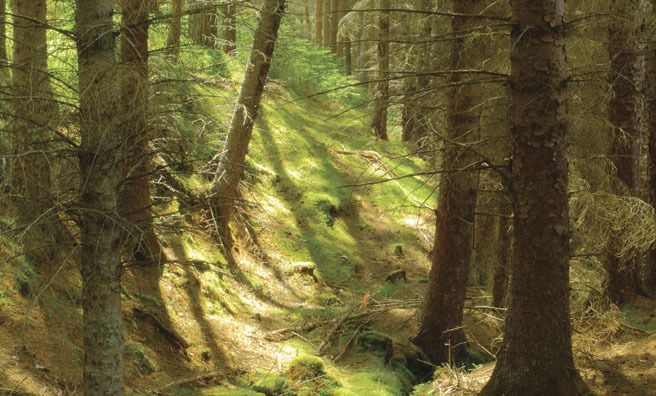

Woodland Wonders

In August pinewoods go all drowsy on me, flat-footed and weary like an old dog.

I know this trait of pinewoods of old. I have, after all, been here before.

I have evolved a philosophy about walking in pinewoods that crept up on me over decades of wandering and writing down the greater and lesser swathes of the Cairngorms, rather than something to which I heroically swore allegiance amid lightning bolts. It is that, seemingly involuntarily, I try to match my own mood to the mood of the pinewood. If the wood is bright and brave and spiced with resinous scents and birdsong, then that is the mood I bring to bear, all senses aflame.

This one has gone all drowsy on me

But the August pinewoods are rarely like that, and now this one has gone all drowsy on me. The mid-morning light is grey and suppressed, the air cool. The wind is quiet and listlessly astir in the canopy, just breathy enough to tremble the aspens (and aspens tremble at the least excuse). I think it is missing the presence of the mountains, as I am myself. On the bright, brave days there is a cluster of Munros vying to live up to the neighbouring glories of Ben Lui, but today they are cut off at the navel by the level floor of the cloud base. So this is part of what we used to call West Perthshire, but which is now (so the road signs say, at least) “the District of Stirling”. That huddle of grey roofs down there is Tyndrum, but today, in this mood, this pinewood could be anywhere at all, a deep-dark-green cloister taking refuge in a shroud.

I have been walking for about an hour now, half of which is the time it has taken to reach the wood from the car, following the track that tiptoes round an eerie, primitive horde of moraines and pools. I have stopped often to stare at that hummocky relic of the great ice’s last great gesture, that snail-trail spoor of the glacier that whittled down Ben Lui and the rest of its shrunken clan from Alpine heights, wrought Strath Fillan and Glen Dochart, and littered the place with deep, dark lochs. The pinewood is a latecomer in this company.

I see, hear, touch or smell, think my way into the mindset of the landscape

So on the days of pinewood drowsiness and half-mountains snuffed by the grey hood of fallen sky, I find I walk softer and slower, I look for the details that compensate for the absence of spectacle. I have no mechanism for going cheerfully when the landscape is so sombre, so I think more than I see, hear, touch or smell, think my way into the mindset of the landscape of hodden grey. Mostly it happens in midwinter or midsummer, and the only difference is the shade of grey (darker in midwinter) and the number of layers of clothing.

One consequence common to both seasons is that the greyer the day and the flatter the light, the more the pines themselves seem enriched. They glow. Their essential bottle-bluey-green deepens and shines so that at times it is as if they are rimmed in silver, like the leaves of alpine lady’s mantle.

That bizarre comparison occurs to me walking by the burn that pounds down the north edge of the pinewood through scattered stands of aspen clinging to rocky banks. There among the rocks are glittering silver-edged colonies of alpine lady’s mantle, and whenever the wind wanders in among them they flash their silvery undersides like a magic trick.

These are among my favourite wild flowers, although “flowers” is pushing every known definition of the word, stretching its very credibility. They do have flowers of a kind, tiny, dingy clusters on skinny stems, spots of yellow so feeble they are almost green, the whole concoction (to use an unbotanical term) quite unworthy of the spectacular foliage, a perfect silver-rimmed seven-leaf star and a thing of wonder.

At once all is changed

I turn for the trees at last, step inside their cathedral calm, and at once all is changed. The landscape becomes the pinewood itself, and all else is suddenly lost and irrelevant. A Scots pine in my mind, the characteristic wide-crowned shape, the rootedness in a mountain realm of heather and blueberry, the only tree to sustain golden eagle nests… all that is a kind of shorthand for Scotland. For that reason alone, I think the campaign to adopt it as our national tree is an inspired idea. An old mature wood like this one, even if it is still recovering from centuries of overgrazing, is one of Scotland’s wonders. Meet one on a day like this when the land is lost in its August drowse and feel it impose its calm on you, feel yourself succumbing to its pervasive stillness. And yet every moment you spend here you look expectantly past the next tree and the next for nature’s benevolent ambush.

There is a long, wide heathery slope that climbs at a gentle angle from the heart of the pinewood up to its western flank. No trees grow out on the slope so that it looks as if nature has created a parade ground for the staging of great events. A small army of people could march up there 20 or 30 abreast. I have come to a conspicuous birch near the foot of the slope, and collided head-on with an old memory, an old August, the evening sunny and warm, the heather at its purplest, and I leaned against this very birch to drink in the atmosphere, and just to linger.

After a while a red deer stag stepped from the trees, walked out into the middle of the slope and turned at right angles and started walking uphill towards the skyline. His condition was prime. His coat was glossy, his head was high, his antlers ten-pointed and wide, and his feet kicked up tiny clouds of purple dust from the heather. Then a second stag appeared, following, made the same turn at the same place so now there were two stags heading for the skyline. Then a third, then one at a time and several seconds apart, there came 15 more. They walked in single file at a quiet, measured pace until the first stag was almost at the skyline. Then he stopped.

I could hear the muffled thud of restless feet

The others walked up to him and stopped too, not in single file now but tightly bunched and suddenly nervous. There was a lot of movement in the group, but it remained tightly gathered. I could hear the muffled thud of restless feet on the hard, dry ground, the occasional rasp of antlers touching. Then in the gap in the trees and directly over the stags’ heads the silhouette of a golden eagle appeared. It circled once beyond the stags then came in low. The herd scattered and ran. The eagle charged down the slope not six feet off the ground then suddenly appeared to stand on its tail and soared vertically for two or three hundred feet, banked high above the trees and headed west whence it had come. Not one stag showed on the open ground.

“And what was that all about?” I muttered to the tree where I leaned.

I have heard of eagles charging deer, usually to try to drive them over a cliff, and seen one memorable film clip of such an incident in the Cairngorms, but there is no cliff here. These were all mature stags and far beyond the hunting ambitions of an eagle. It would take a wolf to bring one down. But the eagle knew that. It also knew that safety for the deer was only 20 yards away to left or right over easy ground.

So what was the point? Was there a message for the deer: I am a threat and in the right circumstances I can drive you over a cliff and kill you, so be fearful of me and vigilant at all times?

Was it making mischief? Was it playing?

Or was it suffering from the same mid-August torpor as I am myself on the kind of day when the heavy-liddedness of the weary old season slows my walking to a dawdle? But being an eagle rather than a more-or-less powerless nature writer, the bird decided to create an event, to galvanise the wood, to bully one of its elements out of its lethargy in the hope that a chain reaction among the other tribes of the wood might restore something like the natural order?

I like that last possibility, although I have no biological evidence to suggest it might be the case.

- A Scots pine, Glen Lyon, Perth and Kinross (Pic: Alamy)

- A golden eagle (Pic: Alamy)

- A red deer stag (Pic: Thinkstock)

- Lady’s Mantle (Pic: Alamy)

- Scots Pine, Loch an Eilein (Pic: Alamy)

- Glenmore Forest, Cairngorms National Park (Pic: Shutterstock)

- Cairngorm pineforest (Pic: Alamy)

Forest facts

- Thousands of years ago the Highlands were covered in ancient pinewood trees known as the Caledonian Forest. Today only 1% of the original forest remains.

- Go to Loch Garten, Rothiemurchus, Glen Affric and Loch Maree to see remains of the ancient forest.

- Scotland’s forests comprise Scots pine, birch, aspen, rowan, oak and juniper.