Tom Weir | In All Kinds Of Weather

The spring of 1976 wasn’t the best for weather, but from Braemar to Banchory, and from Bearsden to Bridge of Cally, there was no snow, ice or rain that could stop Tom Weir getting out and enjoying the countryside

TODAY, January 24, is crisp and brilliant, black ice on the road, the Highland hills sparkling white, the loch grey-blue and the shores attractively green behind the rich colours of the islands crowned with glistening oaks and Scots pines. The wind is from the north, but the sun feels warm after one of the worst weeks of gales that anyone can remember, driving before it rain, hail and snow.

With west-facing windows like ours, living in the house has been like camping on an Atlantic island, with trombone blasts playing tunes through slits in the door. Newspapers tell us how lucky we are, with their stories of ships in trouble all round the coast, ferry services off, London trains running up to 10 hours late, cars being blown off the road or colliding on ice or smashing into fallen trees. Chimneys have crashed down from high rooftops, and while snowploughs were out on the A9, other ploughs were being used to clear seaweed and sand from the Oban esplanade.

The hard fact in Scotland is that you never know what you are going to get when you leave home for another part of the country, I had this rubbed home once again when I met up with Adam Watson in Braemar for a ski-ing trip. Roads in the West were clear, but in Braemar the snow lay several inches deep and the overhead conditions were so vile we opted for the shelter of the woods by taking the track up Glen Quoich.

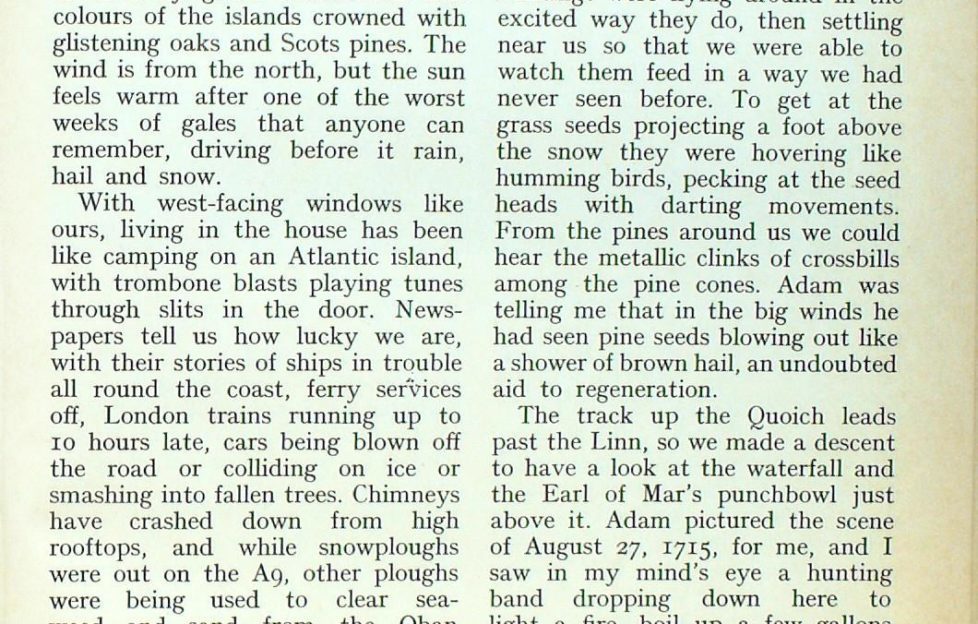

Yet lying above the trees in the deep heather were hundreds of deer, chewing the cud, getting more shelter than if they stood up. Snow-buntings were flying around in the excited way they do, then settling near us so that we were able to watch them feed in a way we had never seen before. To get at the grass seeds projecting a foot above the snow they were hovering like humming birds, pecking at the seed heads with darting movements. From the pines around us we could hear the metallic clinks of crossbills among the pine cones. Adam was telling me that in the big winds he had seen pine seeds blowing out like a shower of brown hail, an undoubted aid to regeneration.

The track up the Quoich leads past the Linn, so we made a descent to have a look at the waterfall and the Earl of Mar’s punchbowl just above it. Adam pictured the scene of August 27, 1715, for me, and I saw in my mind’s eye a hunting band dropping down here to light a fire, boil up a few gallons of water in a huge pot, then carry it over to a big pot-hole in the rocks.

Now for the ceremony of pouring whisky into the pot, adding honey to it, then pouring in the boiling water. The Jacobite punch was ready for drinking. And little doubt the nobles and chiefs who made up that company toasted “The Rising”—which was to end in disaster at Sheriffmuir.

Adam quoted to me John Grant’s description from the book, Legends of the Braes 0′ Mar :

“So the hole was, and is still named, the Earl of Mar’s Punch-bowl, and a proper good utensil it was, and capacious withal.”

Unfortunately, the big pothole must have had a thin bottom, for it is punctured now, and has been since last century. Glen Quoich is derived from Cuach, meaning Cup Valley, so maybe Mar when he made the punch in the pot thought it was time it lived up to its name. It is still a remote glen, and its Caledonian pines and birches are among the best in the Cairngorms. It was dusk when we came back down the path, hardly disturbing the red deer stags feeding. They merely raised their antlers and stared, then got back to pawing the snow to uncover the heather.

Adam lives in Banchory, but drove back next day to meet me despite even worse weather of steady snowfall. It was another day for the low ground, so, donning our skis, we set off for the golf course and spent some time on the wee hill above the clubhouse before setting off round the junipers of Morrone, our heads down to the swirling flakes. There was not much to see other than blackcock, a few fieldfares and the odd capercaillie. The most interesting sights were when we swung down to the Dee, and at its junction with the Quoich saw that its whole surface was made up of moving fragments of brash, formed by snowflakes landing on the water and forming up with others into icy pancakes. Because of the low temperatures the snow- flakes were not melting but consolidating.

While we watched the sliding mass accelerate over the rapids we saw one of the floating pieces had a bird on it, a dipper, stealing a ride, then plumping into the water to reappear farther up and hop on to another piece. It kept doing it, and no doubt between stances it was walking on the bed of the fast- flowing Dee searching for food. In the white world the brown band across its chest looked almost robin-red. A hardy bird, the dipper. Seton Gordon has a record of one at the Wells of Dee, at 4000 feet on Braeriach — a British record.

The snow had changed to rain when Adam left that evening. But within an hour it was freezing again, and by morning the scene was like Siberia with blowing snow. Our intention was to meet again for a climb, but I wasn’t surprised when Adam phoned suggesting I join him at Banchory for a local walk since the Cairnwell was blocked.

Talk about weather changes! Ten miles of difficult snow driving suddenly ended at Ballater. At Dinnet the sun was shining and the snow tinsel glittering on the trees. In Banchory there was no snow and the fields were green.

“We’re always lucky here,” grinned Adam. “We get the best weather on Dee-side, even better than Aberdeen!”

We drove off up the Feugh to the Forest of Birse for a sunny afternoon in a natural pine wood which began regenerating during the last war. After the snows of Deeside, this was a colourful world of russet bracken, bottle-green pine needles and silver birches. Little did I know when I left Adam to drive over the Slug Road to Stonehaven that I was to be driving in snow and mist most of the way back to Gartocharn.

* * * *

It was fine to meet up again with the man I wrote about last month, Dr Ian MacPhail. With him I was now to visit what had been the most north-westerly frontier of the Roman Empire when it stretched all the way from Turkey to Old Kilpatrick. Ian, a Dumbarton man, is at present writing a history of Dumbarton Rock, and when I picked him up at his house he guided me down to the old Forth and Clyde Canal bridge below Old Kilpatrick.

“This is where Antonine’s Wall ended,” he explained. “The terminal fort stretched from where we are standing right up to the houses of Gavinburn Hill. It had to be big, for it held 2500 soldiers, 500 of them cavalry. The A82 runs along the northern rampart of the fort. All sorts of finds have been made here, Roman and pre-Roman, coins which date the Wall, bits of pottery, and, not so long ago, a Roman altar. You can see them in the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow. Now we’ll go to Cleddans—it’s just above the dual carriageway.”

In five minutes we were scrambling up to a farm perched on the Kilpatricks.

“The Wall always keeps to the high ground. It had a ditch on its north side 40 feet deep and 12 feet wide in a V shape. Cleddans means ‘The Place of the Ditch’ —and there it is, or what remains of it after 1800 years.

” The Wall itself must have been 20 feet or more below us. It went east from here to Duntocher, crossing Golden Hill over there. From where the Wall ended at Old Kilpatrick a ford led across the Clyde to a network of roads on the other side, with protective forts at Bishopton and Inchinnan. With the building of the Erskine Bridge, this Clyde crossing has become important again—history repeats itself. Now we’ll drive over to Golden Hill and follow the Wall to Bearsden.”

As Ian was explaining to me how the hill got its name from the gold coins found on it, we noticed a middle-aged man wearing earphones sweeping the turf with a metal detector. Next minute he signalled to us that he had made a find. He marked the spot then he made a neat cut with his knife and removed a little piece of turf. He extracted a coin covered with earth. Alas, it turned out to be only a threepenny piece a few years old.

“I’ve never found anything worth yet,” he said philosophically. “It’s only a bit of fun. But my son’s found a few things.”

Some of the ditch is visible at Golden Hill, and a bit of the stone base of the Wall lies exposed. On this 14-ft-wide base the Wall itself was built of turf, tapering 10 feet tall, but wide enough at the top to allow two patrolling soldiers to pass. Ever)’ two miles there was a fort. Golden Hill had one. Castle Hill, just beyond us, had one. Another has been discovered recently at Bearsden.

It was to Bearsden we went next, to visit the site of the Fort discovered in 1973 with its bath house and finds which include pottery, ironwork tools, glass and the head of the Goddess Fortuna. Appropriately, this fort, which experts thought had been lost for ever, was found just off Roman Road.

Then we walked through New Kilpatrick Cemetery to look at another bit of Wall foundation, perched high and commanding the ground below the Campsies where the Wall stretched east for 37 miles across the narrow neck of Scotland between the Forth and the Clyde. The best bits of the Wall, at Rough Castle and Castle Cary, are in the care of the Department of the Environment, and we shall be going there another day.

Our ancestors, the Picts, were undoubtedly a thorn in the flesh to the Romans, who had to build Hadrian’s Wall from the Solway to the Tyne to try to keep them out. But for 43 years the Romans had some 10,000 soldiers garrisoned along Antonine’s Wall. Then they dismantled the Wall, threw the altars and distance slabs into wells and ditches, and took their departure. All but one of the distance slabs have been recovered, which, I think, is remarkable.

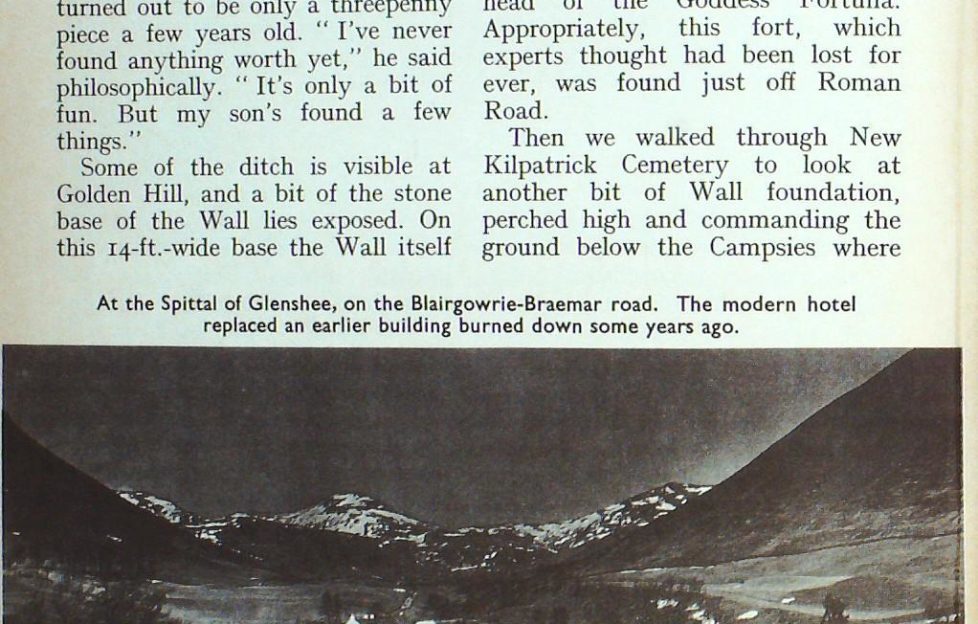

Glen Shee was in the heart of Pictland, and it was there I went next to meet my friend lain who lives there. A foggy drive most of the way, then a delightful surprise— sunshine at Bridge of Cally, with the fleeces of sheep shining white on the green knolls below the high farms and brown moors. Ahead, black storm clouds buried the Cairn well, where I thought we would be going.

“I don’t think so,” said Iain. ” What about that Kirkmichael to Lair right-of-way you’ve talked about? Why don’t we use the two cars and do the cross-country walk?” So off we went.

First stop was Kirkmichael to drop one car there, and drive back to Glen Shee in the other. The only snag was that the black clouds up the Cairnwell had moved down to us, with a marvellous side-effect— rainbows as the showers hit us, but the sun still shone from behind. Iain hates stops for photography, but it was he who shouted, “Camera!” as I tried to capture an absolute blaze of a rainbow burning on a black sky.

“I can even see the pot of gold!” He pointed to the splash of colour where the bow hit the shining green-sward. With the whole bow visible, and sometimes double bows, it was a glorious drive to Lair where we parked the car under a uniformly grey sky.

Guns cracked from the hillside above as we donned our boots and we could see the shooters up on the skyline as we climbed. No need to wonder what they were shooting at for the heather was moving with white mountain hares. They sat so tight we nearly trod on some of them.

The shooters posed a problem for us; leave the path and find another way across the hill, or go ahead and maybe spoil their sport. We opted for leaving the path and taking the Allt Coire Lairige, rough but interesting walking over a wee pass to drop into Coire a’ Bhaile. The latter word indicates a township, and no doubt this former settlement was the reason for the Kirkmichael-Lair path. It is said that the folk who lived here emigrated in a body to Australia or New Zealand.

Now we struck the real path, which climbs past a reedy lochan where mallard duck rose in a flock and a family of whooper swans gave out “clang-clong” calls of alarm before taking to the air and circling the water gracefully. One mile on and we came to the outbuildings of Ashintully Castle, where sorting out one track from another is none too easy because of the farm.

Four years ago the Scottish Rights-of-Way Society tried to sort out the problem by preparing markers for signposting the path. However, the local laird refused to co-operate, claiming that the right-of-way had lapsed through not being used. The society took the matter up with the old Perth County Council but could get no satisfaction. I entered the fray in The Scots Magazine, appealing for users of the Kirkmichael-Lair path to write to me, and I obtained enough detailed documentary evidence to show that this path had never fallen out of use. This was passed to the Scottish Rights-of-Way Society, who got in touch with the new Tayside Regional Council. They have now passed it to the District Council. A letter has recently been received from them acknowledging that there have been several complaints from walkers about this path.

My advice to walkers is: keep using it. Don’t allow yourself to be bluffed, nor let the District Council off with not doing their duty to the public. The real importance of the Kirkmichael to Lair path is that it is part of a network of paths stretching from Pitlochry right across the hills by Kirkmichael to Glen Shee, to Glen Esk, a distance of a hundred miles, crossing the glens of Isla, Prosen and Clova on the way. That long-distance walkway would be well worth marking, and would be infinitely more valuable than the Lairig Ghru and Glen Tilt —Countryside Commission please take note.

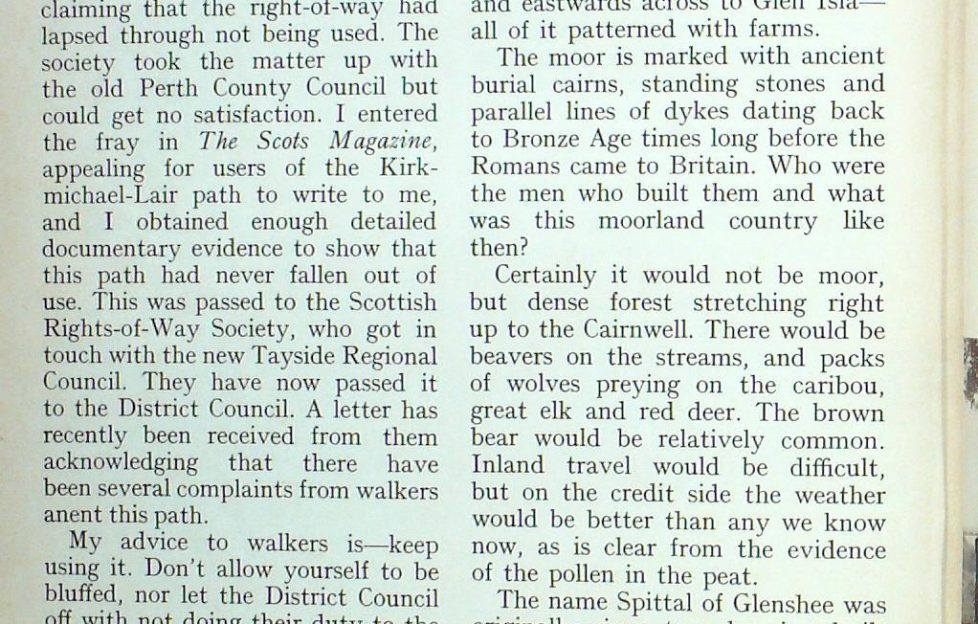

Next morning was none too promising, so we went out on an archaeological ramble from Bridge of Cally. Our route was south above the bridge, through birch woods alive with siskins and redpolls, then through Forestry Commission spruces to come out on Cochrage Muir for good views of the Sidlaws and eastwards across to Glen Isla— all of it patterned with farms.

The moor is marked with ancient burial cairns, standing stones and parallel lines of dykes dating back to Bronze Age times long before the Romans came to Britain. Who were the men who built them and what was this moorland country like then?

Certainly it would not be moor, but dense forest stretching right up to the Cairnwell. There would be beavers on the streams, and packs of wolves preying on the caribou, great elk and reel deer. The brown bear would be relatively common. Inland travel would be difficult, but on the credit side the weather would be better than any we know now, as is clear from the evidence of the pollen in the peat.

The name Spittal of Glenshee was originally given to a hospice, built in the 16th century as a refuge to travellers who might be caught out at night when wolves were still a menace in the Highlands.

It is no wonder the Scots are a hardy race. They have had to be to survive. As Neil Munro put it in one of his poems:

“God’s pity on you folk and your weather.”

You can read more of Tom’s escapades here, and a new column is published online every Friday.

More from 1975

More from 1976

- March 1976: In All Kinds Of Weather

More instalments every Friday