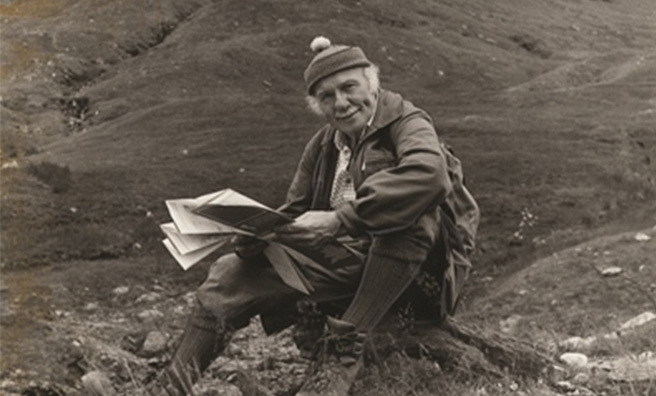

Tom Weir | West Highland Magic Part 2

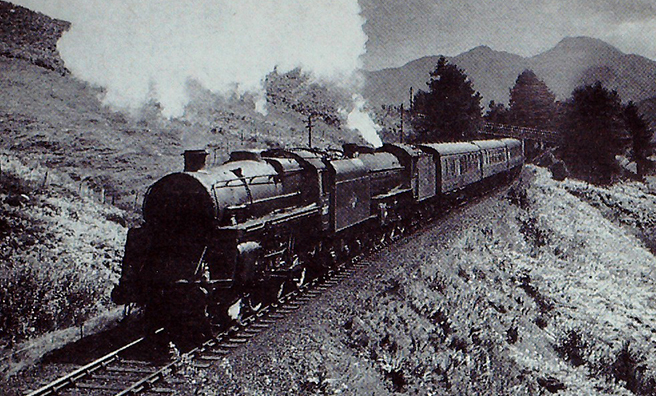

Tom Weir’s feature on discovering a “passport to wonder” through the West Highland Railway line, republished from a 1960s issue of The Scots Magazine

Click here for part one

The West Highland Line became my escape route, by Sunday excursion trains which took me to Arrochar, Crianlarich, or Bridge of Orchy at prices ranging from 1s 9d to 2s 3d, half fare, for I was small for my 16 years and able to turn the liability to financial advantage.

And it was thanks to these excursion trains that I found two of my best climbing companions.

The first was John MacNair, and I met him near the top of Beinn Ime. Neatly dressed in plus-fours and carrying a shepherd’s crook, he was coming off the top as I went up. To me he was a middle-aged man.

To him, aged 26, I was a very young boy to be on a mountain top.

We exchanged “Aye-Aye,” and when I told him I had just been over The Cobbler and Beinn Narnain and was returning on the excursion train that evening, he advised going to the top and he would wait for me and accompany me down.

John had me green with envy, for he lived at Arrochar, worked on the railway, and spent all his spare time climbing. And, thanks to “free passes,” he seemed to have been everywhere in Scotland.

Forthwith we fixed up a climb for another Sunday, and before that first climb of ours was over we had arranged to spend the third week of August in Torridon.

This holiday is still suffused with a happy glow in my memory, as one sunny day followed another and all the peaks of our desire fell below our bootheels.

And it was that same year, on the way to Tyndrum to climb Ben Lui, that I met Matt Forrester, a red-haired youth of 19, who had travelled up on the Sunday excursion train but was staying over until Monday, for it was a holiday week-end.

I expressed envy, at which he said, “I’ve plenty of grub for the pair of us if you want to stay, and I’ve a couple of blankets. The tent holds two.”

It did, and that was the beginning of a friendship which began with seven “Munros” and was to take us over most of Scotland.

Our first act of faith was to put our money together to buy a rope, and I have it yet.

Matt and I reckoned we knew most of the outdoor men in Scotland, for in these days of the early thirties few ordinary working men owned motor cars.

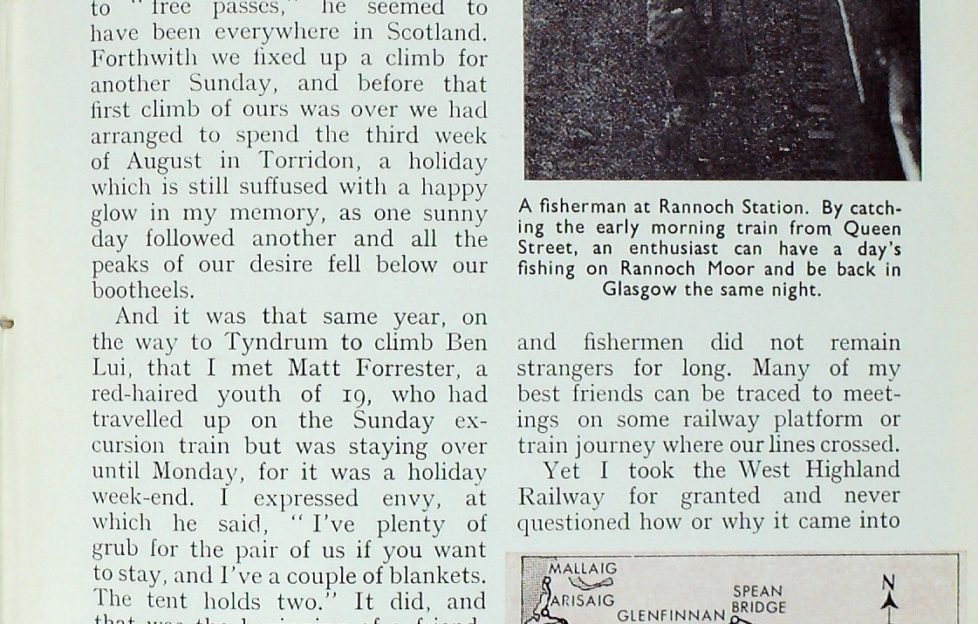

But an increasing tide of them were taking to the hills, so the excursion trains provided a great meeting point, and climbers and fishermen did not remain strangers for long.

Many of my best friends can be traced to meetings on some railway platform or train journey where our lines crossed.

Yet I took the West Highland Railway for granted and never questioned how or why it came into being. So far as I was concerned it had always been there.

It did not occur to me to query why it took its particular route by Loch Long and Glen Douglas to Crianlarich, and not by way of Strathblane, Drymen, Rowardennan, and Inversnaid, Glen Coe and across Loch Leven by a bridge at Ballachulish as was first proposed in 1884.

Read the next excerpt from Tom Weir’s

“West Highland Magic” online next Friday!

- Zoom-in for carousel. Scots Mag copyright.