soft in the haze. The last stretch of the drove road through the houses took us to the war memorial. We were on time and the yellow Volvo was advancing to meet us as we got there. The iced lager, baths and welcome meal which followed seemed almost too good to be true. After it Rhona felt so fresh she went out for an hour to look at Walkerburn and see the sunset.

Walkerburn is about five miles from Traquair, and Charles Miller had us away by 9.15 a.m. to set us down at the war memorial to continue our route. He would like to have been coming along, especially since the air was cooler and the hills ahead looked inviting. The un-signposted right-of-way goes uphill as a farm track just past Kirk- house, a mile and a half south of Traquair.

Our target was Blake Muir (1512 ft.), but we hardly noticed the climb so gradually did our pleasant hill shoulder rise through fields and pastures. The path was overgrown with whins, but it became broader higher up. At one time this was the only road to St Mary’s Loch, our destination. After Blake Muir it was joyful to find a burn in the col between us and the next hill at 1524 feet, and we wasted no time in getting out some bars of solid fuel and getting a brew going in our wee teacan.

With no real path before us from here, we simply struck over the steep heathery hilltop and steered south-west into a dip and up over the next bump at 1561 feet. Now we looked into the hollow of the Craighope Burn and saw a broad path taking a line across our hill above it. Down there out of sight lay Blockhouse, where James Hogg the Ettrick Shepherd worked for ten years, so we were on historic ground and it was nice to think how often the feet of that remarkable man must have walked our path. Then as we turned the corner to the house, three work horses came out of the stable, and I had the feeling that little had changed since Hogg’s time.

There are two cottages at Black- house, but nobody lives permanently in them now. Between the cottages is the ancient ruin of Blackhouse Tower, with a warning notice saying it is dangerous. It was dangerous even when it was built, since it was from here the powerful house of Douglas sprang, and here the Black Douglas recruited troops for Robert the Bruce. And up on the hills we had walked over, the ” Douglas Tragedy ” was enacted, when Lady Margaret Douglas and her lover, eloping from Blackhouse over the hills to Tweeddale, were overtaken by her seven avenging brothers. Her brothers were slain, but Lady Margaret and her lover died that night of their wounds. A famous ballad tells the fierce story.

Shakespeare acknowledges the power of the Douglases when he wrote in Henry IV, part I:

The Douglas and the Hotspur both together

Are confident against the world in arms.

But it is to Sir Walter Scott and his collected Border Minstrelsy of 1802 that this land and its people come alive and history speaks. Scott was to meet destiny at Blackhouse, too, for it was there he met Willie Laidlaw, the son of the Blackhouse farmer, who became his closest friend and helper to the end of his life.

I felt there was a kind of haunted atmosphere about Blackhouse, where Hogg worked through the greatest snowstorm that ever struck the Border Hills. He describes it in his Collected Tales. The year was 1794 and the snowstorm killed seventeen shepherds as they tried to rescue their buried sheep. Hogg remains one of the greatest lads o’ pairts that Scotland has produced. He claimed only six months’ schooling in his life, yet he could read the Bible before he could write, and by 26 years of age was polishing off songs and ballads, pastorals and poems published in 1800. As a sheep farmer he was dogged by failure, while his writing grew in variety and power.

No landscape can remain just a landscape when men like Hogg have trodden it. Our route ahead lay across the Douglas Burn, south-west round the flanks of the Hawkshaw Rigs, beyond which a neat little pass lay ahead of us, with a silver slit of St Mary’s Loch just showing through. A sharp little climb and we were over, looking down to where the Yarrow emerged from the three- mile-long loch. It would have been fine to desccnd to Tibbie Shiel’s Inn and savour the place where Scott, Hogg and their cronies spent so many con¬vivial nights. But the inn was booked out, so we headed for Kirkstead on a path which kept round the hill to Cappercleuch, where we had the good luck to find supper, bed and breakfast with Jack and Angela Bell, who went out of their way for us since they do not normally take in visitors.

“I couldn’t begin to tell you all the kindnesses we’ve had”

No explanations were necessary with this pair. There was a shout of “Come in,” when we knocked at the door, and within moments we were accepted, tea was handed to us, baths were run, and in no time a fine supper was on the table. Their easy hospitality made us feel as if we had known them all our lives as we sat yarning and hearing how they had come to stay here beside the Megget Water.

” I worked for 28 years for the Port of Bristol Authority,” said Jack, ” and after I retired we decided to buy a motor-caravan, come up to Scotland and spend a while exploring it. Whenever we came to St Mary’s Loch we knew this was where we wanted to stay. This cottage was empty. I found out it was owned by the Earl of Wemyss and March and I had the cheek to write and ask for it. That’s how we got it to rent. We moved in three years ago, and I’ve been busy ever since, plastering, painting, making a garden, turning myself into a handyman.

“It’s been wonderful. You have to live among the people here to appreciate how good they are. I couldn’t begin to tell you all the kindnesses we’ve had ; offers to do things for me when Angela was seriously ill, cards and phone calls. We never want to leave here, there’s so much to see and do. We get red squirrels here, and we saw a roe deer swimming the river the other day.”

Some of that kindness was passed on to us, for not only did we have the best of everything, but Angela had baked Cornish pasties and raspberry tarts to see us over the hill when we left the following morning in a thundery overcast. First we had three miles of road to the Hogg monument overlooking Tibbie Shiel’s Inn. Here Hogg sits with his dog at his feet, with the words under them :

At evenfall, in lonesome dale

He kept strange converse with the gale,

Held worldly pomp in high derision

And wandered in a world of vision

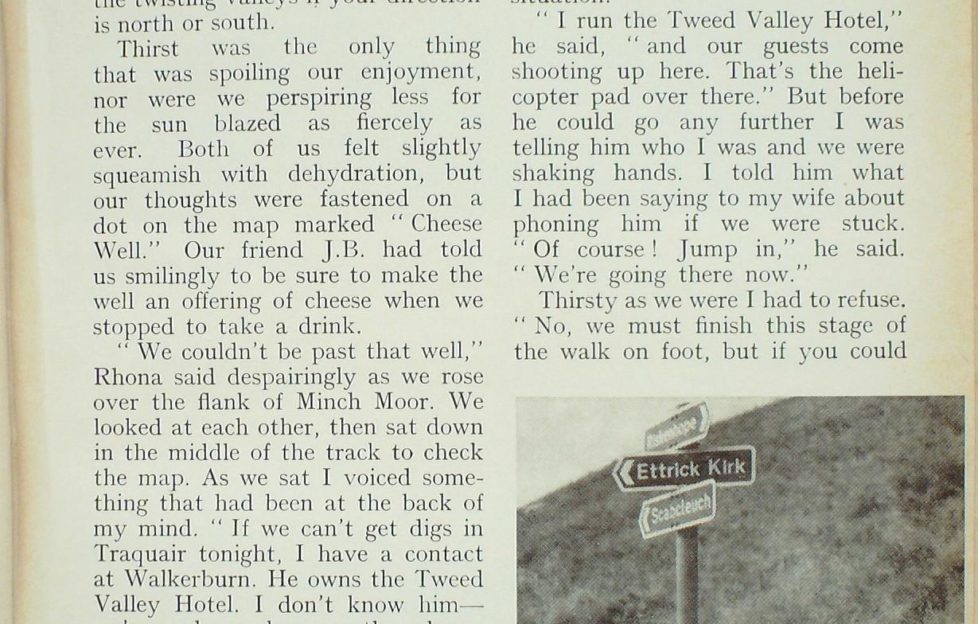

The way ahead slanted uphill above the Loch of the Lowes to Riskinhope to hit a grass coffin-road climbing Pikestone Rig and crossing the ridge at 1500 feet to slope above the Whitehope Burn. My intention had been to abandon the path and strike south-west across the tops to the head of Ettrick, but black clouds boiling over the peaks had the threat of thunderstorm in them, so we kept to the pleasant path. At this height it was not the kind of place to expect a signpost, but there it stood, pointing left for Ettrick Kirk and straight on for Scabcleuch over a wee pass.

In Border terminology a ” cleuch ” is a narrow and steep-sided burn, while a ” hope “is more of an easy grassy bowl with the stream meandering in its centre. Scabcleuch was the perfect kind of cleuch, its banks forming little ravines with waterfalls and trees, and little alps inviting picnics. We chose awaterfall with a fine pool below it for bathing our feet while the tea boiled up. It was an hour made really pleasant by the sun coming out to temper the breeze. And it was here we met the only two walkers on our entire Border traverse, a mature couple going up by the way we had come down.

Ettrick came into view as we rounded the cleuch, an almost Highland strath margined with little clusters of trees walled by steepish green hills. It was just a mile from where we stood that Hogg was born, and there he lies buried. There is 110 doubt that it was at the home fireside that he got his education— from his remarkable mother who fed his imagination on ballads and tales of kelpies, brownies, giants and kings. And it was in his mother’s house he first met Scott, plain Mr Walter, in 1802.

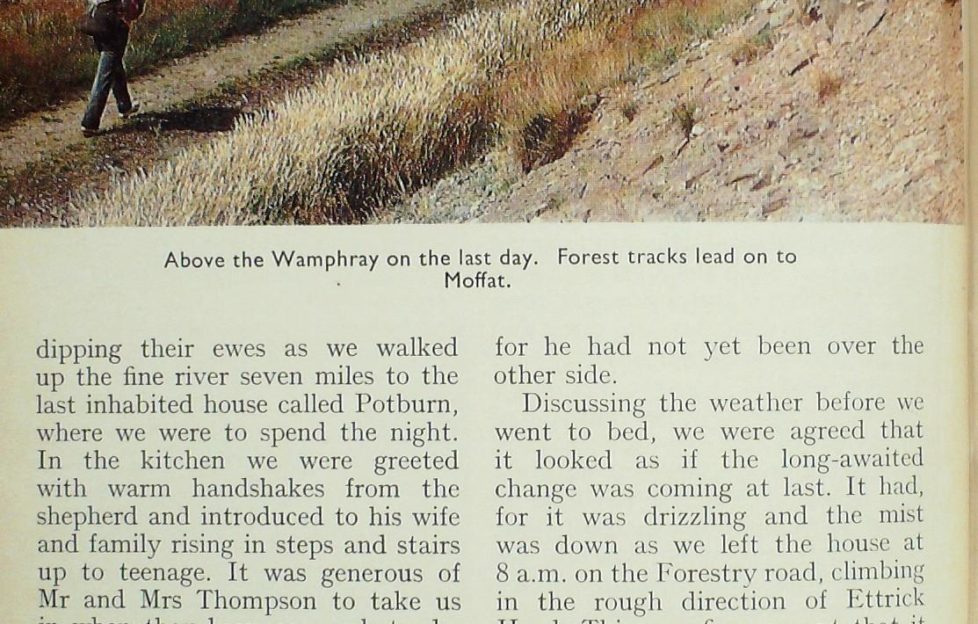

The old way of life still goes on in Ettrick, and shepherds were busy dipping their ewes as we walked up the fine river seven miles to the last inhabited house called Potburn, where we were to spend the night. In the kitchen we were greeted with warm handshakes from the shepherd and introduced to his wife and family rising in steps and stairs up to teenage. It was generous of Mr and Mrs Thompson to take us in when they have so much to do.

” You’ve just to accept becoming members of the family,” said our host as Mrs Thompson sat us down at the kitchen table and put a fine dish of mince and potatoes in front of us. It was the way we like it— no ceremony, but plenty of hospitality.

The family are from Northumberland and were not long there. They told us they had fallen in love with Ettrick. Unfortunately, Mr Thompson could tell us nothing about our route for the morning for he had not yet been over the other side.

Discussing the weather before we went to bed, we were agreed that it looked as if the long-awaited change was coming at last. It had, for it was drizzling and the mist was down as we left the house at 8 a.m. on the Forestry road, climbing in the rough direction of Ettrick Head. This was fine, except that it led us into a dim world and petered out, leaving us to guess whereabouts we might be for tackling the 1400- foot col ahead.

All I could do was maintain a compass bearing in a tussocky world without landmarks. But I knew the ground must fall away into a ravine, and we should maintain a traversing line however steeply the hill be anything else but right,” I said in a firm voice to reassure myself as much as my doubting wife. Hut it was a relief all the same when a brightness gradually began to grow around us, and suddenly we were looking into a canyon of impressive depth where the mist swirled and gully water glistened.

This was stimulating, the most exciting place we had seen in the Borders, and becoming more rugged- looking every moment as the mist steamed off a big broken face of scree and rock on the north side. And at the same moment, in front of us we saw a narrow path threading the crumbling wall of our side of the canyon. The compass course had been pretty good, but the proof of it gave us a fine feeling of elation. Oh, to have had a bit of light for a photograph, but the gloom was unrelieved as we threaded the landslips to a point where the ravine angled sharply north-west to empty its water by the Selcoth Burn into the Moffat Water.

Our direction lay the other way, southward into a narrow pass cleaving between Coomb Cairn and Cowan Fell, where the River Wamphray rises in a narrow Lairig Ghru. I was looking forward to this place, but it had been despoiled by ploughing and tree-planting when its wild character should have been preserved.

The feeling of anti-climax was intensified when we emerged from the pass into a vast geometrical pattern of forestry reaching almost to the tops of all “the hills. We also stepped on to a network of tracks climbing and dipping around T200 feet. No problems of route-finding for we simply kept to the main track which gradually dipped to the Cornal Burn in good time for tea.

Descent from here was sheer pleasure as the valley opened out and ahead of us in hazy sunshine stood the red church tower of Moffat and its white houses in a shimmer of fields, green ridges and blue hills. All too soon we were crossing the Moffat Water and a two-mile tramp took us into the town at 1.30 p.m. As if to welcome us, the sun came out full strength to brighten the busy streets.

With plenty of time on our hands, since we did not expect J.B. until 5.30, we betook ourselves to the boating pond and sought a shady spot under a tree to put our feet up and enjoy the sight of other folk enjoying themselves in the wee boats and on the bowling green.

At 4 p.m. we decided it was tea- time, which would be a pleasant interval until J.B. arrived at 5.30. Our timing could hardly have been more perfect, for as we crossed the road we were hailed with a shout. It was our friend.

” I’ve just arrived,” he said, but he had no time to say more for at that moment he was greeted by a couple. He shook his head in disbelief.

” Mr and Mrs John M’Murtrie—meet Mr and Mrs Tom Weir!” Another coindidence, for it was the same Mr M’Murtrie who had first suggested that I do the Border Walk. He had no idea I had done it, but happened to be paying his annual visit to Moffat that afternoon.

We had a grand tea party together, then into the car for the fine drive back to Selkirk, by way of the Moffat Water to Yarrow. Yet I felt as I always do in a motor car, that the countryside had retreated from us, and that to find it again we would have to leave the tourists and the busy roads behind us. Only then, through the feet, would the imagination work.

In the past I had dismissed the Border scenery as being ” nice ” but not exciting enough for me. Now that I had walked over its uplands and absorbed some of its history, the landscape has come alive. Most of all I enjoyed the loneliness of it, a friendly loneliness because, empty as it is, the hand of man is everywhere on the hills, in dykes, in paths, in ruins, sheep and woods. You are walking over a land full of stories, a land which was the extremity of Scotland until the Union of the Crowns, when it became the middle of Britain.

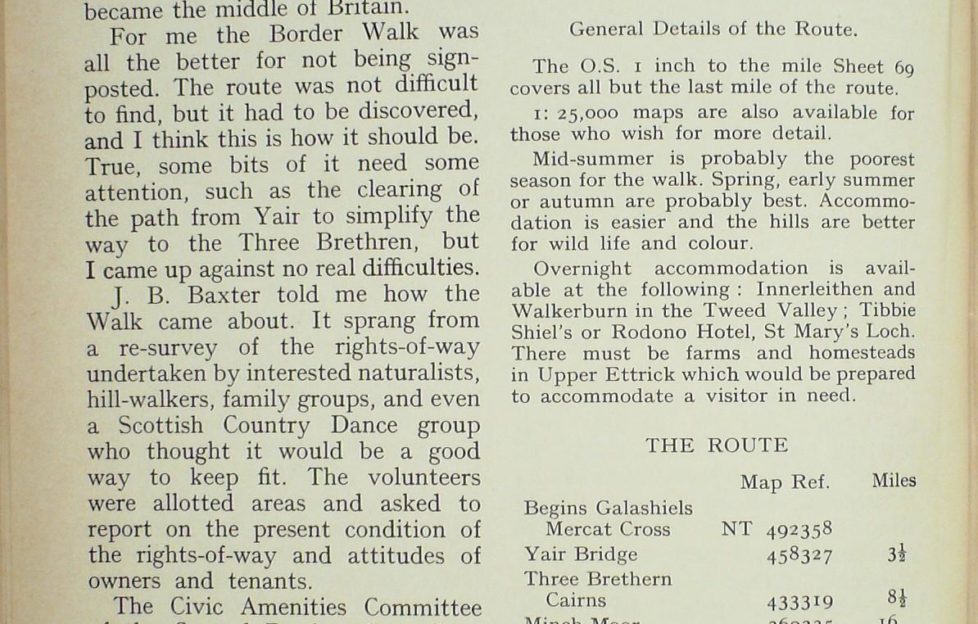

For me the Border Walk was all the better for not being signposted. The route was not difficult to find, but it had to be discovered, and I think this is how it should be. True, some bits of it need some attention, such as the clearing of the path from Yair to simplify the way to the Three Brethren, but I came up against no real difficulties.

J. B. Baxter told me how the Walk came about. It sprang from a re-survey of the rights-of-way undertaken by interested naturalists, hill-walkers, family groups, and even a Scottish Country Dance group who thought it would be a good way to keep fit. The volunteers were allotted areas and asked to report on the present condition of the rights-of-way and attitudes of owners and tenants.

The Civic Amenities Committee of the Central Borders Council of Social Services had approval from Selkirk County Council for the whole idea. Ideally the Walk should have finished at Langholm, but this proved to be out of the question because of landownership problems. But it was demonstrable on the map that a walk from Galashiels to Moffat could be done on rights-of- way, apart from short connecting links of public roads. The Forestry Commission had no objection to the use of their roads, so the way was clear.

Appropriately, Mr John Harrison, a former Convener of Selkirk County Council, a lifelong hill-walker and a fighter for rights-of-way, presided at the official opening last June. In the Borders it is becoming increasingly important to preserve every right-of-way because of the large-scale nature of private and State forestry. An active body of public opinion is the best safeguard.

For more of Tom’s columns check back here every Friday.