Tom Weir | Secrets of the Muir

The 60-70 tonne Auld Wives Lift stones were ones Tom Weir had passed many times, but he had never thought to look closer until a professor from the University of Glasgow showed him the ancient carved faces…

OFTEN enough in this magazine I have written about my old Knoydart friend John MacDougall who used to shepherd the big hills of Glencoe, until the loss of “the third part of his breath ” obliged him to seek out a gentle wee hirsel on Craigmaddie Muir between Milngavie and Blanefield.

Since he was almost my neighbour, I went for a stroll with him often enough on his 6oo-ft.-high heathery ground, delighting in his enthusiasm for sheep and listening to his humorous turn of phrase as he recalled events of early days that seemed to belong to another world. I remember saying to him on his 83rd birthday, “John, you must be the oldest working shepherd.” There was a long pause as he sucked his pipe. Then came a typically droll reply, “I think I am the oldest in the world.” Another pause, then the punch line, “I feel it, anyway !”

John was a lonely man when his employer sold the sheep. I think he was happy to go, when, almost 90, he died last year, the last of my friends of an irreplaceable old school. He was in my mind as I motored past the road-end of the wee cottage where he finished his life, and instead of driving home I turned off to use the last hour of daylight for a walk on the moor and listen to the curlews.

I made my way over to the pile of three stones called the Auld Wives’ Lifts, scrambled to the top, and sat there feeling very reflective. John had never liked this moor, nor these strange stones which have a legend attached to them. The folktale is that three witches wagered each other as to who could Carry the heaviest stone in their aprons. Two put down their stones side by side. The third one capped their efforts by placing on top of the other two stones a great flat one. A variation of the same tale is that it was a trial of strength to see who could throw the farthest stone, and the biggest stone landed on top of the other two.

Hugh Mac Donald in his classic Rambles Around Glasgow (1854) gives a good summary of the conflicting beliefs held in the 19th century about the origin of the stones:

“By some this gigantic cromlech is supposed to be a Druidical altar, whereon, in a dim, prehistoric era, the dark rites of pagan worship may have been celebrated.”

On an old map it was shown as a “Druidical Cromlech,” and the cavity between the stones was thought to be for the reception of the human remains after blood sacrifice.

I took all that lot as auld wives’ tales, and accepted Geikie’s verdict that the Lifts were a glacial erratic; blocks of stone carried down by the ice and dumped as the glacier died. That evening I looked at the stones more closely than I had done before, remembering what a perceptive friend of mine, Peter G. Currie, felt about them. Currie wrote down his thoughts about the Lifts in this magazine in the March issue of 1974 :

One looks suspiciously at grass around the stones, green island among dark heath. After all those centuries, does this ground still record what happened? No matter, it needs little imagination to convince one that the place still smells of blood.

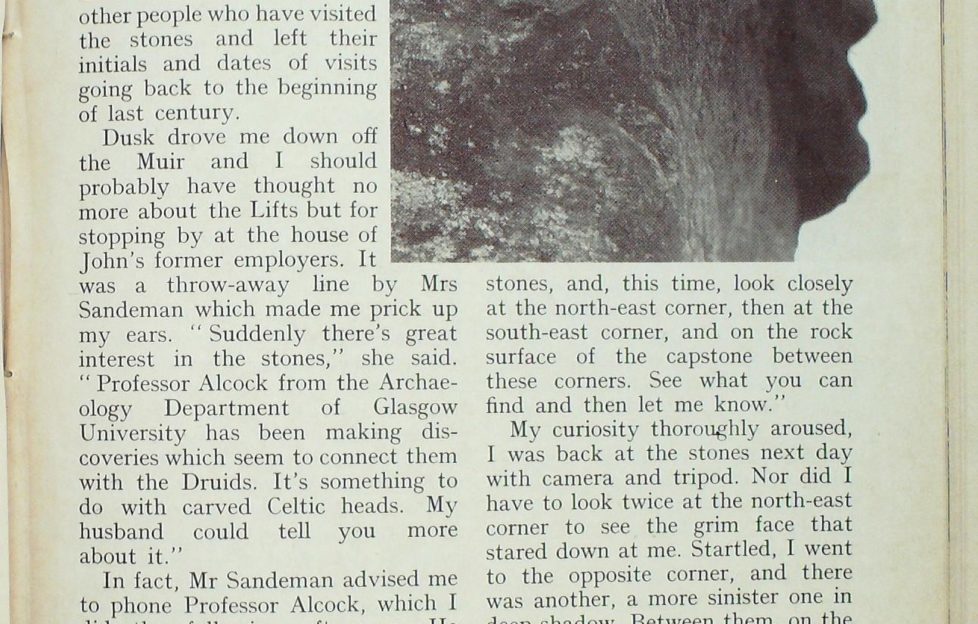

Currie described his feelings of terror when, as a youth, he scrambled alone on the stones. And he told how he had a feeling of evil and unease when he went back again as a mature man. No such inhibitions seem to have affected the numerous other people who have visited the stones and left their initials and dates of visits going back to the beginning of last century.

Dusk drove me down off the Muir and I should probably have thought no more about the Lifts but for stopping by at the house of John’s former employers. It was a throw-away line by Mrs Sandeman which made me prick up my ears.

“Suddenly there’s great interest in the stones,” she said. “Professor Alcock from the Archaeology Department of Glasgow University has been making discoveries which seem to connect them with the Druids. It’s something to do with carved Celtic heads. My husband could tell you more about it.”

In fact, Mr Sandeman advised me to phone Professor Alcock, which I did the following afternoon. He told me he was a regular reader of “My Month” and a keen climber.

“So you’ve known the Lifts for a very long time,” he said. “Tell me what you’ve noticed when you’ve been there.” I had to confess that it amounted to very little, except a crop of initials and dates chiselled into the sandstone.

“Now that’s very interesting to me,” he said, ” and you’ll realise why when I tell you my tale. But first, I want you to go back to the stones, and, this time, look closely at the north-east corner, then at the south-east corner, and on the rock surface of the capstone between these corners. See what you can find and then let me know.”

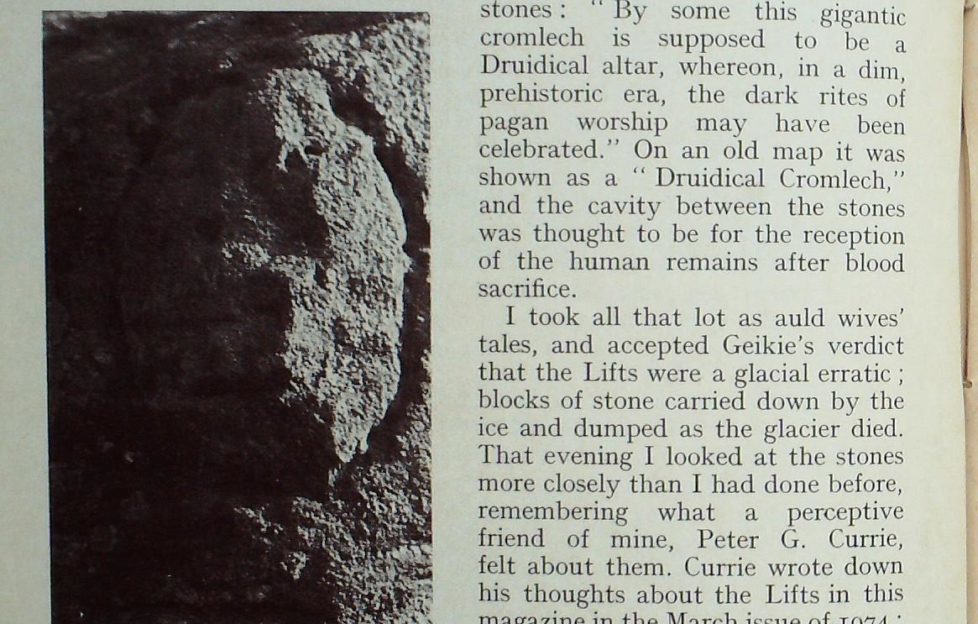

the grim face stared down at me from the stone

My curiosity thoroughly aroused, I was back at the stones next day with camera and tripod. Nor did I have to look twice at the north-east corner to see the grim face that stared down at me. Startled, I went to the opposite corner, and there was another, a more sinister one in deep shadow. Between them, on the flat surface, were two other heads, and another two round the corner. These last two were at the very place where I had climbed up the previous day, yet I had failed to notice them.

I phoned Professor Alcock next day and told how amazed I was. He then wrote to me:

“Your reaction of amazement that you’d not seen them before is a common one. I have myself taken a party of students, some of them acute observers, to the Lifts, and have been amused to see them fail to recognise the faces even after they had been repeatedly told they were missing important features on the rocks.”

On the phone again, he told me, “I think it’s not beyond the bounds of possibility that the capstone was placed on the top of the two smaller stones by the Celtic people who carved these heads. The vertical Lift is not a big one, and it could have been done with wooden rollers.”

I asked him who the people might have been who could have erected and worshipped at this Druid shrine. “I think we could call them Celtic people under Roman influence. The carvings recall the severed heads of Gaul — one of the leading images of Celtic religion. Notice, too, that the heads are confined to the east and north, while the two most arresting of them look out from the north-eastern and south-eastern edges. That would be a remarkable coincidence if the heads were the work of casual visitors.”

What I wanted now was an independent view as to the probable origin and arrangement of the stones. Dr Ingham and Dr Rolf of the Geological Department of Glasgow University were in no doubt they were of glacial origin, but beyond that were not prepared to go. Professor Alcock writes:

“That one of the few (stones) should happen to have been deposited on a pair of supporters may be a remarkable coincidence; that it should have been set virtually level, its irregular undersides fitting the irregularities of the supporters, and its long axis matching the gap between them may be stretching the coincidence to inacceptable lengths.”

we were in the midst of archaeological treasure

So a strong case would seem to be building up that the heads have been there for a very long time, yet they do not appear to have been studied until 1975. Now we turn to initials and dates carved on the stones. The dates go back to 1807 and give us an idea how weathering affects the colour and sharpness of cuts on the rocks. The heads have an ancient mellowness as if darkened by time. In support of this evidence there has turned up an old photograph dating to the 1880’s and showing three of the heads.

As for the weathering of the sand-stone there is yet another source of comparison, for, on the rocks just east of the Lifts, there are cup and ring markings dating back 4000 years, and they are still wonderfully distinct. These markings are of the Bronze Age period, 2000 years before the Iron Age Celts.

Nor is this all that has been found on this remarkable moor, for just east of the Lifts, Professor Alcock has been excavating two chambered tombs, and near them are burial cairns, while among the rocks there is a little millstone quarry with stones in every state of manufacture, from roughly pecked cuts to the finished article, complete with hole in the centre.

Little did I know when I used to walk here with old John that we were in the midst of archaeological treasure, with mysteries all around us waiting to be solved, mysteries like the heads which we failed to see, symbols, perhaps, of decapitation and blood sacrifice on a moor which may have been sacred, since no trace of human habitation has been found on it.

After all this introspection, I drove off to the Borders with my wife as guests of the Hill Walking Club at their Annual Dinner — their very first for the club has only been going for a year. Nor was it to be a town affair, but to follow a day on the hills of Yarrow to give us an appetite.

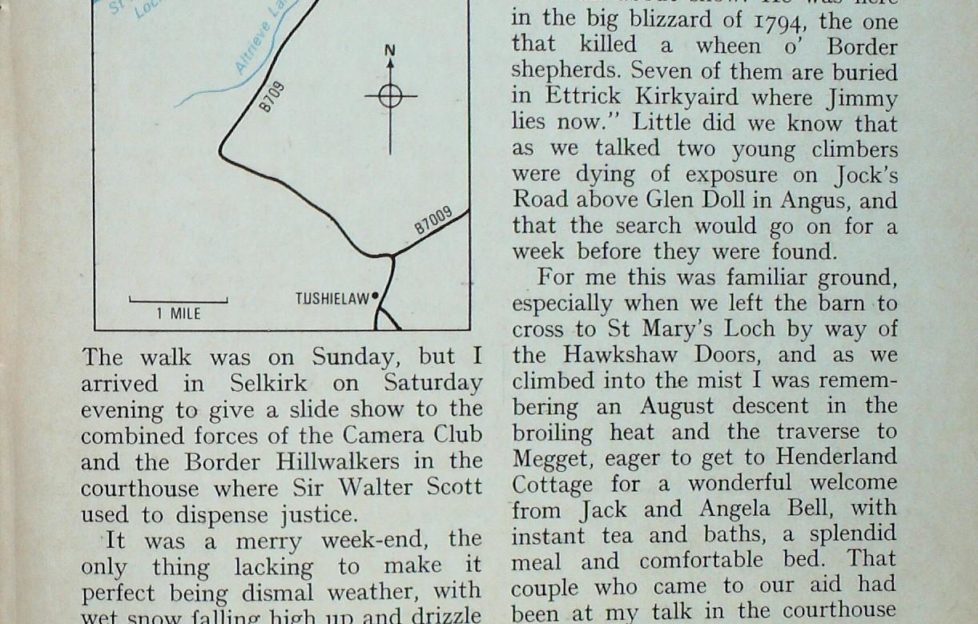

The walk was on Sunday, but I arrived in Selkirk on Saturday evening to give a slide show to the combined forces of the Camera Club and the Border Hillwalkers in the courthouse where Sir Walter Scott used to dispense justice.

It was a merry week-end, the only thing lacking to make it perfect being dismal weather, with wet snow falling high up and drizzle lower down. Nor had it improved on Sunday when about 30 of us headed north up a green shoulder into the snow and mist, while the remainder of the party set off on a more ambitious round over the tops. I chose the passes rather than the white-out higher up, striking out from the Gordon Arms to make a climbing traverse of about four miles and drop into a green oasis where the Douglas Burn foams past Black- house Tower, and farm buildings and drystone walls give a homely feeling to the rolling slopes.

Nobody lives here in winter now, it is too remote, but there was a warm hayshed for us to eat our pieces in. The barn, of course, was part of the farm where the Ettrick Shepherd worked for ten years, and only the previous night I had sat in his wooden fireside chair in Selkirk courthouse.

“Aye,” said Dave Fordyce, President of the club. “Jimmy Hogg knew all about snow. He was here in the big blizzard of 1794, the one that killed a wheen o’ Border shepherds. Seven of them are buried in Ettrick Kirkyaird where Jimmy lies now.”

Little did we know that as we talked two young climbers were dying of exposure on Jock’s Road above Glen Doll in Angus, and that the search would go on for a week before they were found.

For me this was familiar ground, especially when we left the barn to cross to St Mary’s Loch by way of the Hawkshaw Doors, and as we climbed into the mist I was remembering an August descent in the broiling heat and the traverse to Megget, eager to get to Henderland Cottage for a wonderful welcome from Jack and Angela Bell, with instant tea and baths, a splendid meal and comfortable bed. That couple who came to our aid had been at my talk in the courthouse the previous evening, and it was grand to see them again.

This time we dropped past Dryhope Tower to St Mary’s Loch to cross where the Yarrow emerges from the eastern end, and cold as it was, there was a feeling of spring with dozens of peewits tumbling and calling, their sounds half-drowned by the shrilling of curlews and the crying of gulls round a man ploughing regardless of the rain. Golden plover went whisking over our heads, too, joyfully burbling as they swerved about in a tight flock and then landing, showing off their ebony black bibs and golden backs.

Our route now was across the hill again, up over a little pass, to look down into new country, down into Altrieve Lake, the misleading name for a burn on the road to Tushielaw in Ettrick. Below us now was the farm where James Hogg died after his unsuccessful career as a sheep farmer, but brilliant one as a teller of tales, writer of songs and ballads, and a poet of the people second only to Robert Burns. I don’t see him as a distant figure, for he died in 1835 only 50 years before John MacDougall was born.

Now we dropped to the swollen burn, crossed it with difficulty, and swung back to the Gordon Arms in good time to get changed. But before we settled into the hotel the club book was examined by the two leaders to see that everybody who had signed out that morning had signed in, an important precaution when you have fifty people of all ages from school children to pensioners on a cross-country walk.

In fact, 62 of us sat down to the meal, which was about twice as many as at an average meet, these being held once a fortnight. And I am a member of the club now, having been elected for life. At the dinner I had the honour of being nominated into the distinguished company of “Plodders,” of whose existence I had heard nothing until Dave Fordyce and Ross Brownlee put me in the picture as they presented me with the official tie.

Ross was the spokesman. “This tie,” he said, “has a date on it, 1645 when Montrose crossed the Minchmuir after his defeat by the Covenanters at Philiphaugh. And the crest below the date shows a pair of boots, sprigs of heather, with the word Minch for Minchmuir and at the bottom ‘The Plodders’. You earned this tie by crossing the Minchmuir when you walked from Galashiels to Moffat. Your wife will get a scarf. A book is kept at Philipburn Hotel to sign by anyone who has walked the Minchmuir. The tie has the words on it ‘Selkirk – Innerleithen.’ The book for signing used to be kept at Tweedside Hotel, Innerleithen, but it was thrown out by a new hotel owner. The records were lost, but we think there are about 1000 Plodders. We hope the pair of you will wear the tie and scarf and come back often.”

After that little ceremony and the serious business of tucking away a a fine meal, piping hot and ably served, we had some entertainment with genial secretary J. B. Baxter at the piano and the distribution of song sheets of Border ballads and weel-kent melodies. We had a recitation or two, including Tam 0′ Shanter from our pianist, ably prompted by the audience when he was stuck for a line, but any wee halt didn’t dampen his fervour!

We’ll certainly be back, and I intend to keep a date with Ross Brownlee when he is going to show me some kingfisher haunts. The kingfisher is a favourite bird of mine which I would travel a long way to see, for it has become such a rarity in Scotland. And he is going to show me the best place for badgers in Selkirkshire.

And I shall be keeping a date with Dave Fordyce, too. In May he is going to take me on his favourite walk in all Scotland.

Footnote . . .

Tom Weir wishes to thank Professor Alcock for allowing him to draw on the typescript of his unpublished paper The Auld Wives’ Lifts: A study in antiquarian taste and perception.

You can read more of Tom’s escapades here, and a new column is published online every Friday.

More from 1975

More from 1976

- May 1976: Secrets Of The Muir

More instalments every Friday