Tom Weir | Back To The Hostels

In June, 1976, Tom Weir, a lover of bothys and wild camping, had a change of heart about Youth Hostels. After their warm welcome on a few wild and dreich nights in the hills he has nothing but praise for the handy hostels…

I HAVE to admit I’ve never been a man for youth hostels. I always preferred camping or bothying, for you could be on your own, or with a companion, making your own decisions and getting a more personal sort of adventure in the wilds. Indeed, my first ever stay at a youth hostel was involuntary – and it was a life-saver. Soaked, and carrying heavy bags, we had been on Ben Nevis and Aonach Beag. Then we struggled along the foot of the Mamores eastward, heading for Loch Treig, short of food and finding the burns difficult to cross in their roaring state.

There were two of us, and when we spied a house called Luibeilt with smoke routing out of its chimneys we decided to try to ford the river to reach it. It was a frightening crossing on submerged steppingstones, but we were offered a barn, and when we said we were short of food, eggs and flour were brought out.

It was a remark of the friendly shepherd which decided us to go on.

“There’s a house down at Loch Ossian that was opened only last week for hikers. You would be very comfortable. I would go there if was as wet as you.”

It was a night of bliss

It was a weary pair who confronted the locked door of Loch Ossian Youth Hostel that night. We entered by a window, noted with satisfaction a big stack of dry wood by the fireplace, and in quick time we had a blaze going and our clothes on the pulley while we wrapped ourselves in blankets, made pancakes and switched our eggs to spin them out as French toast. It was a night of bliss.

My next hostel experience was two years later in Glen Brittle when a mighty thunderstorm washed us out in the early hours of the morning. In the grey of dawn we foregathered with other bedraggled campers on the floor of the old schoolhouse, getting a shareout of blankets from the gents’ and ladies’ dormitories. We joined the SYHA to get a roof over our heads on that occasion, and used hostels in emergency in succeeding years of the 30s.

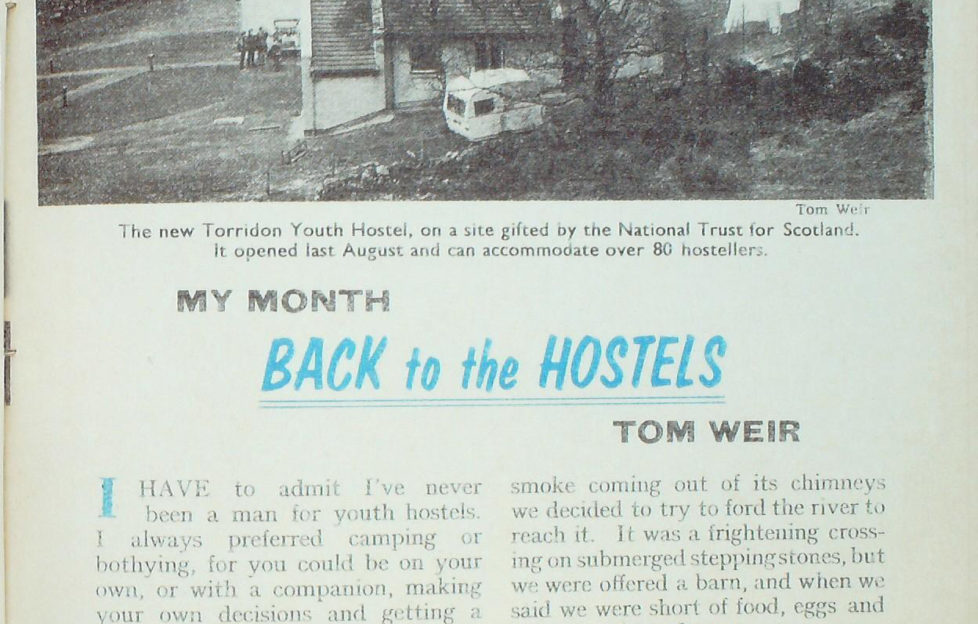

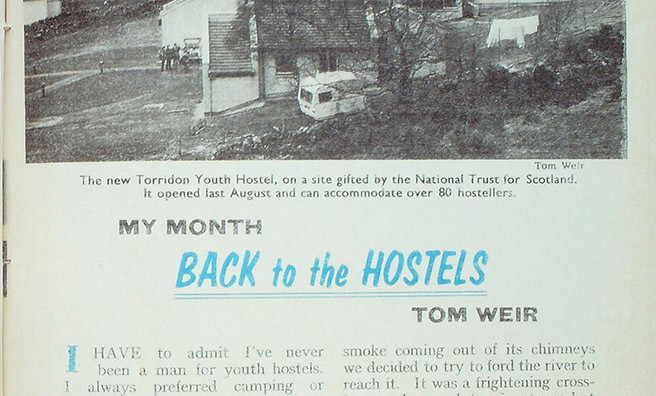

Why am I writing about them now? Because I have just been staying in the poshest youth hostel in Scotland at the head of Loch Torridon. And again, it was unpremeditated. We saw it, went inside out of curiosity to have a look, and were seduced into staying not by its centrally-heated comforts, lounge chairs and comfortable beds. but by the cheery husband-and-wife partnership who run it.

Neil Rieley and his wife Irene arc both of my own vintage. About the time we were being washed out in Glen Brittle, they were tandeming out of Wishaw every week-end heading for the wilds and one hostel or another.

“I was a grocer in the Co-op, so the bike was an escape to the wilds. We were never at home on a Sunday, and in the summer holidays we toured Yorkshire, the Lake District, the Highlands. We hung up the tandem after a tour in Ireland in 1939.”

Designers of the hostel were the firm of Moira and Moira of Inverness, with climber and skier Calum Anton as architect, and I was impressed both by its external appearance — like a little crofting township set into the mountain on five levels — and by the hotel-like layout inside, with spacious lounge and. picture window commanding a view right across Loch Torridon. I liked the large dining-room, and the division of the dormitories, each one holding no more than eight beds, with three rooms for two, so that leaders of school parties can have some privacy.

“I’ve just the room for you,” said Neil, showing us a bedroom better than most modern hotel bedrooms, nothing ornate, but with wash-hand basin, neat furniture and well-sprung mattresses. Nor did we have to take out membership to accept his offer, for we had joined the Association only a week or two before, little knowing how soon we would make use of our cards.

Over tea and home-made scones and pancakes in Neil and Irene’s own snug quarters we talked about the old hostelling days when the big hiking and cycling boom of the 30’s swept Scotland and in quick time the SYHA had bought up croft houses, old schools, castles arid other buildings to create a chain of hostels for cross-country walkers at one shilling a night.

Which put me in mind of Inveralligin where the old Torridon hostel was sited. And as the warden had a sudden rush of business due to the arrival of the afternoon bus from Achnasheen, I took myself off to that charming township four miles along the coast, not for reasons of nostalgia, but to visit an old climbing friend Charlie Rose who gave up a good job in London to live there.

Escaping the city life

Just ten years ago I told the story of Charlie, an advertising buyer in London, aged 37, who sold up everything to come up here with his wife and one child to try and make a new life in the Highlands. It took all the money they had, but they had found the house they were looking for, even if they had to build a road to it, and Charlie set to with the aid of a manual to wire the house for electricity — and it worked!

News had leaked to me from time to time how much they were enjoying the life; that the family had grown to four children, and that Charlie was adapting himself fine to work at anything that came his way. He was in bed when I knocked the door at 5 p.m. and stepped inside a bustling house with toys all over the place and wife busy in the kitchen.

Charlie wasn’t ill. He was about to get up, have a meal and set off for the Kishorn platform site for a stint on the nightshift. It was good to see his bushy black beard again and hear how much he is looking forward to the summer when he’ll get back to boat hiring.

“I’m labouring on the site, cleaning, sweeping. It’s monotonous and boring, but the pay is good—over £100 a week.”

Charlie has always been a keen sailor, and he was soon enthusing about the marvellous days last summer when for two months he was constantly on the go taking visitors sailing round this superb coast so full of good anchorages. I was pleased to hear too that in the winter when Charlie and his wife make toys for sale, success crowns their efforts, and that they could sell more than they can make.

Heartened by all this I left Charlie to get ready for his work and headed back to the Hostel where the kitchen was in full cry, as cooks stirred over the stoves and carried through steaming dishes into the dining room. Great to have a constant supply of boiling water on tap for tea, and in no time we ourselves had fed. Wardening, I noticed, was minimal, Neil just strolling through occasionally, always whistling pipe tunes with the grace notes artfully inserted, and a pause now and then to give a wee bit of advice or help.

“Come on through,” he invited, once the cleaning up had been done and hostellers were settled reading or chatting in the warm lounge. He told me, “It’s been very nice to see the interest the local people have taken in the hostel. We held an open day recently and prepared tea in the hope that a few would come along. About 60 turned up from Diabeg, Alligin, Annat and Fasag. It’s a great community here. We have country dancing in the village in the winter. Your friend Charlie Rose and his wife come to it.”

Seeing them so much at home in such a superb hostel, I reckoned they must have been specially chosen for their vast experience.

“No,” said Irene, ” things have just fallen our way. We’ve always liked the northwest, but when we accepted the temporary hostel at Glen Cottage in December 1973 it took me four days to unpack. I’d made up my mind I wasn’t staying there. The place was in a bad state. The fire was poor, and it was so dark under that big mountain face of Liathach.

“I grew to like it as I got to know the people of Fasag. They were so friendly and helpful. And I got very fond of the hillwalkers who came. I was the warden. Neil was working on this new hostel as a labourer. He did 16 months on it in all weathers. We moved in during the July heatwave cleaning up after the builders and putting in the mattresses and furniture.”

Neil took up the tale. “We enjoyed Glen Cottage, even although there was no privacy. We lived and ate with the hostellers, sharing the same common room and cooking facilities. This is palatial. But it’s the people we enjoy. I’m only sorry we didn’t retire earlier and start the hostel wardening before 1972.”

“Tell me about the building of this hostel,” I said, for I had heard how hard the work was. ”Well they were short of men. No drains had been dug. The walls were only five feet high when I started, and the gales were so bad that winter that they were blown down five times before they finally stood up. Sometimes there were only two of us on the job. The foreman died of a heart attack on the site. The biggest number of workers we ever had was 21, and one week I put in 81 hours for my biggest wage of £55. Other times it could be just over half that.

“It was Irene who started us on this course. Our family, two boys and a girl, had married and left home. I had been self-employed for 25 years, ever since coming out of the army. We had a licensed supermarket in Wishaw turning over £55,000 a year. Bigger supermarkets were coming in and we felt the time was right for selling out.

“I hate to be idle. I’ve always been keen on woodwork, so I began to do a bit of cabinet-making again. I had made bookcases, tables and display cabinets in the past. It was Irene who took on the wardening at Kyle Youth Hostel for a probationary period, while I went back to shop-keeping with a part-time job in the Co-op butchers. We were there from 1972 until 1973, and, do you know, in that second season we had only six nights without a singsong in Kyle. We enjoyed it. I’d get out the Jew’s harp or the mouth organ and set them going. Or even blow up the bagpipes!

“We’ve sold-up in Wishaw now, our house there and everything else. Officially, I’m the warden, but Irene is the other half, though we have a first class local girl as assistant warden. We get one day off a week, or should do, for we haven’t had it yet, there’s been so much to do. We were full up at Easter.”

I asked about discipline.

“People are happy to conform, when they know what’s expected of them. We try to keep the hill-walkers together in the dormitories, for they tend to bed early after hard days on the hills and they want away sharp in the morning. Motoring types tend to talk later. School groups can be very good, it all depends on the leaders. We don’t have any bother.”

In Neil’s philosophy a hostel is more than just a roof over your head, but a place to enjoy for its companionship.

In the sunshine of next morning we took the road to Shieldaig. It’s a road I can never take for granted remembering how hard the local people fought to get it built. This time I had a new tingle of anticipation, for Charlie Rose had told me that he thought I would be able to motor right round the north Applecross coast, since the foundations were completed and only the two miles between Lonbain and Snad remained to be tarred.

In the past, I had motored as far as Kenmore, but not on a scenic day like this one, with the soft green of the Caledonian pines glowing, and the pink bark matching the warm Torridonian sandstone as fore- ground to the sparkling crofts of Shieldaig, Alligin and Diabeg along the blue lochside.

New houses have already been built along the new road and I was glad to see that derelict ground had been cultivated by the settlers. I am told there would be a rush for all the empty crofts if the estate made them available for sale.

After Ardheslaig, tucked into its own wee harbour of Loch Beag, the road climbs dramatically to cross a little moorland with lochans where a pair of sleek divers floated, showing slightly uptilted bills and robin-red throat markings. A snipe was drumming and a golden plover fluting when I lowered the window to glass the elegant birds.

Beyond Kenmore, most thriving of the villages, lies Fearnbeg and Fearnmore, then the road turns abruptly south and runs to Cuaig, where I turned off and knocked at a door hoping for a chat.

The old age pensioner who opened the door soon got over his shyness and began voicing his feelings about the road. He liked it, and the thought of life moving back to the place. He remembered when every one of the 12 houses was occupied and the wee school had 21 scholars. Everybody had a cow and sheep, and the land was in cultivation.

” It could come back to that yet,” he said, meaning that it is our last resource if industry should fail. The present population of Cuaig is nine, three of them children who travel to school in Shieldaig with the others of this lonely coast. On from Cuaig, and I knew that easy driving had come to an end when I saw heavy machinery ahead, and without preamble struck what looked like the bouldery bed of a burn with pools of water stranded in it. Even creeping along I took some bad bumps.

Evidence of the difficulty of blasting this track was everywhere in the amount of rock lying around. I knew where I was, because I had walked this in the past, and a fine moment it was when the track began dipping to the inlet of Sand, and suddenly exchanged the boulders for smooth tarmac, causing me to bless the Royal Navy whose recently acquired base speeded up the building of this road. Sand is the perfect name for the curve of bay where the low Naval station stands. The water beyond it is the deepest anywhere round the coast of Britain. Torpedo-testing markers now dot the coast.

In Applecross village I was relieved to hear that because of the barrier of the Bealach nam Bo, and the fact that there is no licensed hotel, the platform yard on the other side has had little or 110 impact on the village. Fishermen have not given up fishing to work in it. However, they fear there may be some congestion on the fierce zig-zags of the Bealach nam Bo once the road is open later in the summer when motorists begin making the coastal round by Kishorn or Shieldaig, since the twain must meet.

One popular stop on the road is going to need a special lay-by, and that is at the place where it is passible to look down on the big Meccano set of the yard where the biggest platform in the world is being built. Huge as the camp is, with dormitory ship and dozens of squat buildings, the whole thing is dwarfed by the scale of mountains and sea. It should be more impressive when the platform base is floated out to be built offshore to its full height of around 700 feet.

To contrast the most modern Grade One hostel in Scotland with an old-fashioned Grade Two, we chose to spend that night in Kyle, and the young warden went through the motions of turning up his nose when he saw our cards had been stamped in Torridon the night before. ” This is what hostelling is about,” he said, with a wave of his hand to the old schoolroom which is now kitchen and common-room combined.

It was certainly lacking in any refinement; no lounge chairs here, only wooden benches, old tables, a big Aga cooker for general warmth, and two big dormitories, one for men, the other for women, with toilets adjacent. Of the score of inmates there were youngsters from America and Spain. The only one of our own mature vintage was an English parson on a cycling tour heading for Torridon.

Neil Rieley would have called them a very quiet crowd, content to sit round the cooker chatting, though most of them read and went to bed early. In the dormitory there was no noise, and by 9 a.m. every-body had cooked breakfast and hostel chores had been done

As we drove off, I was thinking of chat night, soaked and utterly weary, when we reached Corrour and went in through a window, and of the shilling a night we didn’t pay. Today it costs £1.20 for a night in a Grade One hostel, and £1 for a Grade Two if you are over 21. In a Grade Three hostel the price is 90 pence.

Torridon is away out in luxury over all other hostels because it was built under the Countryside (Scotland) Act, 1967, by Ross and Cromarty County Council on a site gifted by the National Trust for Scotland. Financial aid came from the Countryside Commission for Scotland, the Highlands and Islands Development Board, the late John J. Calder of Braemore, and the Cross Trust.

In return for cash it offers the best value in Scotland, but too many youth hostels like it would change the nature of the folks who seek them out.

The Scottish Youth Hostel Association’s ideal remains —

To help all, but especially young people of limited means living and working in industrial and other areas to know, use, and appreciate the Scottish countryside and places of historic and cultural interest in Scotland, and to promote their health, recreation, and education, particularly by providing simple hostel accommodation for them on their travels.

What ideal could be more worthy than that? Times have changed so vastly since these words were written that the phrase “people of limited means ” has to include motorists, whose custom is now so necessary for the welfare of the movement.

You can read more of Tom’s escapades here, where a new column is published online every Friday.

More from 1975…

More from 1976

More instalments every Friday