Tom Weir | Off The Beaten Track

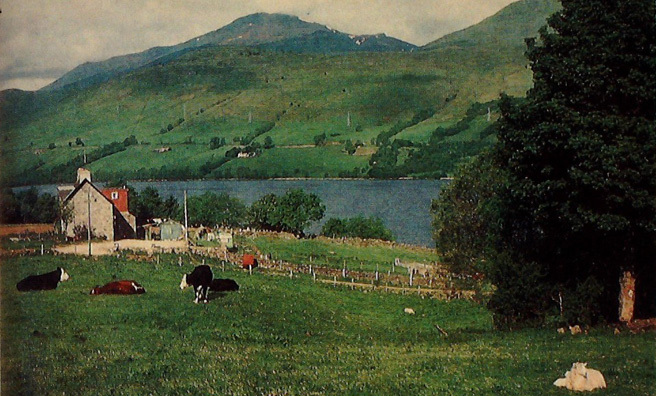

Waking up on Loch Tayside and looking on Ben Lawers pin-sharp under crisp billows of white clouds moving over its grey top was to have an immediate feeling of wellbeing, especially when I couId smell the coffee and toast, and hear the rattle of cups as my friend Pat Sandeman prepared breakfast for the pair of us.

We had arrived at his weekend cottage north of Ardeonaig at dusk on a grey, drizzly night, so the pleasure was all the greater to find that the wind had gone round to the north and the sun was playing hide and seek amongst the scudding cumulus in the blue.

We had foregathered for a day on the hill, but before we drove away from the house Pat had things to show me: a spotted flycatcher brooding its eggs in the clay shell of a swallow’s nest under a gable-end ; his rock garden blooming with plants he had gathered in the high corries of many a Perthshire ben; the Caledonian pines from the Black Wood of Rannoch he planted as tiny seedlings over twenty years ago and which now stand high and shelter his house and garden.

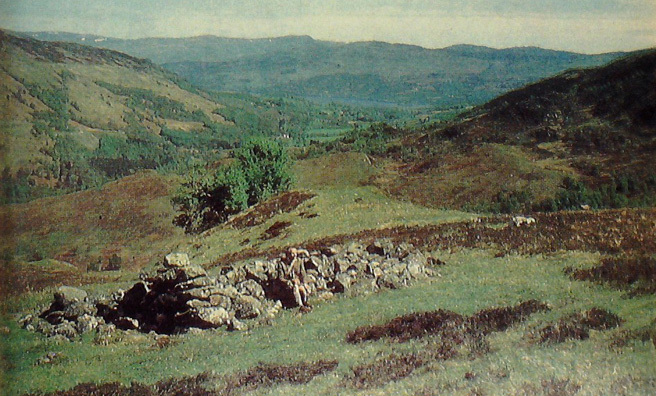

And below the house and above the shore lie pointed out the ruins of a sizeable crofting township.

“The old things interest me”

“That’s where I got this,” he said, taking me inside to show me a tiny piece of the blacksmiths’ art, a hinged swey, beautifully ornamented. “Yes, the old things interest me — works of craftsmanship like this old spinning-wheel made from driftwood. I rescued it from an abandoned black house on Eriskay. Nobody wanted it. All it needed was a wee part. Look how neat everything is. It still works.”

Pat had forged a close attachment to Perthshire long before he had a cottage on the south shore of Loch Tay. In the 50s I knew him as the great authority on the golden eagles of central Scotland, using up incredible amounts of energy to establish how the birds were doing in terms of breeding success, and proving in subsequent years that much had to be done in the way of protection if the birds were to hold their own against persecutors and pesticides.

I had the company of an exceptional character

Beyond that I didn’t know a great deal about him, except that he was a player of the big music on the bagpipes and had a great fondness for the Gaelic. Then about eighteen months ago we made the first of several expeditions together, and I knew I had the company of an exceptional character, a grandfather with the enthusiasm of a teenager for the bens and glens.

Right now his proposal was that we should head round the east end of Loch Tay and go by Keltneyburn and the Braes of Foss to Loch Rannochside. Until now I had not appreciated what a density of crofting population this shore must have carried in the past, for there are ruins everywhere, and fine stands of natural oak and birch all the way to Kenmore. Old hill paths lead south-west to Comrie and Crieff.

Pat had imported white-tailed eagles from Norway

Swinging over the shoulder of Schiehallion, then down from the bare heights to the oaks of Dunalastair Reservoir, Pat told me of how, years ago, before the osprey re-established itself on Speyside, he had tried the American expedient of setting up cart wheels on high trestles in the hope that prospecting birds would use them as platforms for their big nests. And also, at his own expense, he had imported white-tailed eagles from Norway and set them loose in Glen Etive in the hope that they would settle and breed.

His experiment failed, but it is still being pursued by the Nature Conservancy Council, who this summer imported another eight young white-tailed eagles from Norway to be released in the Hebrides to add to other importations in the past two years. The Isle of Rum is the centre of the experiment, and last year, far to the west of that island, on Mingulay, I had the thrill of seeing my first white-tailed eagle in Scotland beating over the cliffs, showing me its wedge-tail, dark plumage and broad wings as it passed below me.

A new talking point arose as we motored along the south side of Loch Rannoch — the good work of the Forestry Commission in laying out picnic sites in attractive birch glades, with stout tables and benches facing towards fine views, while at the Carie Burn campers can enjoy a secluded camp site on a grassy flat ringed by trees, from which point a fine range of forest walks are signposted, all of them within the area of Caledonian pine forest.

Pat and I are not fond of tourist tracks

However, Pat and I are not fond of tourist tracks and don’t mind getting our feet wet, so we chose to begin our stravaig at Lochs Finnart and Monaghan above the Camghouran Burn. The mossy ground quakes as you walk through the bog cotton and cross-leaved heath, but this is red-throated diver country, and there they were, low in the water, spear bills uptilted, grey birds whose eerie calls are the true cries of the wilderness.

Now we climbed to firmer ground for a heathery traverse of moraines crowned with Caledonian pines and cut up by birch-clad gullies where blaeberry made a carpet for white stars of chickweed-wintergreen, bearberry and cloudberry.

Wagtails, yellow as canaries, danced in the air for flies above the burn, and as we examined an anthill creeping with activity, the voice of a worried redstart began scolding, sending our eyes up to the cause, the blackcurrant eyes of a red squirrel, its yellow tail jerking above feathery ears. With one leap it was up on to a higher branch, peering down at us from the pink bow of bottle green needles, a delicate sprite of impudence.

This open wood is never dull, but I feared for it a few years ago when this bit was fenced and ploughed. Happily the natural cover has now taken over and you can see the regenerating pines though the Forestry Commission may not like the red deer and the mountain hares living inside their expensive fence. After years of neglect and exploitation by man without thought of the future of the wood, it is good to see it being managed and cared for now, and from our high vantage point we could look over its undulations and across to the grey hulk of Ben Alder, still flecked with snow above some of Scotland’s remotest country.

“That alone was worth coming to see”

Amongst the birches of the highest rocks, Pat let out a glad shout and pointed. No mistaking his favourite bird, the golden eagle, as it turned like a black aeroplane, drew in its wings, let itself fall for a few hundred feet, then caught by the wind, soared up again and this time went into a steep dive to zoom up again. Now we could see that it had a sprig of heather crosswise in its huge beak. “Well, that alone was worth coming to see,” smiled Pat.

We talked for a bit about his quarter of a century of intensive work on the golden eagles of Central Scotland when he had made it his business to know where every eyrie was situated, which pairs were having success, and why others failed every year. Evidence showed there was a lot of persecution of birds, which is why the R.S.P.B. brought in a “bounty system”, whereby keepers were rewarded if chicks were successfully raised on their ground. Pat was the arbiter. Harmful pesticides causing sterility in the birds were banished, but some persecution still goes on, and the situation is not good for eagles in certain grouse moor areas where there is prejudice against the birds.

We looked towards the end of the Camghouran track which climbs to 1600ft, and I told him of my last visit here when I had continued on to the top of Garbh Meall at 3054ft, and its neighbouring Munro, to drop down into the Allt Conait for a walk into another superb fragment of Caledonian wood in Glen Lyon.

No county in Scotland offers such off-the-beaten-track scope for woodland and glen walkers as leafy Perthshire

A much easier way of linking Loch Rannoch to Glen Lyon is from Carie, the Lairig Chalbhath, but it has been spoiled for me by being turned into a Land-Rover track. Still, we were agreed that no county in Scotland offers such off-the-beaten-track scope for woodland and glen walkers as leafy Perthshire, for there are so many alternative ways through the hills and so many fine lochs. Pat had wider knowledge than me of the low and medium ground if I had the edge on the tops, so here was my chance to share his own special bits.

The first trip was to Glen Lochay, the “dead-end” glen at the head of Loch Tay which runs parallel to Glen Lyon and is walled by 3000-ft peaks of the Mamlorn Forest — which, of course, does not mean trees but deer forest. Motoring as far as we could go, to the locked gate, we were putting our bags on our backs when I heard the little talking sounds of the heather linnet, the twite.

“No, I’ve never seen them in this glen,” said Pat in disbelief, but there they were — a good omen.

Where was this track taking me?

“To Donnachadh Ban’s seat. I was told by well-informed folk in the glen that in the burn of the Allt Batavaim there was a stone which the great Gaelic poet would walk to from his house to think about a song. I looked for it, and I’m sure I’ve found it. See what you think.”

I hadn’t realised that Duncan Ban Maclntyre, greatest of all Gaelic bards, had lived for ten years in a house by the burnside when he was made forester to the Earl of Breadalbane after the 1745 Rising.

This was hallowed ground

For Pat, who loves all things Gaelic — he is one of the Duke of Atholl’s Eagle pipers — this was hallowed ground, and great was his excitement as he led me to the “seat”.

“It’s a natural armchair, shaped and smoothed by the bum when its course was much higher than it is now.”

I think Duncan would have approved of the tall figure in the faded green kilt, heather tweed jacket on his shoulders, un-ornamented dirk in his stockings, and hob-nailed hill boots on his feet. And in tribute to Duncan he had brought along the book of his poems and proceeded to recite one of them in the Gaelic, the music of the words lingering on his tongue.

Then on and up we went by the edge of a waterfall in a scent of rowan flourish, climbing up to a pass crossing easily between Creag Mhor and Beinn Heasgarnich, a route to Bridge of Orchy and Ben Dorain. Two families of shepherds lived over that north side of the pass the first time I climbed these two hills. Now their homes are below the waters of a reservoir impounded by a 1740-ft length of concrete dam, and the former right of way path has disappeared for ever.

“Fair Duncan of the Songs” would have needed all his poetic skill to describe the earth and water moving changes which have taken place in Glen Lochay and Glen Lyon since his day, with the waters of the first being conveyed to the second by aqueduct, then, after use in a power station, being returned to Glen Lochay Power Station by another aqueduct in what seems a mix-up of pipes, pylons and concrete dams, producing 160 million units of electricity.

Much of the natural and the beautiful remain

But the bard would be heartened to find that it has been done with the minimum impact on the environment, for so much of the natural and the beautiful remain, as I now know – after another few visits with Pat. Having seen so much, I can now declare my favourite spot to be Corrycharmaig, named after St Cormac, who had a chapel on Loch Tayside called Cill Mo-Charmaig.

The River Dochart which flows below Ben More and makes such a white cascade over the rocks at Killin has its source on Ben Lui above Tyndrum, and is, in fact, the infant Tav. And it was the route of the old Oban railway, which climbed up Glen Ogle from Callander before swinging west for Crianlarich. It was by train on this line that both of us in our different ways first explored Perthshire. Indeed, by an accident of snow and ice blocking the roads in February 1965, I took the train from Stirling to Strathyre, little realising it would be my last journey for the line was closed the following September by a landslide of boulders in Glen Ogle.

A fine stretch of the line, including the bouldery bit that was blocked, had now been opened for walkers. It begins at Lochearnhead with a grassy climb just beyond the hotel, where a map is posted explaining the route, three miles up to the top of Glen Ogle, then back by a delightful old road. We walked it, and enjoyed seeing the line stonework of embankments and the great viaduct over a ravine.

We then went by car up Lubnaig-side where even more facilities for enjoyment have been laid on this summer. A new car park above the Falls of Leny, attractive picnic and sunbathing spots on the waterside, and a splendid Information Centre at Strathyre.

The last corkscrew took us over the bridge to Balquhidder

This is where we turned off, over the old bridge by the timber chalets, then hard right at the T-junction on a single-track contour along the River Balvag in an attractive green strath, its cattle grazings hemmed by steep spruce forest whose darkness is offset by the natural oaks and birches hemming the twisting road. The last corkscrew took us over the bridge to Balquhidder and the kirk-yard where Rob Roy and his wife lie buried.

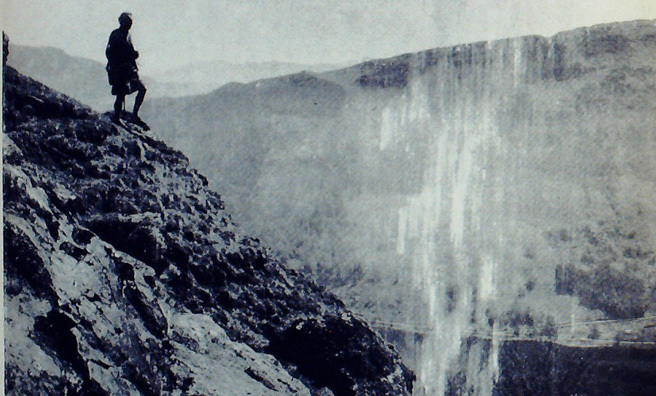

Then we went west for just over a mile to the steep gully of the Tulloch Burn, where I was promised a look into a secret cave high above.

And there it is in a narrow, rocky place with a waterfall.

I dashed through, to look out through a sparkling curtain of fragmented water drops to Loch Voil

“That’s it,” said Pat with a flourish. “You’ve got to get wet if you want to go in.” I dashed through the fall, to look out from the deep recess through a sparkling curtain of fragmented water drops to Loch Voil far below. Pat had never been right inside, and was greatly surprised at the amount of room at the back where he could stand upright.

Now we took to the turfy grass runnel of an ancient peat road leading us to the hags which supplied the clansfolk with fuel, and in their wet blackness a herd of red deer were cooling off, scampering away before us as we climbed to the ridge at 2000 feet.

It was a place to linger

Our destination at the end of the ridge was drawing close, and suddenly over the next rise it lay below us, Lochan an Eireannaich, a dark oval overhung by, on its far side, a 200-ft thrust of grey rock known as “The Irishman’s Leap.” That lovely oasis of tranquillity is all the better for being almost on the crest of a pass at 1800ft, midway between Balquhidder and Luib in Glen Dochart. It was a place to linger in, having all the elements that one seeks — grandness, remoteness, peace. Scotland off the beaten track is still a wild place.

In one such place Pat showed me, later, a secret osprey eyrie. We were in luck on our visit, for we had the first proof that it had nested successfully when the cock bird swung over the trees with a fish slung from one talon, delivered it to the hen, who stood with her mate on the rim to give us a marvellous view of their noble forms, ruffled white feathers of the crown, the very large eyes, the chocolate brown of mantle, snow-white underparts, every detail sharp at close range.

When the cock suddenly left, the moment of truth came as the hen tore off a few strips of fish and began reaching down into the cup of the nest in a food-passing gesture. We heard a little bit of squealing, too, probably the chicks squabbling. We have positive proof there are two, for which Pat and his friends can take some credit, for they have been watching and guarding these birds against egg thieves. They even put up the money with the help and permission of the Forestry Commission, while the RAF provided a helicopter to carry in the prefabricated sections of the hide in which we sat.

So all news is not bad news, not in Perthshire anyway.

Read more from Tom Weir next Friday.

- Above Loch Voil

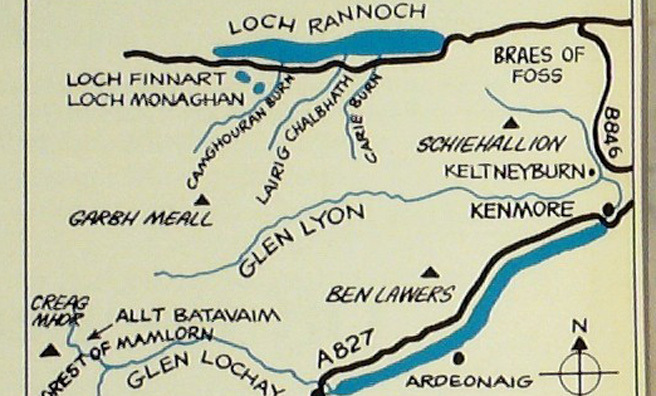

- A map of the area

- Above Glen Lochay

- A view from behind the waterfall to Loch Voil

- The shore of Loch Tay looking to Ben Lawers

More…

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archives of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly but surely getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here.