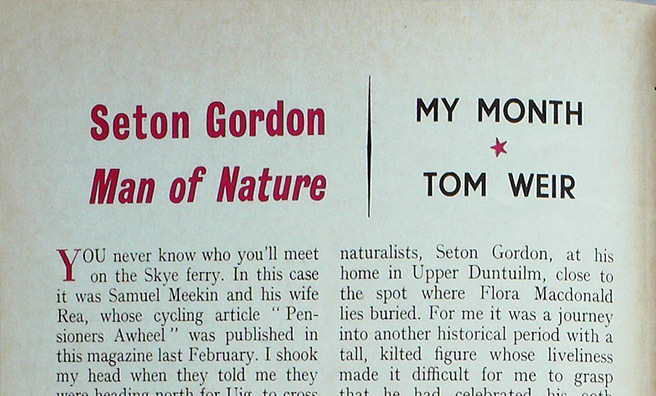

Tom Weir | Seton Gordon

In September of 1976 Tom Weir caught up with the doyen of Scottish naturalists, Seton Gordon

YOU never know who you’ll meet on the Skye ferry. In this case it was Samuel Meekin and his wife Rea, whose cycling article “Pensioners Awheel” was published in this magazine last February.

I shook my head when they told me they were heading north for Uig, to cross to Uist and cycle through the Outer Hebrides.

“I’ve done it once, and been blown to a standstill. The only good thing about cycling out there is that it’s great when you stop.”

Clearly, they thought I was joking.

“In fact, I’m a bit worried myself,” I told them. “For I’m meeting two pals at Uig who’ll be rounding Ardnamurchan now in a 36-ft. ketch, Mysie, and the theory is that I’ll join them tomorrow night for a birding trip to remote skerries. I think I’d rather be with you on the bike in Uist than out there on that sea if the weather keeps rough.”

I don’t know how Sam and Rea got on in Uist. But I didn’t expect to find the Mysie battened alongside Uig pier after a fierce day of wind and rain. The time was 6.30 p.m., and they had just got tied up and put the dinner on when they heard my shout.

“It was great,” enthused Graham, the skipper. “Rags of green water, lots of fun, real sailing.”

Iain, good in boats, admitted to feeling squeamish and having to take pills to stay on his feet.

The tales of Seton Gordon

I was glad I had opted to spend a more profitable 36 hours by motoring to Skye, and driving north from Uig to talk to that doyen of Scottish naturalists, Seton Gordon, at his home in Upper Duntuilm, close to the spot where Flora Macdonald lies buried.

For me it was a journey into another historical period with a tall, kilted figure whose liveliness made it difficult for me to grasp that he had celebrated his 90th birthday on April 11 this year.

“Show him the photographs,” smiled Betty, his wife. “That’s my son—he builds houses in Canada, and came over from Vancouver for the birthday party. That’s my daughter who lives at Dunsyre. I have a daughter in Australia, but it was too far for her to come. With the grandchildren, it was quite a family gathering.”

Then, as we sat down to talk, he said, “The last time we met was in Edinburgh. You gave a lecture, and I played Farewell to St Hilda on the pipes. We were fund-raising for the National Trust.”

At which I could only reply, “And twenty years later you are still hanging on to your own teeth and looking remarkably unchanged. Are you still playing the pipes?”

“I still have a blow,” he chuckled. “They are in Portree getting a new bag put on. Angus MacPherson of Invershin, who died in April this year, would have been 99 in July if he had lived. He played until he was 97, which is the record I have to beat. He was the last of the old type of pipers who put the soul of the tune above all. Finger- work is not enough.

To go by the book is to have technique without expression. Piping is in a state of flux. People are all fingers. You have to put away the book to realise the music and the beauty of the tune.

“Without the pleasure of piping and judging at competitions my life would just not have been the same.”

Snow blizzard in the Lairig Ghru

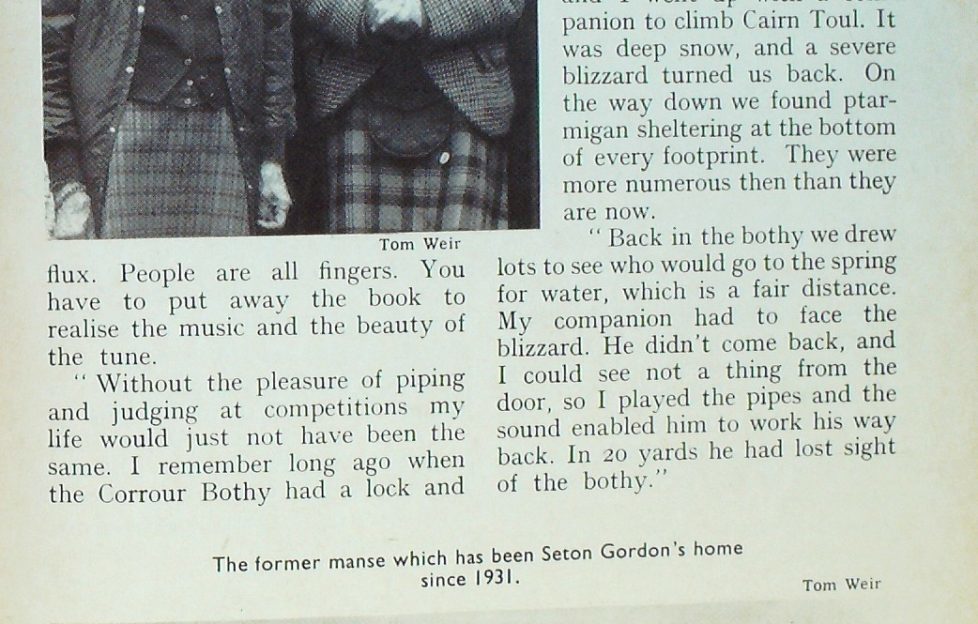

“I remember long ago when the Corrour Bothy had a lock and I had a key.

“It was December, and I went up with a companion to climb Cairn Toul. It was deep snow, and a severe blizzard turned us back.

“On the way down we found ptarmigan sheltering at the bottom of every footprint. They were more numerous then than they are now.

“Back in the bothy we drew lots to see who would go to the spring for water, which is a fair distance. My companion had to face the blizzard. He didn’t come back, and I could see not a thing from the door, so I played the pipes and the sound enabled him to work his way back. In 20 yards he had lost sight of the bothy.”

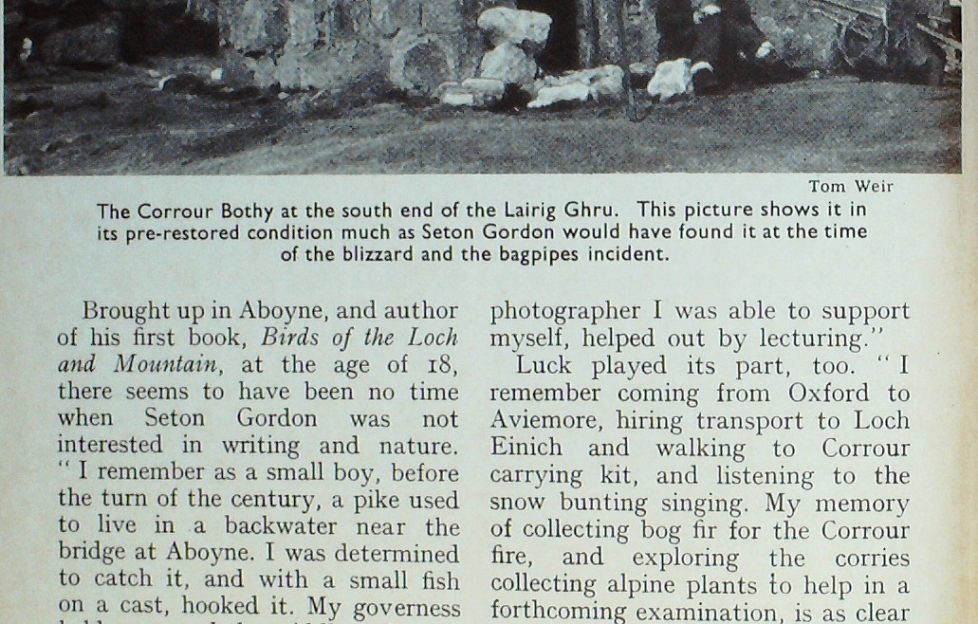

Brought up in Aboyne, and author of his first book, Birds of the Loch and Mountain, at the age of 18, there seems to have been no time when Seton Gordon was not interested in writing and nature.

“I remember as a small boy, before the turn of the century, a pike used to live in a backwater near the bridge at Aboyne. I was determined to catch it, and with a small fish on a cast, hooked it. My governess held me round the middle and went backwards with me as I drew it in. Lord Huntly happened along just as I got it ashore, and couldn’t believe such a small boy had caught a seven-pound fish.”

I asked about his writing. The only thing his memory was weak on was the exact number of books he has written.

“Twenty-nine, I think. For me, writing has always been 99-per-cent, pleasure. I think I got it from my mother, who was sometimes called ‘ the Queen’s poetess.’ As an author and nature photographer I was able to support myself, helped out by lecturing.”

Luck played its part, too.

“I remember coming from Oxford to Aviemore, hiring transport to Loch Einich and walking to Corrour carrying kit, and listening to the snow bunting singing. My memory of collecting bog fir for the Corrour fire, and exploring the corries collecting alpine plants to help in a forthcoming examination, is as clear as if it happened yesterday.”

Back at Oxford the luck came when the question on his examination paper read,

“Write all you know about alpine botany.”

His detailed answer gave him the distinction of being the first student at Oxford to get an honours degree in botany through writing of the alpine flora of the Cairngorms.

Forging a career in botany

“My idea was to get a job with the Board of Agriculture. I took a diploma in forestry, and an honours degree in natural science, but didn’t get the job.

“I went to Russia in 1912 with Prince Felix Youssoupoff. He was with me at Oxford; he owned 32 properties and wanted me to be one of his foresters. He was the Prince who killed Rasputin and married the Czar’s niece, and if I had taken the job I might have died in the Revolution.”

Instead, the outbreak of war in 1914 found him planning to join in the action by driving an ambulance. Then out of the blue came the offer of a job organising a secret coast-guard service under the guise of being a travelling birdwatcher. Based on Mull, and with his own fishing boat, Lustye Gem, a whole new world opened up as he got to know the Inner Hebrides while watching out for enemy submarines.

“It seemed all wrong that I had this marvellous chance to go where I pleased, landing on uninhabited islands and enjoying wild life, while friends were being killed in France.”

Married in 1915 to Audrey, who was to be a tower of strength to him for 44 years, he had no doubt that his two years at Ardura from 1914 to 1916 were the happiest of his life.

“I don’t think anybody ever got to know Mull so well. And even although I’m a bad sailor, I enjoyed the freedom of that boat to go anywhere.”

Then came a move to Aultbea as Naval Centre Officer, and here he met 8o-year-old Osgood Mackenzie and helped him write one of the classic books of this century, A Hundred Years in the Highlands.

“Osgood was so thrilled, like a boy, with the book, that he began writing another. He died as he was writing. I can’t really say I got to know him, for the gap in our ages was too great. He had no use for English, and his wife left him because he would speak nothing but Gaelic.”

At this point Mrs Gordon came in to ask us through to lunch, and now I had a real chance to speak to her, for she had tactfully stayed out of the way to let us get on with our talk.

“Betty was a great friend of ours before my wife died in 1959,” Seton Gordon had confided.

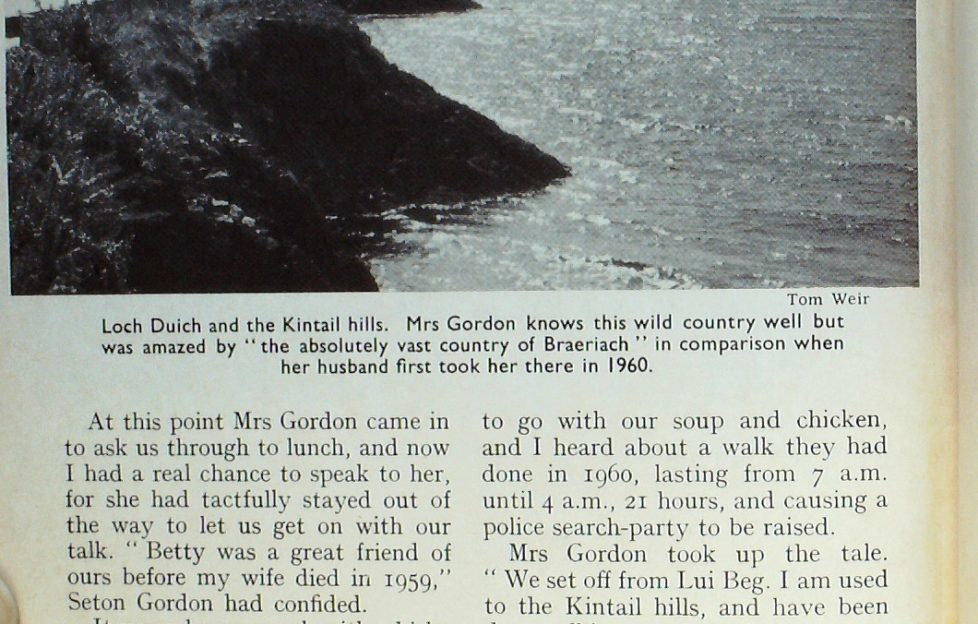

It was a happy meal, with whisky to go with our soup and chicken, and I heard about a walk they had done in 1960, lasting from 7 a.m. until 4 a.m., 21 hours, and causing a police search-party to be raised.

Mrs Gordon took up the tale.

“We set off from Lui Beg. I am used to the Kintail hills, and have been deer-stalking in them for 22 years, but it was my first time in the absolutely vast country of Braeriach, so rough with stones. The real surprise to me was to find the whole summit pink with flowers of Silene acaulis, growing from gravel. We saw ptarmigan with young, and a red deer hind with a spotted calf …”

Recollection stirred Seton Gordon.

“I’ll never forget the richness of colouring as the sun went down, intensifying the blaze of red from the flowers. I’ve never seen anything like it. Ben Nevis was clear. So were Cruachan and the Glencoe peaks.”

As he talked, I made a small calculation in my mind, that he would be 74 when he saw that sight on the remotest top in the Cairngorms.

Also, that 50 years earlier he had written the Cairngorm Hills of Scotland, which was one of the first mountain books I read as a teenager, gripped by climbing and wildlife. It profoundly influenced my own desire to see these things and write about them when I grew up.

The memory of that visit to Braeriach sparked off another

“I remember going every day to the Wells of Dee to get the incubation period of the dotterel at 4000 feet, in 26 days the dotterel got to know me, and as I watched on one occasion a daddy-long-legs landed on my arm. The dotterel ran to my sleeve, swallowed it, and instead of flying away, gazed into my face steadily, then went back to the eggs. I felt I had been recognised as a friend. But if my collie got up from where it was lying the dotterel would do the broken-wing trick.

“I recall one day of showers when the eggs were chipping and a storm of hail was battering the hill, when the bird came running to the nest at top speed and looked up as it covered the eggs as if to say, ‘Just got back in time.’ It got them all off safely.”

With such a love of the high Cairngorms and the ancient Caledonian pines of its glens, I asked him how he came to choose a headland as bare as Upper Duntuilm in Skye as a permanent home.

“We came here in 1931. The house had originally been the manse and has 70 acres of croftland. We liked the place. I could write, and my wife worked the land. We had eight or nine cows, some sheep. We grew oats and potatoes. There were men in those days to cut peats. We planted the shelter belt round the house.”

I asked about his working discipline.

“Six hours writing a day was my usual, three in the morning, off in the afternoon, then another three hours after tea. The roads were quieter in these days and travelling was easier. A car was essential. I used to go lecturing during February and March, travelling all over Scotland, Ireland and England. At the Royal Institution I was the only nature man to be exclusively honoured.

“I always showed my own slides, taken with a half-plate camera. You had to be strong to be a nature photographer in the old days, everything was so big and heavy for the distance you had to carry it. I always finished my lectures so as to be back at Duntuilm for the nesting of the golden eagle. It is four miles to the eyrie from here. I used to leave in the morning for the walk, sit for five or six hours, then home. The eagle didn’t mind.

“I saw the mating of the pair once. There was 20 inches of snow on the ground at the time—soft snow. The bird came straight down on the hen, pushing her out of sight as he mated her. Come through to my untidy study and I’ll show you some of the things I’ve collected over the years.”

It is not very often I meet my match for untidiness, but this was getting close to it—desk and tables covered in letters and papers, books everywhere, lively bird paintings on the walls and photographs jostling each other for room to show themselves on the ledges.

“My typewriter,” he smiled. “It’s a genuine antique, but still in use. I don’t do much real writing now, but I get a lot of correspondence from readers, and I always answer it.

Anecdotes flowed from him as we went round the walls, and here is a point I must make about Seton Gordon. He is a much more humorous man than is apparent in his writings.He is also a very good mimic, and I only wish I could tell some of the stories he asked me to keep secret in case of giving offence.

Tact and kindliness are built-in responses. Lairds in the old days, it would seem, were not only jealous of stray tourists, but of other lairds who might dare to walk over their property.

And on Deeside the situation was particularly critical . . .

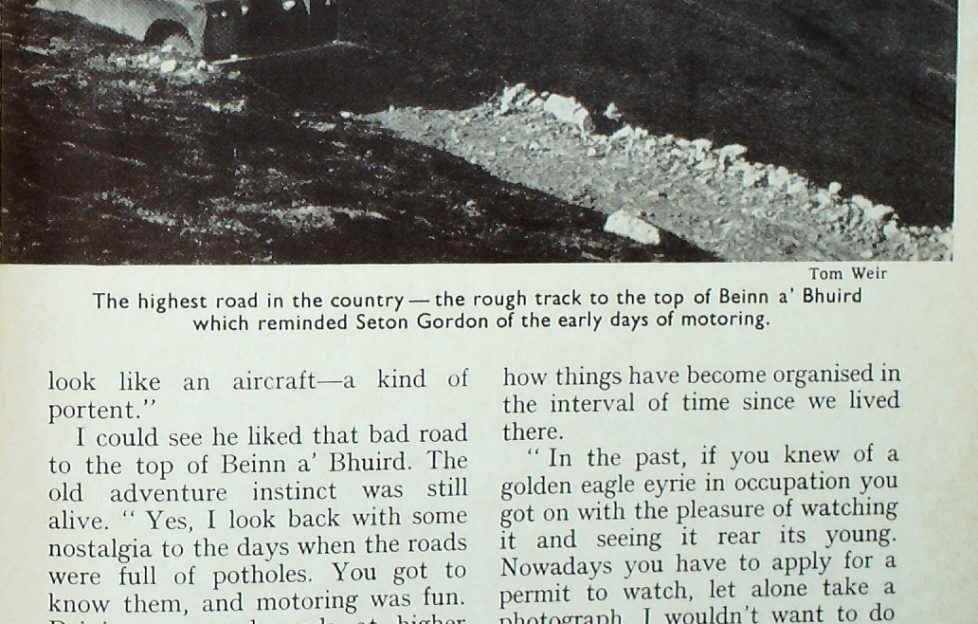

“At the beginning of the century, when Mar Lodge was really private, you could not cross Victoria Bridge to the Lodge without special permission. Now it is a hotel, and a jeep road goes almost to the top of Beinn a’ Bhuird.

“I’ve taken advantage of that road, too. I’ll tell you what we did when we were staying with Farquharson of Invercauld. We went to church in the morning at Crathie. Went home for lunch. Then drove to Mar Lodge, got the key of the lock on the gate, and drove off for the top of Beinn a’ Bhuird at 2.30. It’s a terrible drive, as I’m sure you know, but it got us up there so quickly there was time to walk over the tops and look at the snowfields. The sun was low, lighting the zig-zag shore of Loch Etchachan when we got back to the Land-Rover. It made the shore look like an aircraft—a kind of portent.”

I could see he liked that bad road to the top of Beinn a’ Bhuird. The old adventure instinct was still alive.

“Yes, I look back with some nostalgia to the days when the roads were full of potholes. You got to know them, and motoring was fun. Driving on good roads at higher speeds is actually more tiring. When I drive from Skye to Invercauld it seems such a long way, especially from Tomintoul to Braemar over the Lecht. I still enjoy driving, but I don’t like to go more than 40 miles an hour.”

We talked about Aviemore, where Seton Gordon and his wife Audrey had lived for 16 years, doing some of their best golden eagle work, spending no less than 167 hours in one season in a Speyside eyrie.

“Our old home is now the Nature Conservancy Office, which shows how things have become organised in the interval of time since we lived there.

“In the past, if you knew of a golden eagle eyrie in occupation you got on with the pleasure of watching it and seeing it rear its young. Nowadays you have to apply for a permit to watch, let alone take a photograph. I wouldn’t want to do it now.

“I think 75 per cent, of my enjoyment of the Highlands now is made up of memories, of times when you knew everyone, landowners, keepers, countryfolk. Wherever you went you stayed the night with friends — they would have been offended if you had done anything else.”

Inevitably, the world becomes a lonelier place when you grow old and outlive your contemporaries. I asked him how he felt about death.

“I feel it’s something to look forward to, for the people you have known and want to meet again. One believes in a future life because of one’s own experience. I am impressed by the goodness of people, and I believe in telepathy. I have felt it very strongly.

“There is less to do here at Duntuilm when you lose the strength to go long cross-country walks. You realise how terribly exposed to weather the headland is. My wife’s home is Biddlesdon, in Northamptonshire, and we winter there. She has a little house in Kintail where we stay, but I like to spend the summer here and take a walk every day. It is a wonderful place for sunsets.”

Seton Gordon would agree that life has been good to him, blessing him with exceptional health, a good brain and a creative imagination to use it. In terms of stick ability and sheer stamina in the field of natural history he has set an Olympic standard.

One of the great strengths of his writing is the strongly personal thread that runs through all of it. Few reference books are more valuable to a writer than his Highways and Byways in the Western Highlands and Highways and By-ways in the Central Highlands.

My problem in talking to Seton Gordon that long day as wind and rain beat upon the windows of his home was to keep the conversation oriented towards him and not on me. Then as I got up to go, I told him 1 was heading down to Uig to meet up with my sailing friends who should now have pushed their way up from Ardnamurchan.

He was intensely interested in our plans, and I could see the old coast-guard officer was envying us the option of the wide seas and the kind of landings on remote skerries he had made himself. Hut, being a bad sailor like me, he was appre¬hensive about the weather. We shook hands. It had been a grand day, but it was not quite goodbye to Mr and Mrs Seton Gordon.

Before breakfast next morning I would be sailing past Duntuilm in the Mysie and we were to meet again.

In the next instalment Tom Weir describes his sail in the Mysie amongst the Outer Hebrides

More from 1975

More from 1976

- September 1976: Seton Gordon, Man of Nature