Tom Weir | The Walker’s Wonderland

Tom Weir concludes his two-part portrait of Loch Lomond with visits to lesser-known features that can be reached on foot – and a dramatic tale of canoeing on its changeable waters

ABOUT Loch Lomond I can claim one unwanted distraction. I know it from within as well as without, for with a friend, I’ve been overturned in the 600ft-deep middle stretch between Rowardennan and Inverbeg, clinging desperately to an upside-down canoe and buffeted by a June north-easter.

The story, which happened about 20 years ago, could be called “How to Lose £250 of Cameras,” and I would have left them ashore had I known then that the easterly airt is the dangerous one for canoeing on Loch Lomond. My companion had just told me to stop worrying about the squalls that were rocking the canoe, when an arrowhead of advancing rain and wind struck. I remember the canoe sliding into a trough, being lifted on to the crest of a wave, and then neatly turning over.

There was not much hope of our cries being heard

There was no time for fear as I strove to break free from a canoe which was holding me like a cork in a bottle. I had the strange vision of being in a dream, watching myself drown when my body was suddenly released and I felt myself going down and down into darkness. Again I had the feeling of seeing myself as on film turning over in the water like a seal in a tank and breaking through a greenish roof into daylight.

In front of me was the upside-down canoe with my companion clinging to it, shouting my name. A few strokes and I was beside him, trying to get a grip as it spun awkwardly under our combined weight. “I was getting worried – you took a long time to come up,” he said, I said it must have been my camera bag jamming my knees against the deck, acting as a plug.

The loch was so choppy we felt hidden by the waves, nor had we much hope of our cries being heard. On the credit side, however, was the certainty that we must be cast up on the far shore of the loch if only we could hang on long enough.

After half an hour the cold was having a weakening effect on hands and arms. But we were lucky. We were spotted by two of our friends in single canoes. They came alongside and we transferred our grip from the over turned canoe to their sterns and were towed ashore by hard paddling.

To get warm, we ran up and down while our companions lit a bonfire on the beach. Clothing was wrung out, dry garments offered and a phone call was put in to Rowardennan to summon a vehicle to drive round the loch and take us back to the Youth Hostel.

This is what you call paying for your experience the hard way, and I felt lucky to have paid no more for it than a steep rise in insurance premium for the new cameras I’d bought. Our accident had occurred because neither of us possessed any practical experience of canoeing. My friend admitted afterwards that his knowledge was mainly theoretical.

Absolute calm can turn to dangerous choppiness very quickly

Just how dangerous is Loch Lomond to people in small boats? Well, just over a hundred years ago Sir James Colquhoun, fourth Baronet of Luss, went over to shoot fallow deer on Inchlonaig with his keepers. It was December, and the venison was to be distributed among the people of the village. At the end of the day, the loaded boat was seen passing Inchconnachan only a mile and a bit from home at Rossdhu, but neither the boat nor its occupants were ever seen again.

To form an opinion about Loch Lomond you have to be out in it in all weathers. I asked my friend John Groome, who for nine years has lived on the lonely Craig Rostan shore and has to depend on a boat to collect mail, provisions, fuel and other necessities of isolated living.

I’d say it is a wicked loch,” lie told me. “It looks O.K. until you try to cross. I’ve been in real danger many times. I’ve been lost for an hour in freezing fog, and it was not until I saw the lights of a car that I realised I was close inshore on the wrong side of the loch. I tried again, and found myself at Rowchoish, too far south — but at least I knew where I was. 1 was absolutely chilled when I got in. My boat now carries a compass.

” You get to know the wind channels. Absolute calm can turn to dangerous choppiness very quickly. The squalls come from both sides of the loch here, from the Loch Sloy glen, and from the ‘ windy glen ‘ over the shoulder of Ben Lomond. I pulled a young fool of a canoeist out of the loch the other day. He knew his canoe had a hole in it, but thought he could bale it quicker than it took in water. He discovered he was wrong when it sank. It was lucky for him I had decided to cross to Tar bet that evening. I heard his cries for help, and he was pretty exhausted when I got him aboard.”

Living in the wilds of Cuilness

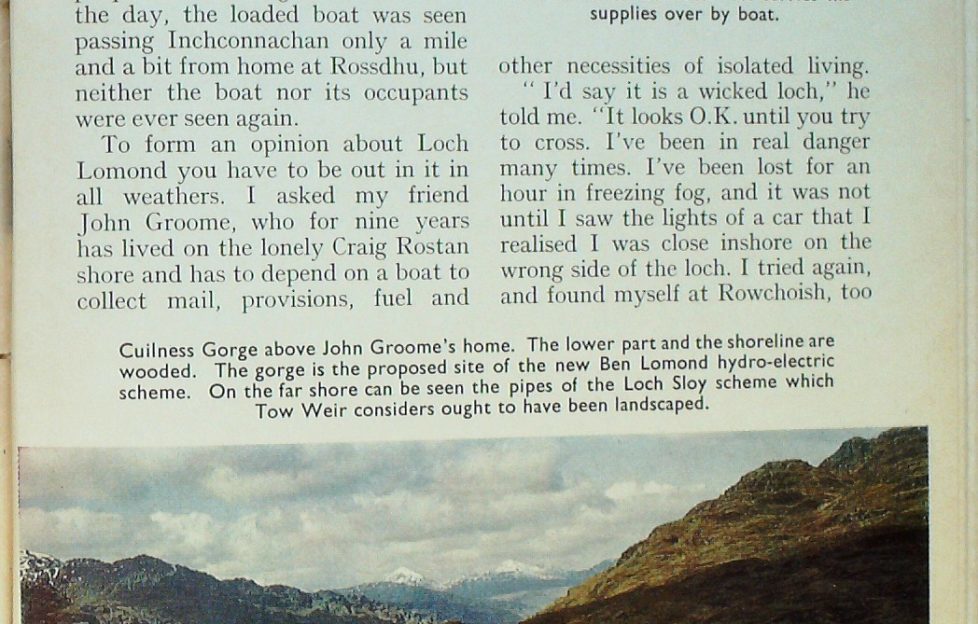

John lives at Cuilness beneath one of the finest wooded gorges in Scotland. Ever since I first explored along its edge, tramping in from Balmaha, its remote wildness has fascinated me. Let me try to crystallise a pre-war journey to it:

The month is May. It is nearly two o’clock in the morning and we have been tramping since 10 p.m. Marvellous at last to spread our sleeping bags under a sheltering rock on a grass shelf above the burn. Bliss to be here after the big effort of catching the last bus to Balmaha with a 10-hour working day in Glasgow shops behind us.

Later that morning wood-smoke and the smell of frying bacon brings me to pleasant consciousness. Around me I can hear a tinkling of willow warblers, the trills of wrens, the jangle of redstarts and the hum of a Gaelic song from Matt, in his element cooking over a wood fire.

“Aye, you’re awake, Tumsher,” he grins, pushing a plate of sizzling sausages arranged round a thick loin chop. (Matt was a butcher and brought nothing but the best.)

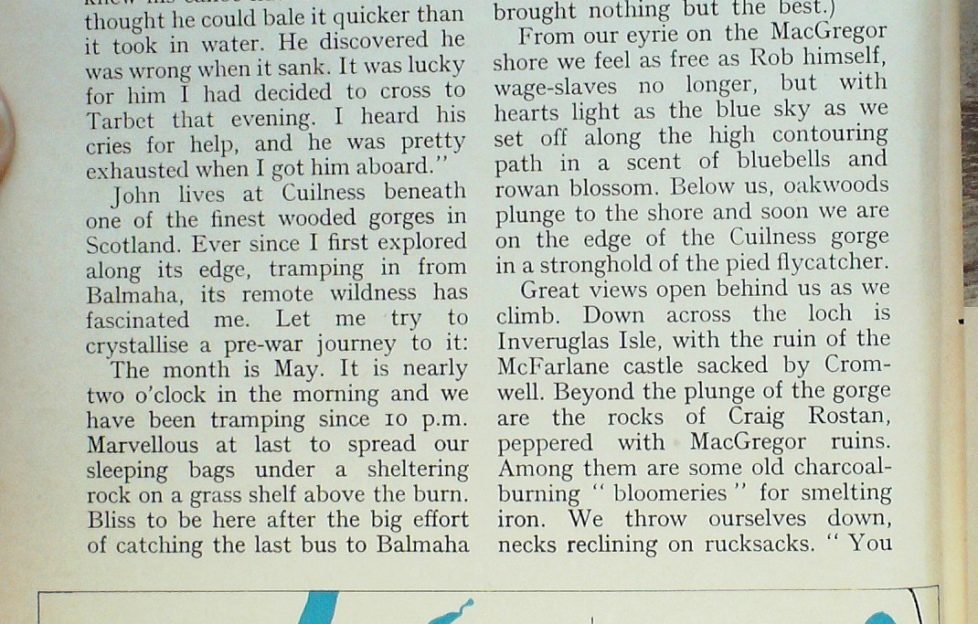

From our eyrie on the MacGregor shore we feel as free as Rob himself, wage-slaves no longer, but with hearts light as the blue sky as we set off along the high contouring path in a scent of bluebells and rowan blossom. Below us, oak woods plunge to the shore and soon we are on the edge of the Cuilness gorge in a stronghold of the pied flycatcher.

Great views open behind us as we climb. Down across the loch is Inveruglas Isle, with the ruin of the McFarlane castle sacked by Cromwell. Beyond the plunge of the gorge are the rocks of Craig Rostan, peppered with MacGregor ruins. Among them are some old charcoal- burning ” bloomeries ” for smelting iron. We throw ourselves down, necks reclining on rucksacks.

” You canny beat it,” says Matt as hee identifies the snow-veined peaks forming the headwall of Glen Falloch.

We can see the passes of the Lairig Arnan and the Dubh Eas which lead from Loch Lomond through to Loch Fyne, ancient cattle-droving routes which brought easy booty to the reiving MacGregors and McFarlanes, whose forays persisted long after they had died down in other parts of the Highlands.

The Government built a barracks at Inversnaid to contain Rob Roy, but he destroyed it before it could be completed—a far-seeing chief .

On again we strike east for the twisting north ridge of Ben Lomond, crossing a big, peaty hollow where red deer rise from the hags and race for a rock outcrop to stand in elegant grace looking down on us.

Threats to the natural world

This remotest bit of the Ben is, alas, coveted by hydro-electric engineers, who see in it a site for a reservoir. The plan is to build a big wall of concrete to seal the hollow so that water can be pumped 1200 feet from Loch Lomond into it. As on Ben Cruachan, the water could then be brought down to an underground power-house to make it one of the largest pumped storage schemes in the world, providing up to 2000 megawatts of electricity in its finished form.

We revel in the totality of the natural world around us as we dump our bags on the Cruinn a’ Bheinn- Ben Lomond col, and fairly dance up the airy ridge curving to the top of the most southerly Munro in Scotland.

The view is all we hoped for. Yonder, Ailsa Craig and the “Sleeping Warrior” of Arran, with, behind it, the dark outline of the Antrim coast from whence came the Celts who gave Scotland its name. Below us is the dark corrie of the Ben, with a wee burn tumbling out of it—the beginning of the River Forth. Its course is signposted for us by the crag of Stirling Castle and the chemical retorts of Grangemouth where it reaches the sea. Westward lie Jura and Mull.

From up here we can see clearly how man had such easy access to the Highlands from the Firth of Clyde, with Loch Long threading inland for 16 miles to end below the rock prongs of the Cobbler, an invitation to the Vikings to sail in, haul their longships two miles overland from Arrochar to Tarbet, relaunch in Loch Lomond and sack the shore and island settlements. Nor did they have to retrace to Loch Long after their raids, since they could navigate down the Leven, regain the Clyde below Dumbarton Rock, and join the main licet for the Battle of Largs where retribution was meted out to them.

It would be illuminating to know what the human population around Loch Lomond was like in those Viking times. It would be even more so if we could look back another 5000 years to the sight that met the eyes of the first Stone Age men to paddle their dug-out canoes on the loch, bows and arrows at flic ready, against human enemies or dangerous animals.

Perhaps these Baltic colonists numbered only a few dozen. Certainly they settled at Balmaha, at Luss and at Inchlonaig as we know from the stone tools they left behind. Probing forward would be a cautious affair, with 27.45 square miles of water and 3-5 islands to explore. The woods would be dangerous, with brown bears roaming, and wolves preying on elk and reindeer. The tree-line would be much higher than we know now, and the red deer would be larger and more heavily-antlered animals than those of today.

The geology of Loch Lomond

Why is Loch Lomond so narrow and ravine-like in the north and so wide at its southern base? The answer is in the rock structure. The unyielding Highland schists would not be pushed apart, so the compressed and moving mass of ice dug deep since it couldn’t expand. This is why the bed of the loch is 600 feet below sea-level between Tarbet and Inversnaid. But when the 2000 feet thick bull-dozer of ice got to Ross Point it met softer rocks and was able to push them aside and spread out. The islands of the south, which are the glory of Loch Lomond, are the gritty masses which withstood the passage of the ice.

One fish reflects the ice-age past, the powan, called the freshwater herring because it looks so much like one. The theory is that this plankton- eating white fish was forced to adapt to a freshwater existence when the land level rose with the removal of the great weight of ice as it melted. Thus, when the salt water hollow of Loch Lomond became fresh the powan adapted to its new way of life by spawning in the part of the year closest to Arctic conditions— midwinter.

Powan are the commonest fish in the loch and are good to eat when freshly caught, but to get them you have to use a net since, being plankton eaters, they rarely accept a fishing line. Pike, on the other hand, give good sport, the British record being a Loch Lomond fish that weighed 47 lb. n oz. The roach reaches its northern limit here, but for the game fisherman the real challenge are the salmon and pink-fleshed sea trout which enter the streams from the loch to spawn.

No other Scottish loch can list so many species of fish as Loch Lomond with sea lamprey, lampern, brook lamprey, brook trout, minnow, perch, loach, eel, three-spined and ten-spined stickleback, roach and flounder. Small wonder that the odd individual has been able to support himself on catches from the loch.

The best views in Scotland

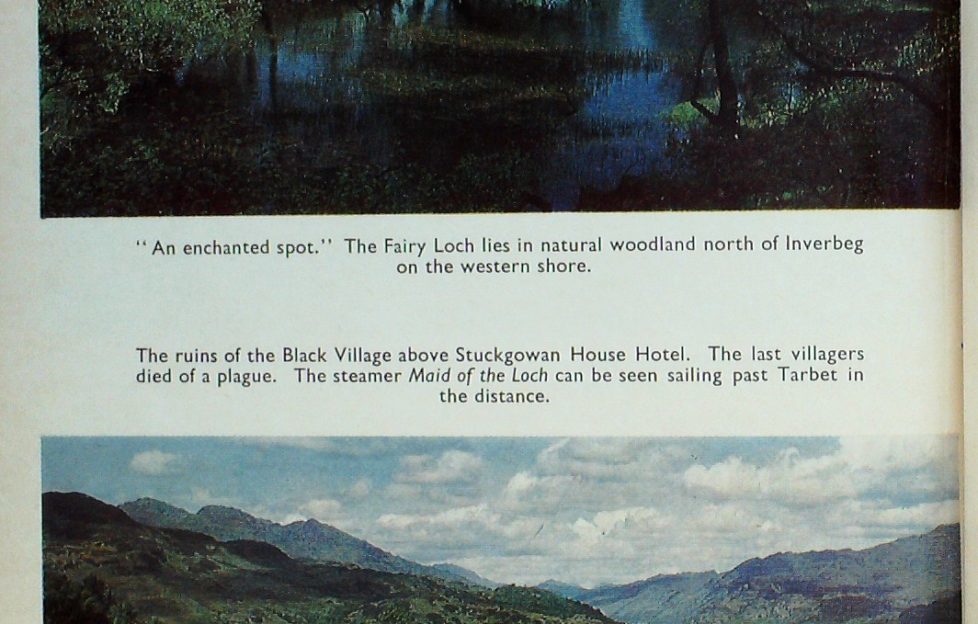

One of the special pleasures of living on Lomondside is that there is no end to discovery. Look at the colour photograph of the Fairy Loch. How many people have been to this enchanted spot, easily visited from a roadside ruin a mile north of Inverbeg ? After a steep climb up the burn you enter a reedy recess with a lochan so enchantingly beautiful that you can almost believe the story that the fairies put their special dye into it.

Or what about the Black Village on the steep hillside above Stuckgowan House Hotel ? Follow the drystane dyke uphill then climb obliquely left where the dyke makes a right-angled turn. The ruins look across to the white house of Cuilness and the sharpest impression of Ben Lomond. The people who lived on this lovely shelf high above the loch died in a plague.

Motorists should take the chance of visiting Loch Sloy, by stopping-off at Inveruglas and asking for a permit to use the high-climbing hydro-electric road.

“Loch Sloy ” was the war cry of the McFarlanes, and their pipe tune was appropriate to them, Togail nam Bo — the lifting of cattle. The rocky corrie encircling the loch was their gathering place. This wild clan were not mere reivers, but took honours at Flodden, at Pinkie, and they saved the day at the Battle of Langside. Like the MacGregors their name was outlawed for a time. Some were exiled in Strath ‘Aan and took the name of Allan or MacAllan. According to Seton Gordon their descendants are still distinguished by their Highland courtesy.

Loch Sloy is in greater use today than at any time since it was built at the end of the war, and produces electricity seven days a week, not just at peak load. Up there, one inch of rain produces one million units of electricity as the water rushes through the mountain by tunnel to discharge to the power house through four big ugly pipes which should have been landscaped years ago. Ten years ago there was talk of converting it to a pumped storage system like Ben Cruachan, but, if the plans for Craig Rostan go ahead, we are to have two power schemes facing each other across the narrow loch.

I asked my friend John Groome to express his own feelings on the subject. He replied by showing me a poem :

I wonder if the day will come when man Will hesitate to spoil

The quiet places wherein people can Retreat from daily toil;

When they will think it vital to say, ” No ” To bureaucrats who scheme,

And leave a place where men like me can go

In peace, perchance to dream.

John did not write his poem from the standpoint of a selfish man who wants the Craig Rostan shore to himself. Far from it. He was a weekender himself until he retired from being an executive engineer in the Post Office in 1967 and found this place. Few men over 60 would have moved from Glasgow into a house badly in need of attention, since it meant hauling everything he needed across the loch by boat.

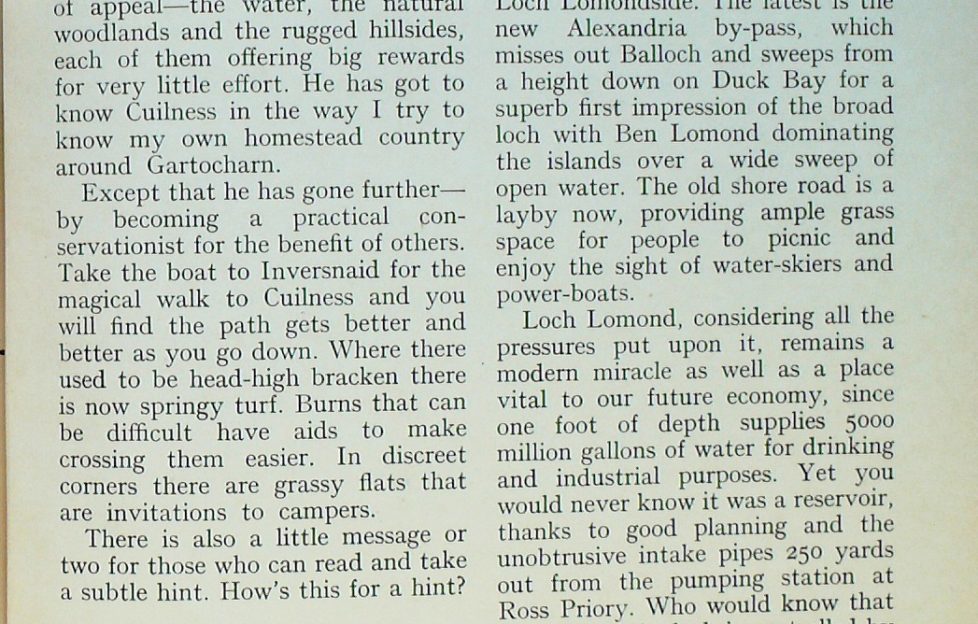

John would list his pleasures over the last nine years of retirement as having time to listen, look and observe the pattern of thee year in very beautiful spot with three levels of appeal—the water, the natural woodlands and the rugged hillsides, each of them offering big rewards for very little effort. He has got to know Cuilness in the way I try to know my own homestead country around Gartocharn.

Except that he has gone further— by becoming a practical conservationist for the benefit of others. Take the boat to Inversnaid for the magical walk to Cuilness and you will find the path gets better and better as you go down. Where there used to be head-high bracken there is now springy turf. Burns that can be difficult have aids to make crossing them easier. In discreet corners there are grassy flats that are invitations to campers.

There is also a little message or two for those who can read and take a subtle hint. How’s this for a hint?

Haggis conservation area.

Please close this gate.

And keep dogs under control in breeding season—

January — December.

Or this :

Let adders live

They keep down mice and Marauding dogs.

Another one says :

Pregnant ewes are Not used to youse. Be considerate.

A modern miracle

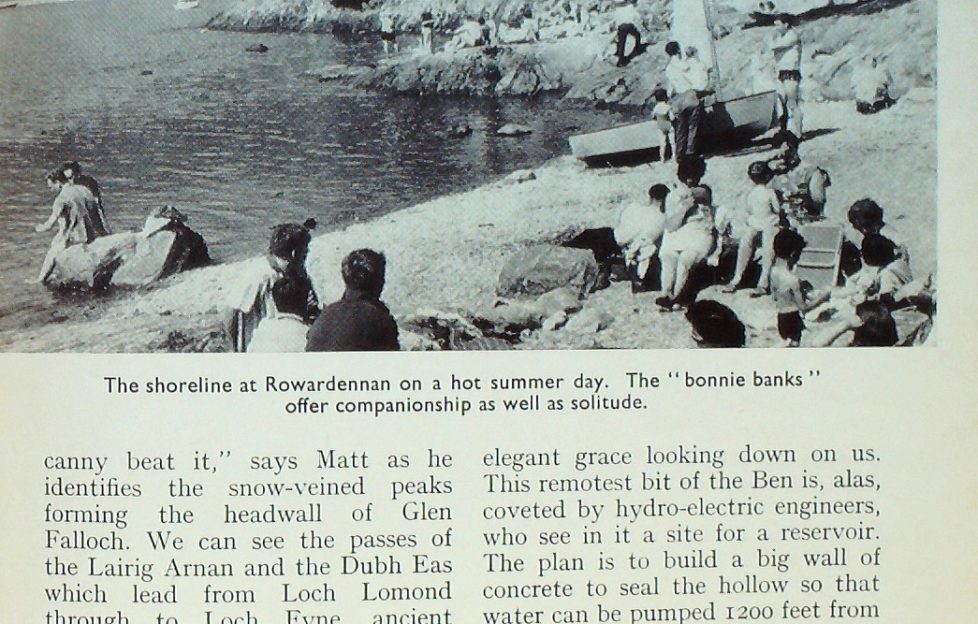

Changes go on all the time on Loch Lomondside. The latest is the new Alexandria by-pass, which misses out Balloch and sweeps from a height down on Duck Bay for a superb first impression of the broad loch with Ben Lomond dominating the islands over a wide sweep of open water.

The old shore road is a layby now, providing ample grass space for people to picnic and enjoy the sight of water-skiers and power-boats.

Loch Lomond, considering all the pressures put upon it, remains a modern miracle as well as a place vital to our future economy, since one foot of depth supplies 5000 million gallons of water for drinking and industrial purposes. Yet you would never know it was a reservoir, thanks to good planning and the unobtrusive intake pipes 250 yards out from the pumping station at Ross Priory. Who would know that the level of the loch is controlled by barrage gates on the Leven?

Today Loch Lomond is valued and used by more folk than ever before. Managing them is beyond the scope of the landowners. We have still to find the right balance between preservation, conservation and exploitation. At the end of the day the wondrous beauty of Loch Lomond is a public responsibility in which all of us must play a part.

You can read more of Tom Weir’s escapades here, where a new column is published online every Friday.

1975 Archives

1976 Archives

- August 1976: The Walkers’ Wonderland

More instalments every Friday