Tom Weir | Shepherd of Artney

In June 1977, Tom Weir wrote this column for us on his friend, Pat Macnab, a traditional shepherd.

It is incredible to think of how much has changed in this country since Pat’s youth, but though the roads may reach further and narrow trails wider, his spirit of adventure remains today

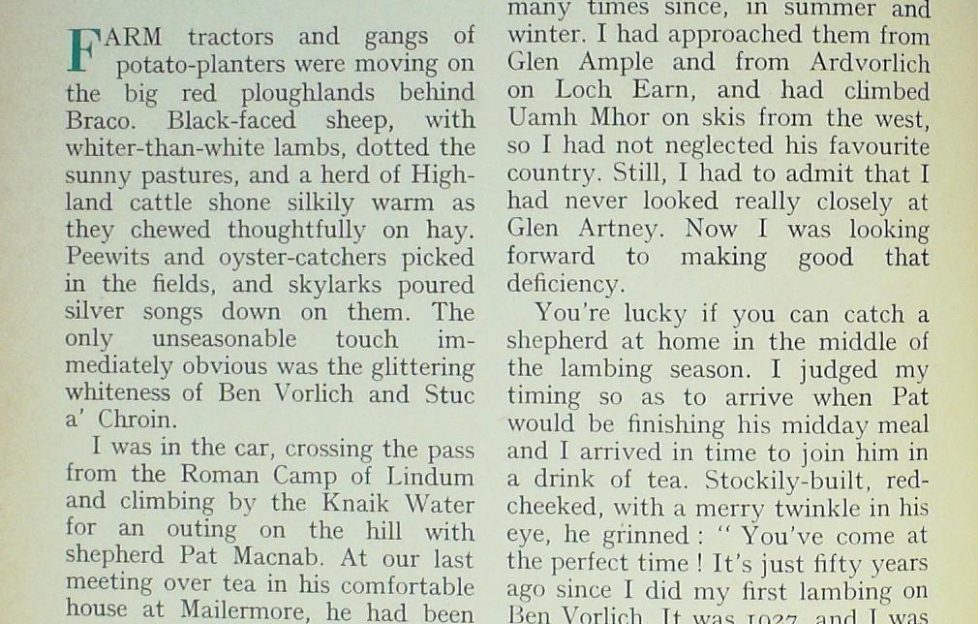

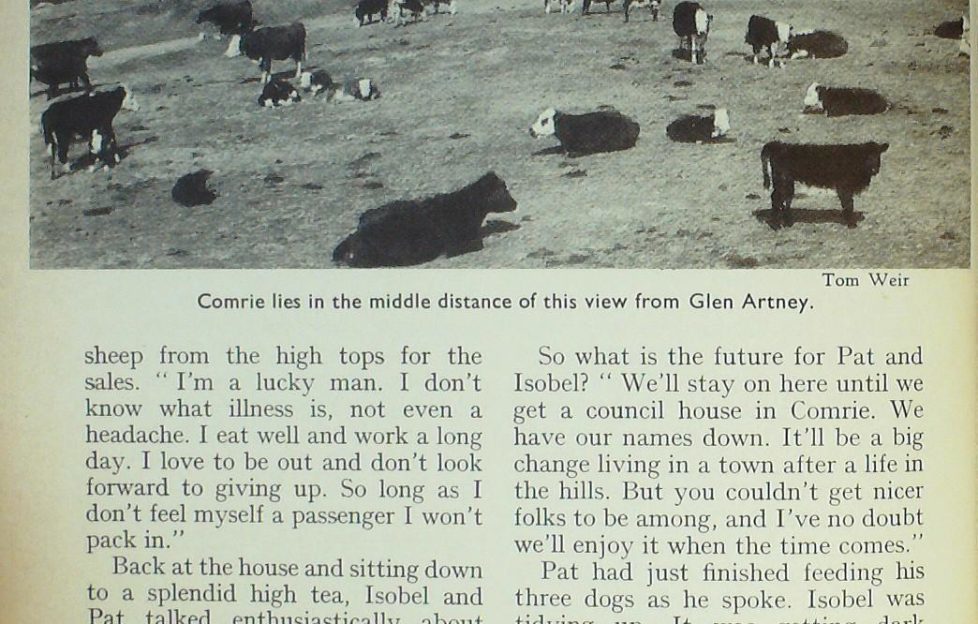

Farm tractors and gangs of potato-planters were moving on the big red ploughlands behind Braco.

Black-faced sheep, with whiter-than-white lambs, dotted the sunny pastures, and a herd of Highland cattle shone silkily warm as they chewed thoughtfully on hay. Peewits and oyster-catchers picked in the fields, and skylarks poured silver songs down on them. The only unseasonable touch immediately obvious was the glittering whiteness of Ben Vorlich and Stuc a’ Chroin.

I was in the car, crossing the pass from the Roman Camp of Lindum and climbing by the Knaik Water for an outing on the hill with shepherd Pat Macnab.

At our last meeting over tea in his comfortable house at Mailermore, he had been regaling me with stories of a happy life shepherding the glen which his father had herded before him.

A long-term Scots Magazine reader, he told me that he had long hoped to open at “My Month” and read about Glen Artney, but so far he had waited in vain.

I was looking forward to making good that deficiency…

To that I told him that I had indeed written about Glen Artney; and I recalled how two of us had arrived by bus at Comrie on a Saturday night to sleep out under the stars for the pleasure of hearing the dawn chorus of the birds on a May morning. And how, before even shepherds were awake, we had lit a wee fire to cook our eggs and chops.

Afterwards we had climbed from the limit of the public road by the path up the Gleann an Dubh Choi rein and by the south ridge of Ben Vorlich to circle over Stuc a’ Chroin, returning by the Keltie Water to Callander and the bus home to Glasgow.

True, that trip was a long time ago, but I had been over these peaks many times since, in summer and winter. I had approached them from Glen Ample and from Ardvorlich on Loch Earn, and had climbed Uamh Mhor on skis from the west, so I had not neglected his favourite country.

Still, I had to admit that I had never looked really closely at Glen Artney. Now I was looking forward to making good that deficiency.

You’re lucky if you can catch a shepherd at home in the middle of the lambing season. I judged my timing so as to arrive when Pat would be finishing his midday meal and I arrived in time to join him in a drink of tea.

Stockily-built, red-cheeked, with a merry twinkle in his eye, he grinned.

“You’ve come at the perfect time! It’s just fifty years ago since I did my first lambing on Ben Vorlich. It was 1927, and I was 14. I stayed in the old house of Dubh Choirein —you’ve slept in it so you know it’s not much of a place, but it was furnished in those days. It was a hard beginning for a lad, but I had been well trained under my father.

“It’s the lower ground we’ll be on this afternoon. I want to see the gimmers are right—the young sheep that are having lambs for the first time. It’s been a long, hard winter for them, what with snow and floods.”

Caring for the flock

With the dog in the back of the car, off we went to the parks that drop steeply to the rocky ravine where the Ruchill Water foams over the Spout of Dalness. Pat had been over the ground in the early morning. Dog at heel, he moved quietly back and fore across the slopes, eyes everywhere to see that none of the new-born lambs had been deserted.

Then, satisfied, he swept his hand towards the river, and told me he would take me to see his bridge, known locally as Pat’s Brig, since the one shown on the map was swept away.

The descent to the bridge on a path through gnarled birches was pure charm, past the ruins of a former crofting township, with, above it on the south-facing slope, green rigs of old cultivation encircled by a huge oval of grassy field-dyke enclosing many acres.

“That’s all been reseeded and treated with chemicals to get rid of the bracken and make grazing.”

Below us was the rocky gorge, and slung across it a wooden bridge supported on twin trunks as long as telegraph poles.

“It was some job hauling up the poles and balancing them over to the other side. We had to choose the very highest rocks because of the spates here. The Ruchill rises tremendously fast because of all the burns flowing into it. You see that huge boulder in the dry bit of the river-bed? It was shifted several feet from the bank in the last big flood.”

We turned down-river now, past the rusted stanchions of the demolished bridge to the spurting white cataract of the Spout of Dalness, the only waterfall on the Ruchill.

To let the salmon up, a rough fish pass has been hewn in the rocks at the side, making it into a sanctuary area where no fishing is permitted. Comrie Angling Club have the rent of the entire river.

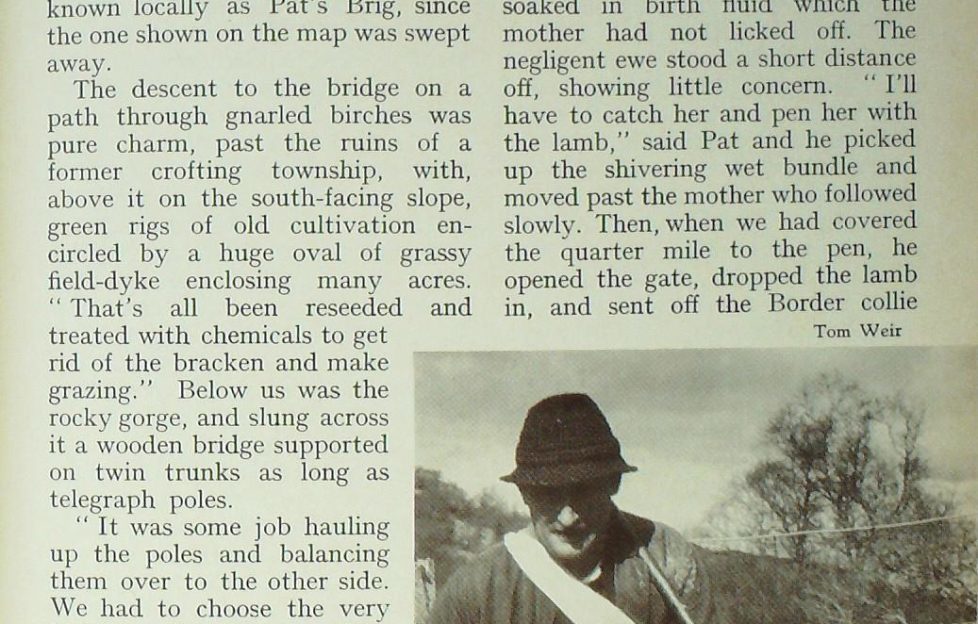

Back amongst the gimmers we came immediately upon a lamb soaked in birth fluid which the mother had not licked off. The negligent ewe stood a short distance off, showing little concern.

“I’ll have to catch her and pen her with the lamb,” said Pat and he picked up the shivering wet bundle and moved past the mother who followed slowly.

Then, when we had covered the quarter mile to the pen, he opened the gate, dropped the lamb in, and sent off the Border collie who neatly separated the gimmer from its neighbours to be grabbed by Pat who turned her over to squeeze the udder to test for milk.

Very little squirted out and he shook his head with concern.

“Any lamb can live for 24 hours on what is already inside her at birth. I’ll have to come back to this one later.”

We talked about the effect of weather on the ewes.

Of times gone by…

“Today is fine. But on the hill four days ago, you couldn’t hold up your head for drift. It was a winter blizzard! The problem is the big number of sheep. In my father’s time — and he shepherded until he was 78 — a hirsel was 400. Mine is over 800, and I have to do it on my own. I can’t handle a number like that and lamb them the careful way he taught me, though I do my best. We have five shepherds for a summer stock of 900 sheep. It goes down to half that number in winter.

“But things are easier for me in some ways than they were for him. We have good medicines and sheep dips. Maggots and disease was a curse in my father’s time. In his day, you had to do a lot of doctoring. Of course, we’re better paid than ever he was. Wages are high now, changed days from the £27 10s. the half-year I got in Morven in the 1930’s.

“I liked Morven very much. They were all Gaelic speakers. I know a bit myself for I was born on the Island of Eigg and both my father and mother spoke it.

“The place was at Kinloch Farm on Loch Teacuis and during the three years I was there, I never got back to Glen Artney once. The St Kildans came to Morven when I was there, to work in the forestry and they had never seen a tree in their lives some of them.

“The young ones settled but the old folk soon wanted back to their island.”

Climbing up the hill to Mailerfuar, formerly a gamekeeper’s cottage but now a hay barn, we commanded a fine view up and down the glen, from the earthquake centre of Comrie following the swell of the sandstone and conglomerate hills to their apogee on Uamh Mhor at 2181 feet, beyond which are the harder rocks of the Highland Boundary Fault.

There was a severe tremor in 1839, with rumblings like thunder. People in Comrie were terrified and the kirk opened for prayer.

When we dropped down to the school Pat became reflective, remembering that there were 27 on the register in his day, and now it is closed.

“It’s the only school I ever went to. From April to October we never wore shoes. I didn’t notice the two-mile walk to school, for my feet were like leather. In the holidays I was never away from the horses. The estate kept 150 ponies, which they rented out to other shooting lodges at £1 a week. I was horse-daft and helped break them, take them to the smiddy, and go with them to the grouse moors at beating time. Although my father always had a low wage, we wanted for nothing in the way of food. We had grouse, venison, rabbits, everything that was going.

“My mother kept open house, and nobody went without. For entertainment, there were plenty of fiddlers and accordionists. There was a barn for dancing.”

I asked about the population.

“When the shooting lodges were staffed in summer, it could rise to 150. It never gets above two dozen now. I did every kind of job in the glen, from ghillie to killing rabbits, then in 1938 one of the shooting tenants, a Mr Latilla, offered me a job on his estate at Balcombe, in Sussex. I was to be a gamekeeper, because I knew about grouse and deer, but the main job was rearing pheasants. I got on great. It was there I met my wife, who was a parlour-maid in the big house.”

“Upstairs – Downstairs!”

Back at the house, I had a chat with Isobel, who hails from Egremont, in the Lake District, and has a lively sense of humour.

“Upstairs- Downstairs!” she laughed. “And I was back to being a maid after I married Pat in 1940, when I went to work at Drummond Castle, near Crieff, when Pat went off to the R.A.F.”

Drummond Castle is the seat of the Earl of Ancaster, who owns Glen Artney.

Pat’s R.A.F. career lasted six years. Demobbed at last, he came back to shepherd Glen Artney from a cottage called Dalclathick, one mile off the beaten track, without running water or toilet until he made one. Isobel described that convenience.

“It was unusual. It had a square seat, because Pat is no joiner, and didn’t know how to make an oval one! I used to carry the clothes down to the burn to wash them. I think these years at Dalclathick were some of the happiest. We did get a modern house, but Pat was restless, and wanted to move.”

The move to Lanarkshire was in 1953.

” The year of the Coronation,” said Pat. “The bonfire on Tinto was still burning when we got to the house where we were to live, at Parkhall. I knew they had different ways of handling sheep on those hills, and I wanted to learn them. We were away 17 years, and I worked in three different places, finishing up on the Lang Whang. But Glen Artney was always in our minds, and we came back six years ago.”

The glen, of course, is very empty compared to what it used to be like.

“We’ll go up and look at the head of the glen, and you’ll see Dalclathick, the old cottage without water, which we still think of as home.”

There it stood in the sun, which it gets from four in the morning until sunset, Pat told me.

“We had a wee Norwegian cart and a pony when we lived there, and when our daughter took pneumonia, it was on the cart we took her to Comrie. Now, you would ring for an ambulance. For entertainment, you turn on the television. These things don’t make up for the folk who have gone, who rallied round to help you. Folk are very mobile now. My mother made only one trip a year from the glen, and that was to the Rural outing.”

Just across from the old cottage, and linked to it by footpath, stood the Auchinner, the house where Pat had been brought up.

“My grandfather died in it, and my uncle left Glen Artney only eight years before my father came to it, so the Macnabs have a long connection with the top of the glen. I’ve herded every hirsel from top to bottom. My daughter was the first lassie to be married in the wee kirk for 50 years.”

I asked him about retirement, knowing that many shepherds over 60 look forward to an easier life, without long hours of walking from dawn to dusk through six weeks of lambing, then the work of marking, clipping, dipping and gathering the sheep from the high tops for the sales.

“I’m a lucky man. I don’t know what illness is, not even a headache. I eat well and work a long day. I love to be out and don’t look forward to giving up. So long as I don’t feel myself a passenger I won’t pack in.”

Back at the house and sitting down to a splendid high tea, Isobel and Pat talked enthusiastically about their special delight, fiddle music of the Scott Skinner kind.

“You know, I heard him play in Comrie. I’ve never forgotten it. I’ve never envied any gift in any another man except the ability to make music, especially singing. That’s something I would love to have been able to do.”

We looked at family photos. Their two boys and two girls are married now. Three of the four live in England, the fourth is in the Royal Navy at Rosyth. The shepherding link is broken.

So what is the future for Pat and Isobel? ” We’ll stay on here until we get a council house in Comrie. We have our names down. It’ll be a big change living in a town after a life in the hills. But you couldn’t get nicer folks to be among, and I’ve 110 doubt we’ll enjoy it when the time comes.”

Pat had just finished feeding his three dogs as he spoke. Isobel was tidying up. It was getting dark outside, and time for me to be out of their road for they would have to be up in the morning before daylight while I was lying in bed.

A seasoned campaigner

Back home, I had a shock when I opened the newspaper and read of the death of an old clubmate, Ben Humble, frequent contributor to this magazine. He died on April 16, at Grantown-on-Spey on the same day that a letter from him appeared in the Press headed “How To Cut Down Mountain Accidents.”

In honour of that seasoned campaigner, I quote the words he wrote just before the stroke that killed him. His general theme was that too many climbers carry ice-axes with no idea of how to use them. He cited three recent deaths:

“Complete records for 1976 show that almost all winter accidents to hill walkers in snow involved ice-axes. This was also the case, though to a much lesser extent amongst climbers.

The Mountain Rescue Committee of Scotland repeat the rule laid down by the American Alpine Club that all who seek out the mountains in winter, and most particularly beginners, should have at the beginning of each winter season one or more days’ training under skilled instruction on proper use of ice-axe on safe lower slopes before going high.

Were this followed out in Scotland, there would be a much lower accident and fatality rate on our hills.”

That particular quote could almost be Ben Humble’s epitaph, for no man in the history of mountaineering has been more devoted to the cause of safety.

Over the 40 years or so I had known him, he had recorded and analysed deaths and injuries on the Scottish hills. A tenacious man, his aim was to have a Mountain Rescue Committee of Scotland. We have it, and everyone was delighted when Ben was awarded the M.B.E. for his services.

Ben was 73 when he died. Small, bespectacled, round-faced and completely bald, he had gusto and a Puckish sense of humour, sometimes expressed in wild, cackling laughter, infectious to everyone within earshot.

When I knew him first, he was a dentist, noted for his work in X-ray photography applied to the mouth, but owing to increasing deafness, he gave it up, and turned to writing and photography as a livelihood.

Out and about on the hills, youth hostelling, sleeping out in caves, he wrote of his adventures and edited a magazine called The Open Air In Scotland. He made no pretence of being a great climber, but was more than a hill-walker, as his books, On Scottish Hills and The Cuillin Of Skye show. His photograph of the Cioch, with Bill Murray on it, perched above the clouds, is one of the best pictures ever taken on Scottish hills.

His favourite mountain was The Cobbler, and for a time he lived in Arrochar in order to write and be near it. But the lure of Glenmore Lodge, and the fun he was finding leading parties of youngsters over the Cairngorms, drew him to build a house in Aviemore.

It gave him a new lease of life, for he loved company, and got it amongst the instructors and children. Any friend was welcome to stay in his house, provided they had sleeping-bag and food, for Ben was a bachelor, who could not be expected to look after them.

In his time, Ben must have introduced hundreds of schoolchildren to the Cairngorms, walking with them, camping and enthusing them with the joy of the tops. He loved athletics and record-breaking, and was very proud of the fact that two years ago he had climbed Ben Macdhui from the Lairig Ghru in exactly the same time as it had taken him 20 years before. In his early youth, he laid the foundation for his stamina by cross-country running and cycling.

To my mind, however, his greatest accomplishment was how he overcame his handicap of deafness. He faced the silent world and overcame it by sheer force of character. He was a doing man, who got things done. If you go to Glenmore Lodge, look at the Alpine and heather garden he built, and think of him.

We’ll have another column from Tom Weir’s archives next Friday.

More from Tom…

Two years’ worth of Tom’s columns for our magazine are now available online.

Click here to find another great read to find out how much (and at the same time how little) has changed in 50 years.