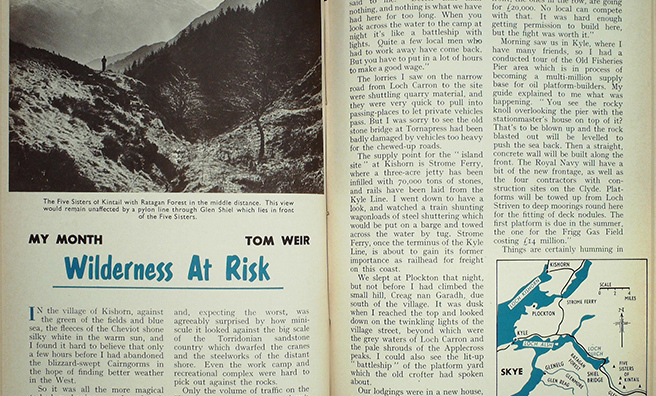

Tom Weir | Wilderness At Risk

In June, 1975, Tom was concerned about developments for a train line and marching

pylon route in South West Ross . . .

In the village of Kishorn, against the green of the fields and blue sea, the fleeces of the Cheviot shone silky white in the warm sun, and I found it hard to believe that only a few hours before I had abandoned the blizzard-swept Cairngorms in the hope of finding better weather in the West.

So it was all the more magical to be here, having proved my hunch correct, and looking across to little teuchat snow squalls trailing across the Applecross peaks. I had come to look at the big platform yard and, expecting the worst, was agreeably surprised by how miniscule it looked against the big scale of the Torridonian sandstone country which dwarfed the cranes and the steelworks of the distant shore. Even the work camp and recreational complex were hard to pick out against the rocks.

Only the volume of traffic on the Kishorn road and the thump-thump of pile-driving indicated that big things were afoot.

“The noise goes on all the time, but we think nothing of it,” one elderly resident said to me. “Better that than nothing, and nothing is what we have had here for too long. When you look across the water to the camp at night it’s like a battleship with lights. Quite a few local men who had to work away have come back. But you have to put in a lot of hours to make a good wage.”

The lorries I saw on the narrow road from Loch Carron to the site were shuttling quarry material, and they were very quick to pull into passing-places to let private vehicles pass. But I was sorry to see the old stone bridge at Tornapress had been badly damaged by vehicles too heavy for the chewed-up roads.

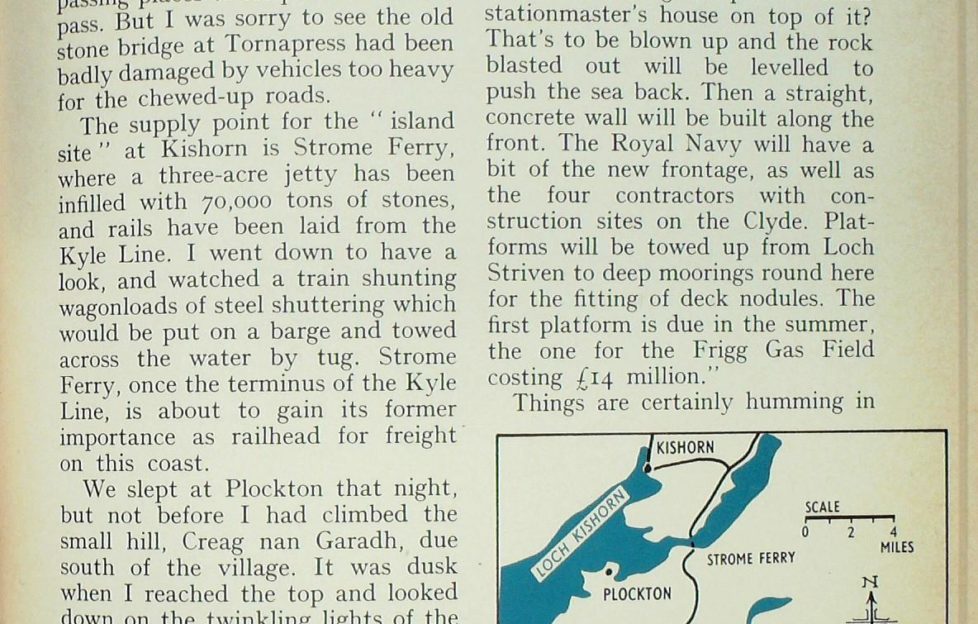

The supply point for the “island site” at Kishorn is Strome Ferry, where a three-acre jetty has been infilled with 70,000 tons of stones, and rails have been laid from the Kyle Line. I went down to have a look, and watched a train shunting wagonloads of steel shuttering which would be put on a barge and towed across the water by tug. Strome Ferry, once the terminus of the Kyle Line, is about to gain its former importance as railhead for freight on this coast.

We slept at Plockton that night, but not before I had climbed the small hill, Creag nan Garadh, due south of the village. It was dusk when I reached the top and looked down on the twinkling lights of the village street, beyond which were the grey waters of Loch Carron and the pale shrouds of the Applecross peaks. I could also see the lit-up “battleship” of the platform yard which the old crofter had spoken about.

Our lodgings were in a new house, superbly designed and finished by its owner, a local man.

“We had to build it, for any house going vacant here is snapped up by a ‘white settler.’ These houses on the village front, the ones in the row, are going for £20,000. No local can compete with that. It was hard enough getting permission to build here, but the fight was worth it.”

Morning saw us in Kyle, where I have many friends, so I had a conducted tour of the Old Fisheries Pier area which is in process of becoming a multi-million supply base for oil platform-builders. My guide explained to me what was happening.

“You see the rocky knoll overlooking the pier with the stationmaster’s house on top of it? That’s to be blown up and the rock blasted out will be levelled to push the sea back. Then a straight, concrete wall will be built along the front. The Royal Navy will have a bit of the new frontage, as well as the four contractors with construction sites on the Clyde. Platforms will be towed up from Loch Striven to deep moorings round here for the fitting of deck nodules. The first platform is due in the summer, the one for the Frigg Gas Field costing £14 million.”

Things are certainly humming in South-West Ross. Marconi have a base in Kyle, and a mini-submarine fixes instruments to the seabed for the navy, while work begins on the £65 million Ninian Platform at Kishorn, which is the biggest in the world under construction. Originally the Kishorn application was for a £130,000 development, but now that it has grown to a £5 million enterprise it is more in line with what was planned for Drumbuie.

Local folk take a realistic view of what has happened by saying: “The Government could have saved a lot of money and a lot of time by having the building yard at Drumbuie on the railway line. They would have saved millions.”

Yet the Kishorn choice seems to have pleased everyone, since it allows the Drumbuie crofting community to live in peace, and minimises the social impact of a large labour force on fragile communities by the remoteness of the camp. It has its own leisure centre, and a housing estate for staff workers is now being built as a natural extension to Strathcarron and at a scale suitable to the village.

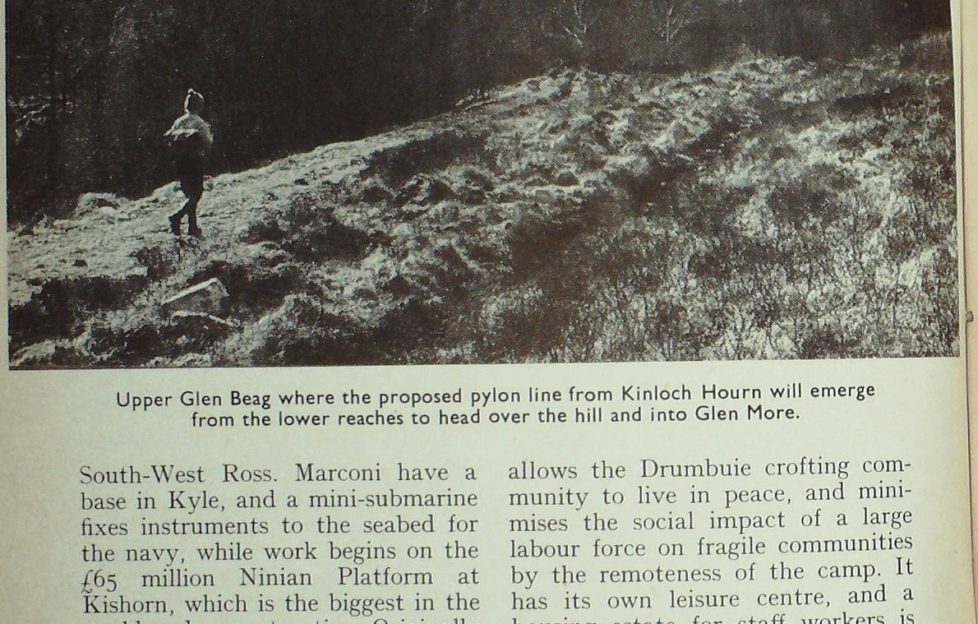

I think the way things are working out is fine. What I am disturbed about is the proposal to march a line of 73-ft. steel pylons by Kinloch Hourn to Skye when there are alternative routes that do not involve breaching one of the finest remaining fragments of wilderness left in Scotland. My own view was that any pylon line should follow the line of the Kyle railway from Grudie Bridge Power Station by the route of the present supply, but before I could form a definite opinion I decided to go on the ground of the Loch Hourn route and assess its scenic quality for myself.

So off we drove from Kyle to the head of Loch Duich, to swing up the zig-zags of the Ratagan Forest and drop into the trench of Glen More. As always, there was a fine feeling of arriving at one of the most pleasant backwaters of this whole coast as we came down to Glenelg, with its scatter of houses round the bay opposite Skye.

Remoteness for its own sake is part of the pleasure of Knoydart

No time to stand and stare if we were to walk the pylon route from the head of Glen Beag to the Bealach Aoidhdailean half-way to Kinloch Hourn by footpath. This bit was new ground to me, but I had a feeling of returning to old adventures, for I had once descended to that bealach from Ben Screel to push on to Kinloch Hourn and over the hill to Kinlochquoich. That was long before there was a hydroelectric scheme to power any pylon line, and the wee barn I slept in then is now below the waters of enlarged Loch Quoich.

So it was a great pleasure in six miles of walking to top the saddle of the narrow Allt Ghleann Aoidhdailean and look down on the scene of past climbs.

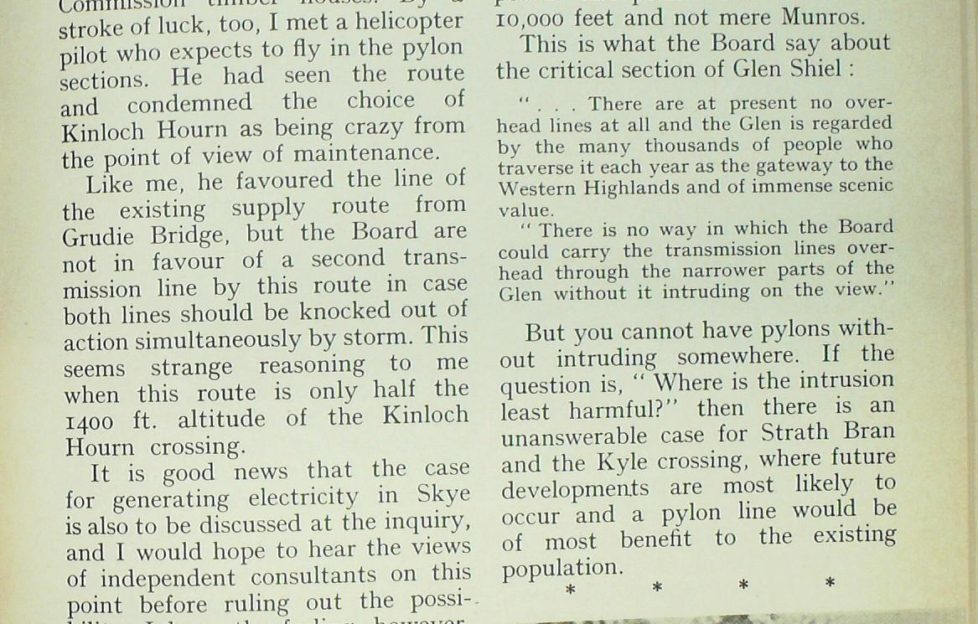

Remoteness for its own sake is part of the pleasure of Knoydart, but I would forego it if developments benefited the local people. But in this case the pylon line can have no local impact, for there is no population along the route until it get to Glenelg, and Glenelg already has electricity. The case the North of Scotland Hydro Electric Board make for the Kinloch Hourn route is that the pylon line would be seen by fewer people, and in distance it involves only 38 miles of construction compared to 58 miles by the Kyle Line route.

In terms of cost, this works out as follows: — The Kyle route at 1975 prices is estimated at £3.74 million. The Kinloch Hourn is given as £2.80. Cheapest of all would be another alternative from Ceanncroc Power Station following down Glen Shiel to Glenelg and crossing to Skye north of the village.

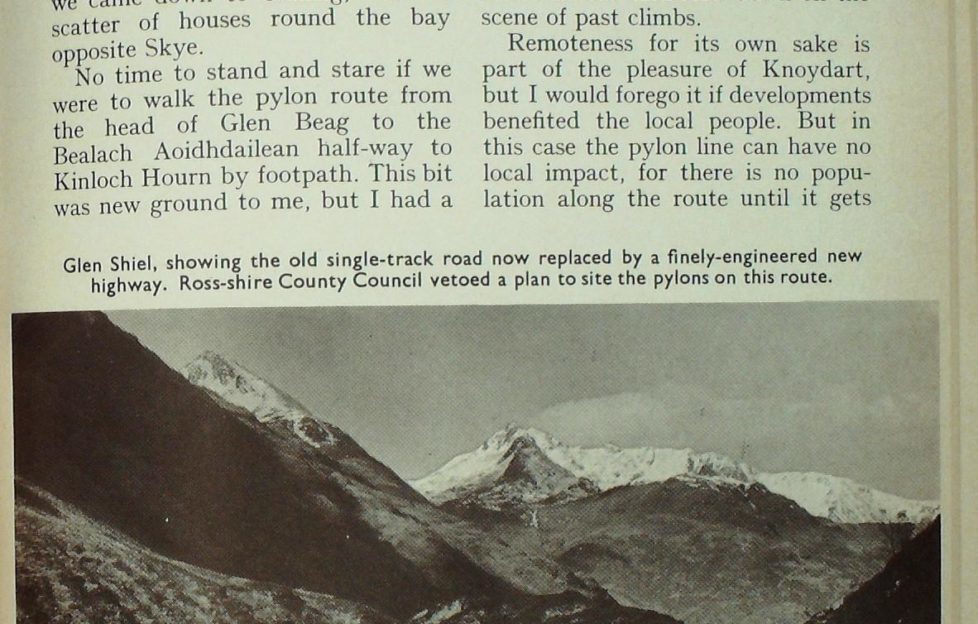

If cost was the only consideration then we should be going for the Glen Shiel route. But this was opposed by Ross and Cromarty on the grounds of amenity, while Inverness did not object to the Kinloch Hourn route.

Luckily the public inquiry to discuss objections to the pylon line will not take account of these county objections, since the land mass from Loch Linnhe to John O’ Groats is now one “Highland Area” covering 2-5ths of Scotland. The inquiry is being held in Broadford from June 17, and it is to be hoped that careful and full consideration will be given to all pylon routes. I say this because fears are being expressed that the Grudie Bridge to Kyle alternative is being soft pedalled.

This must not be allowed to happen, since the total environment is a more important consideration than the small extra cost of the Kyle Line route, which in the end could be cheaper because of easy maintenance. There is also the question of future civil engineering developments in the Loch Carron area making demands on electricity, which would be easy to tap with the minimum of installation artefacts.

…no morning could have been more perfect for viewing it, with new powder snow on the high tops and heat in the sun.

It was dusk before we got back to Glenelg, in the rain, and we were glad of a snug bed and breakfast house, one of a row of Forestry Commission timber houses. By a stroke of luck, too, I met a helicopter pilot who expects to fly in the pylon sections. He had seen the route and condemned the choice of Kinloch Hourn as being crazy from the point of view of maintenance.

Like me, he favoured the line of the existing supply route from Grudie Bridge, but the Board are not in favour of a second transmission line by this route in case both lines should be knocked out of action simultaneously by storm. This seems strange reasoning to me when this route is only half the 1400 ft. altitude of the Kinloch Hourn crossing.

It is good news that the case for generating electricity in Skye is also to be discussed at the inquiry, and I would hope to hear the views of independent consultants on this point before ruling out the possibility. I have the feeling, however, it will have to be a pylon line, for technical reasons of efficiency.

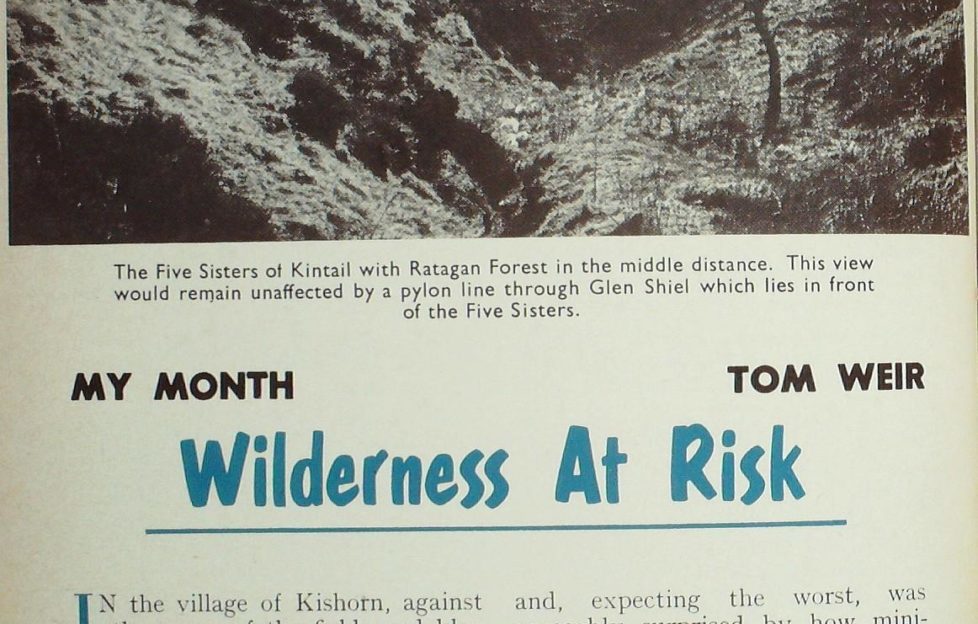

So I reckoned it was time for me to have a look at the Glen Shiel route, and no morning could have been more perfect for viewing it, with new powder snow on the high tops and heat in the sun. Scenically, the finest view in Kintail would be unaffected by the pylon line, namely the panorama from the top of the Mam Ratagan looking over the forest to the peaks of the Five Sisters.

In many crossings of this famous pass I have never seen it look so enchanting as that morning, with the forest gleaming softly on its craggy spurs against the silver of the peaks. The peaks could have been 10,000 feet and not mere Munros.

This is what the Board say about the critical section of Glen Shiel :

There are at present no overhead lines at all and the Glen is regarded by the many thousands of people who traverse it each year as the gateway to the Western Highlands and of immense scenic value.

There is no way in which the Board could carry the transmission lines overhead through the narrower parts of the Glen without it intruding on the view.

But you cannot have pylons without intruding somewhere. If the question is, “Where is the intrusion least harmful?” then there is an unanswerable case for Strath Bran and the Kyle crossing, where future developments are most likely to occur and a pylon line would be of most benefit to the existing population.

After the wintry Highlands it made a fine contrast to go down the Clyde Valley to Hazelbank to visit my friend Torrance Little, of Byrewood. I took a walk with him over his twelve acres of high, sloping orchards overlooking the pleasant reach of the Clyde in this bit of country that could almost be stolen from Kent.

Torrance was well pleased with the way things had come on in the past few days.

“Even in a day you could see the grass get greener, yet a week ago everything was so dreich, wi’ a wind that fair took the nose aff ye it wis sae cauld. The strange part o’ it wis that until March everything was sae far furrit, the buds were almost ready to burst on the plum trees.

“Then in the cauld weather over Easter everything stood still and the buds didnae open until we had these last few warm days. So you could say that things are aboot normal wi’ the peak o’ the plum blossom aroon April 25. Folk usually ca’ it the blossom week-end. What we don’t want now is frost afore the fruit has set.”

The valley was certainly full of promise then, with the first froth on the plum trees, and the early raspberry leaves a fresh green as we took our stroll to see Torrance’s latest fruit-tree graftings, his rows of primulas and polyanthus, cabbage plants, gooseberries, red currants and all the other things he squeezes into the intensively productive ground which he cultivates entirely by himself.

“You couldnae afford to pay a man’s wages now,” he said ruefully.

“I’ve nae tomatoes this year, the cost o’ fuel is too high, and quite a few of the big growers have cut down this year because the market’s sae uncertain with foreign imports. There’s nothing like a Clyde tomato if you’ve the money tae pay for it, but the foreign yins are cheaper to produce. We depend on folks frae the toons coming to the door to buy the soft fruit, but maist o’ the stoned fruit goes to the jam factories.”

Torrance has been a full-time fruit farmer for 19 years. Before that he was a smallholder with a few sheep and cattle beasts, working part-time on a fruit farm until he took over this place. We talked about the economics of fruit farming over the years, and he opined that the growth of week-end motoring had given an enormous fillip to the valley, especially since Glasgow is only 45 minutes distant on the motorway.

We were agreed that to be your own boss was one of the greatest things in life, even if it carried with it a lot of insecurity and taxation penalties.

“Take this farm,” said Torrance. “It’s a cauld spot. We’re north-facing, and high up. Our fruit is always later than doon the valley, but although I say it mysel’, I think I have the best view of anybody. You get fed up at times, but you never get fed up with the view on a fine day when the sun shines and you can look away doon the river to Motherwell.”

The M74 has certainly taken the pain out of motoring. One hour and twenty minutes from leaving Torrance I was home on Loch Lomondside, and at dusk sitting by the loch shore watching bats by the dozen hawking insects over the still water, while gulls by the thousand clamoured over the islands where they roost. Fine to walk home to the drumming of snipe, the crying of peewits, and see the dim shapes of “roding” woodcock night-flighting over my head.

For more of Tom’s columns check back here every Friday.

More From Tom’s Archives…

- June 1975: Wilderness At Risk