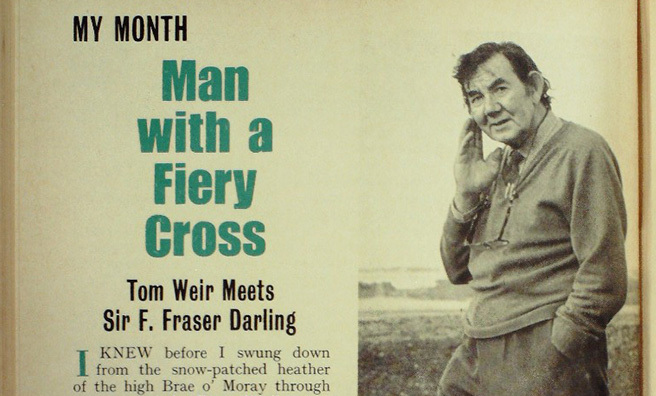

Tom Weir | Man With A Fiery Cross

In May 1975, Tom Weir’s monthly column for

The Scots Magazine described his interview with

the great world ecologist, Sir F. Fraser Darling . . .

I knew before I swung down from the snow-patched heather of the high Brae o’ Moray through the pines of the River Findhorn to Forres, that on this visit I was going to range far beyond the Moray Firth, for I was on my way to meet a man who had laid the foundation of his fame living and working in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. None other than Sir Frank Fraser Darling, who, after his global travels as a world ecologist, has retired to live at Lochyhill on the outskirts of the town.

To be invited to spend a day with him talking about the past and the present was indeed a very great honour, for we had met only once before, at a lunch party, and hadn’t exchanged a word, for he had lost his voice and couldn’t even manage a whisper. That was before he left Scotland and went to America, where he never failed to acknowledge his debt to the Scottish Highlands which had taught him to see and think about the landscape in a way that no one had done before.

I know that the book which most profoundly affected my own outlook was his Natural History in the Highlands and Islands. It came out in 1947, and today is rightly regarded as a classic.

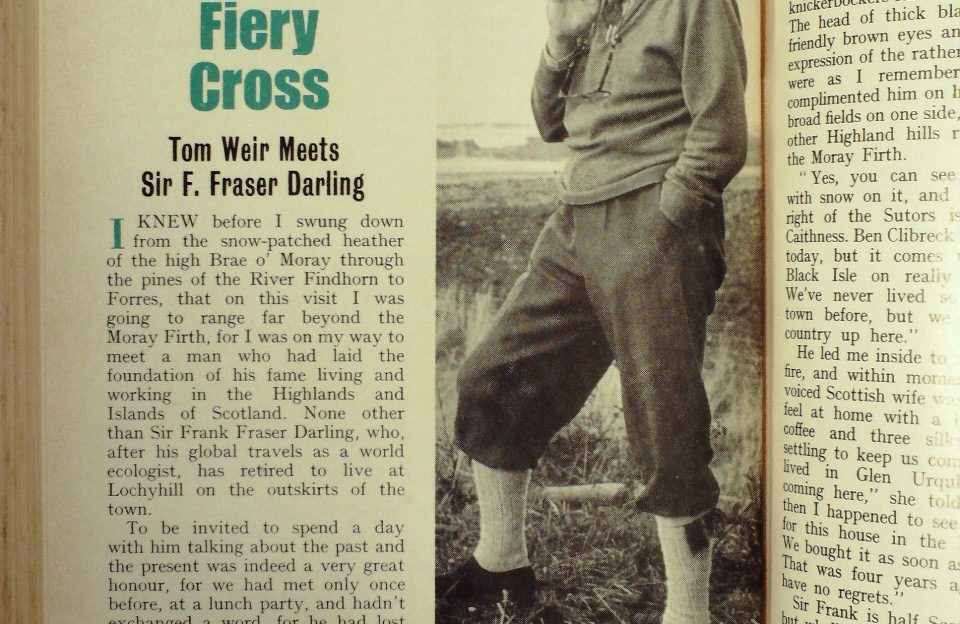

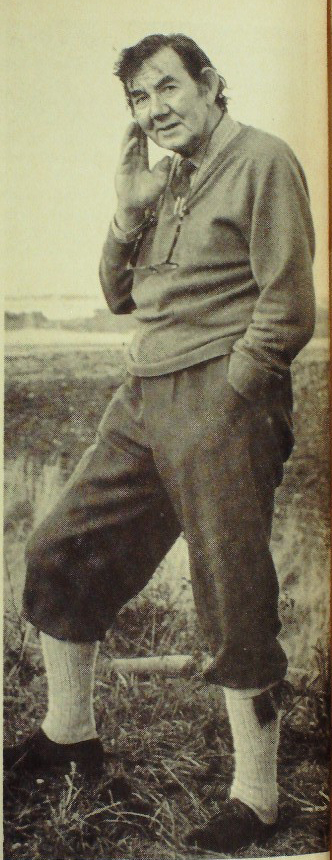

So you can imagine I was fairly excited as I drove through the farm steadings to a hilltop house fringed by pine trees. And as I got out of the car a tall figure in jersey and knickerbockers came out to meet me.

The head of thick black hair, the friendly brown eyes and the kindly expression of the rather sombre face were as I remembered them. I complimented him on his view, over broad fields on one side, while on the other Highland hills ranged above the Moray Firth.

“Yes, you can see Ben Wyvis with snow on it, and away to the right of the Sutors is Morven in Caithness. Ben Clibreck isn’t showing today, but it comes up over the Black Isle on really clear days. We’ve never lived so close to a town before, but we feel in the country up here.”

He led me inside to a blazing log fire, and within moments his soft-voiced Scottish wife was making me feel at home with a large cup of coffee and three silky Pekingese settling to keep us company.

“We lived in Glen Urquhart before coming here,” she told me, “and then I happened to see the advert. for this house in the local paper. We bought it as soon as we saw it. That was four years ago, and we have no regrets.”

Sir Frank is half Scots by birth. but wholly Scots by instinct.

“It’s inevitable that a cross-bred from Northern England will choose one side of the Border or the other. I knew I would come back finally to settle in Scotland, but not to the West Coast. It’s too wet. And it’s too touristy nowadays. At 71 I have no career ahead, and this old farm-house is a good place to be. I don’t want to travel unless I can walk, and I’m not fit for that now.”

Looking around me at the elegant Chippendale furniture, the beautiful bird paintings on the walls and the fine, hand-carved objects on his bookcase, I could not help thinking of Eilean a’ Chleirich out west from Loch Broom, and the hut which was his first island home.

. . . a tiny house with presses and shelves for everything, set down in your

own fairy country beyond the reach of the external world. I had played and

pretended this bit of escapism all my life and here it was, as good as the

pretending, and perhaps a. little better, for I had with me those I loved.

“As a philosophy of life, I doubt whether my pleasure at that time would

hold water, but as a moment in a lifetime it was perfect, reaching its apogee

when a flock of barnacle geese came low in front of the window and landed

a hundred yards away at the foot of the burn.

He had written that in Island Years.

“You know,” he smiled, “even when a hut was all I wanted, and lonely places were all that mattered, there was a side of me which still wanted beautiful works of man, highly civilised things, works of art.

“But there is a time for everything. That was all part of my first experience of putting the work I wanted to do before money. My dream was an island. But I began with the life history of the red deer. As a naturalist, I wee happiest working in a field never touched before. Nobody had studied the life histories of Highland animals and bird flocks and the breeding cycle. My wife – I was married to my first one then – was really splendid. She accepted my giving up my job in animal genetics in Edinburgh, and she came up to Loch Broom to live with me on a Leverhulme Fellowship of £350 a year. And even that sum was guaranteed only for two years.”

It was from Brae House, Dundonnel, that Fraser Darling launched himself on An Teallach and the big wilderness to the south of the Strath na Sheallag. And it was here that my own beginnings overlapped with his, for we had a mutual friend in Calum MacRae, the keeper at Carn More, who lived in what was possibly the remotest house in Scotland. Calum used to tell me about the lug fellow from Dundonnel who lived like a deer so that he could watch what the beasts were doing night and day.

I had envied him greatly then, not only for the full life he was leading in these favourite hills of mine, but for his skill as a writer. I told him as we sat at the tire, how his books had affected me as a teenager. It was the kind of life-style I wanted for myself.

“Writing was the only thing I was ever good at,” he chuckled. “I had a good tutor who pruned me down. I knew l could make money from writing, enough to keep a wife and child and live the kind of life I had chosen. It was the writing that paid for the work. And I’ve been a very lucky man, for until I was 67 I never knew anything but youth. I never knew what it was to be middle-aged. Then, four years ago, I had a stroke. Suddenly I slowed up, and I’ve been an old man ever since.”

I asked him which of all his island experiences he cherished most. The reply came without hesitation: “North Rona.”

“I felt completely fulfilled on Rona. The immensity of the ocean was so absorbing in itself.”

He went on: “I felt completely fulfilled on Rona. The immensity of the ocean was so absorbing in itself. The seabird cliffs in spring and summer, one of the most thrilling things a man can have to watch. I remember how, on August 10, they were gone, and at the end of the mouth the seals were hauling ashore and building up to thousands. It was seeing so many deaths among the pups through overcrowding that I realised there could be too many Atlantic seals on one breeding island, and that there could be a way of managing them for their own good.”

Here is a little vignette on Rona from Fraser Darling’s pen:

Enormous waves broke against the cliffs and the water was Churned

to white foam for seventy-five yards from their foot. It was the sort of

sea of which people sometimes say ‘Nothing could live in this terrible surf.’

So you would think, but close in to the rocks and where the waves broke

most fiercely were our friends the great seals. They were not battling

against the sea but taking advantage of them for play . . . They were

keeping to the surface, nearly a hundred of them, enjoying the deep

rise and fall of the sea and the spray of shattered waves.

They were living joyfully, and I in my own way rejoiced with them.

The sky was a shining vault of blue, the sea was a. deeper blue, and as

we watched the surf grew even bigger. The whiteness of it shone in the

sunlight, and the movement and sound of it all were glorious. In those

days I think we were lifted out of our earth-bound humanity for a space.

I have a good idea of what that sea was like, for on a May day at the Clo Mor cliffs, Cape Wrath, I have seen the waves breaking white over distant North Rona. Listen to his description of a December gale:

When I went for water I had to crawl over the ridge on hands and knees.

Fianuis was impassable for a short time. The sunrise that morning had

been a magnificent show of blood-red and cerise, which always bodes ill.

After the tantrums of the afternoon we had thunder and lightning at night;

the thunder came in single claps, just like great explosions and were rather

frightening, because for the first two or three I saw no lightning and could

hardly believe they were

thunder, the sound being mixed with the great

noise of the wind.

Yet in our conversation Fraser Darling did not dwell on the mental strain that these winds imposed, especially at night when the door of the hut bent and the roof lifted.

For as the hut creaked and the crockery rattled, they were uneasily conscious of how narrow was the neck of land called the Fianuis on which they were perched. Only 40 yards separated them from the nearest of the bursting waves, and only two yards westward was the mighty Atlantic swell.

After the storms came rare days of calm. One was especially memorable. They awoke, three clays before Christmas, to a frozen Rona, white after snow squalls.

Never had we seen the view so magnificent as on this which was to be our

last morning. The sun was behind the far clear line of the Sutherland hills

and tinted the whole of our snowy world a rosy pink. The atmosphere was

clear and still, and even as we watched I spied a dot thirty miles away

between Cape Wrath and the Butt of Lewis. A ship undoubtedly, the first we

had seen for a month, and it must be the cruiser coming for us.

We may never see Rona again as we saw it that morning early. No one else alive has been there at such a. time, but we felt in these quiet moments by the chapel that our farewell was not for ever.

Sir Frank took up the story:

“We went back for the summer birds, but not to study the seals for a second breeding season. We were living on Tanera of the Summer Isles by that time, and I was going to make that the base for my seal studies. My intention was to purchase a 40 ft. ‘Fifie’ so as to be able to visit different seal nurseries, for I held that the separate stocks of Atlantic seals remain discreet.”

The year was 1939. “We were at war, and I couldn’t even go into the army, for back home on Tanera on my way to milk a cow I had a slip on the wet grass, my leg went crack, and I knew it was broken. I had enough sense to know that whatever I did I shouldn’t try and walk the 300 yards home, that somehow I would have to crawl up the wet grass of the hill on two hands and one knee. No hope of calling a doctor with the south-wester that was blowing. My wife set the leg from instructions in a St John’s Ambulance book, and in six weeks’ time when the doctor saw it he said it couldn’t have been done better if l had fallen on the steps of a hospital.

“Lame for a year and out of the war, l decided we should stay on at Tanera, farm it as effectively as possible and be sell-sufficient so as not to be a drain on the country. We were losing convoys at sea and I felt it dreadfully. By working the best land on Tanera intensively, and making the soil more productive so as to carry more stock, I could pass on the message via my writing. We farmed, and I wrote articles in the Highland papers, and published a little book about crofting agriculture.

“People tell me I have a lasting monument on Tanera—the hill still shines green after all these years.”

“The Highlanders listened to what I was saying, because I wrote as a practising crofter, and as one who had been brought up on farming. Moreover, I liked the work. People tell me I have a lasting monument on Tanera—the hill still shines green after all these years. We changed it from heather by carrying up shell sand. Animals grazing on it have kept it good ever since. But there; is little interest in crofting as a way of life today.”

Island Farm tells the story of bringing life back to Tanera, and how the conviction was forced upon husband and wife that one family is too small a unit to live alone on a small island. The boy, Alasdair, was at Gordonstoun School then, and came home only at holiday times. He is now a doctor of medicine, and lives in the Midlands of England.

“When we left Tamera,” said Fraser Darling reflectively, “l had to re-educate myself about division of labour. I had been used to trying to be at both ends of a baulk of timber. The move to Strontian on Loch Sunart, where we had a gardener, a cook, a housemaid and a team of people working together on the West Highland Survey, restored the balance.”

The book which resulted, West Highland Survey – an essay in human ecology—is the work I consider to be the most valuable single reference book ever written about the Western Highlands and its people. But Fraser Darling shook his head

“I was very green when I put up the idea for that survey. I had been asked to nominate my own salary as director, and because of the war and the fact that I was making £2000 a year out of writing, I put myself down for £600 a year. I felt I could not take any more money, considering the position we were in as a nation. But the effect of my action was that I depressed the survey in status.

“Also, the Department of Agriculture for Scotland loathed my guts because I had stolen a march on them. After years of work the Report was finished and six copies sent to them. They never even acknowledged their receipt, though I heard they were being well thumbed. Nor would they allow the Report to be published for another three years.”

West Highland Survey is preoccupied by the human condition, which can be made better in every respect. Natural History in the Highlands and Islands describes the whole ecological range of our marvellous country, and it preaches the need for a “Wild Life Service” devoted to studying unique areas in order to conserve them and their wild life for posterity.

The Government took action by setting up the Nature Conservancy in I949 for this purpose, but the man most fitted to be its Scottish Director from the standpoint of scientific attainment and experience in the field was not invited to take the post.

Sir Frank chuckled merrily as I aired that view.

“I never applied for it! Later I became a lecturer in Edinburgh University, and spent a great deal of time travelling. But I did feel squashed by attitudes within the Nature Conservancy. I wondered if everybody else was right and I was wrong about what was happening to the natural world. In America, when I went there in 1949, it was different. I lectured and met men who were as concerned as I was about population and pollution and the disappearing wilderness.

“I came back knowing I was right, and that great opportunities were being lost. In the early 1940’s you could buy some of the finest scenic land in Scotland for 7s 6d and 10s an acre. And that would have been the time to purchase it for the nation and set up National Parks. I was a member of the Ramsay Committee in 1943, defining the five areas. I was also on the big committee which produced the good second report, but no action was taken. Now we can’t afford to buy the land, but wilderness should have some legislative control. I hear that an Arab sheik has just bought a big sporting property in the North West. I hope he will do better than the Arabs have with the onyx.”

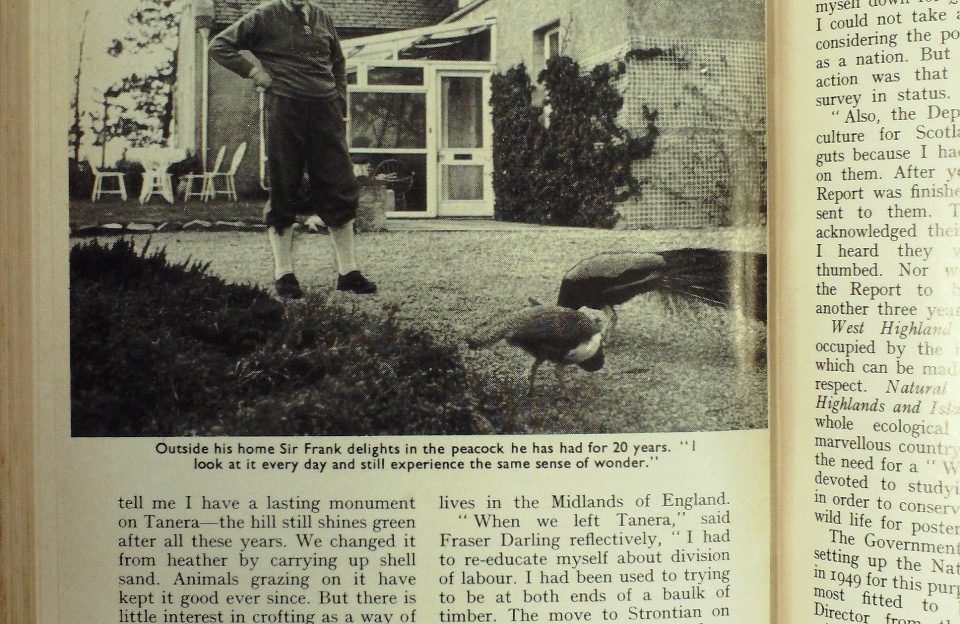

Breaking for the family lunch, I saw another side of Sir Frank Fraser Darling as he talked about his passion for building dry stane walls and the delight of having a glorious peacock strutting on his lawn.

“I’ve had it for 20 years. and I wouldn’t like to be without it. It’s a bird such splendour. I look every day, and still experience the same sense of wonder.”

“Even for a pessimist, it is still a beautiful and wonderful world. Are we going to destroy it completely?”

After lunch he showed me some of his treasures; a leopard cub in a curled position sculptured from Portsoy marble by Margaret Findlay. (“I knew l had to have it whenever I saw it”) On the same staircase was a realistic snowy owl in Danish Porcelain. He handed me a little short hammer, its smooth shaft beautifully fitting the hand; its adze was of slate held on by thongs. The next thing I held was a bronze dagger, green with age. Above these works of early man was a glowing Russell Flint painting of Spanish dancers with castanets and whirling skirts.

“See that rug beneath your feet. Notice the tassels hanging from the end of it. What do you think these were for?”

I soon saw when he picked the rug of intricate Afghan design off the floor and opened it out to show it was in the form of a sack.

“Yes, a camel bag, a pannier. Can’t you just imagine the camel being unloaded at the end of the day, the goathair tent being set up and the rug tied inside as at draught-excluder and hold-all?”

Many of the things in the house are mementos of travel.

“Yes, it was the Americans who gave me the chance to spread my wings. Working for them was my longest time in single employment, thirteen years, and with all the opportunities to carry out one’s ideas. I could even endure New York. The Conservation Foundation, of which I was vice-president, is financed mostly by rich men with open minds: no catch-penny terms.”

In the U.S. he became a panoramic ecologist, looking at the world in totality, seeing what man was doing to it in America, Africa, Asia or wherever, advising, writing, helping to set up National Parks, sitting on United States committees as well as committees in Britain.

“And it was because I was known in America that I was. picked to give the Reith Lectures for the B.B.C. Thirty years of work on Government committees meant little, but what the U.S. gave to me in friendship and opportunity were the punch in my Reith Lectures, given my original convictions.

“I have never had very much ambition, except to live the life I wanted. I have no career ahead, and plenty of time now to think – one of the compensations of age. Perhaps I will still write something. There are so many threads. I suppose you could call me an antidevelopment man, and to be that is to be a misfit in this modern age.”

Sir Frank Fraser Darling has done much more for Scotland than make a brilliant success of his own complex field of study, which is man in relation to his environment. The fiery cross he lit on the Summer Isles and North Rona has never gone out. It was Fraser Darling who inspired a student by the name of John Morton Boyd to become a biologist, and he is now the Director of the Nature Conservancy Council, Scotland.

Moreover, it was Dr Morton Boyd who carried on the seal work on North Rona, begun by Sir Frank Fraser Darling. I remember Morton telling me in Glasgow University that if he could achieve even a tenth of what Fraser Darling had done he would consider his life well-spent. And while Fraser Darling was in Africa studying conservation problems, Morton was appointed Regional Officer for Western Scotland, with St Kilda and North Rona as part of the study area.

And the two names came together again when the time came for a revision of Natural history of the Highlands and Islands, though the title has been changed now to The Highlands and Islands, so we see the fulfilment of the original dream. The vision remains, and other fresh minds will go to the high hills and the lonely islands and find an ecstasy that cannot be put into words.

As I left, Fraser Darling said, “Even for a pessimist, it is still a beautiful and wonderful world. Are we going to destroy it completely?”

For more of Tom’s columns check back here every Friday.

More From 1975…

- May 1975: Man With A Fiery Cross

More from 1976…

- May 1975: Man With A Fiery Cross