Tom Weir | Two Lucky People

In October of 1975 Tom Weir had some words of inspiration for old friend, and former RSPB Director, George Waterston OBE

How would Waterston or Purchon

Like a bird to do research on

The way in which they propagate

their clan ?

Thank the Lord the bugle’s callin’

And they’ll have to go and fall in

Now for twenty minutes’ love

life while we can.

THESE lines, written in a prison camp in Bavaria in 1943 made George Waterston smile when I quoted them to him.

“Where did you dig that up ?”

And recollections began to flow when I told him I quoted it from Bird Watching — The Song Of The Redstart, written by fellow officer R. D. Purchon to cheer up the camp inmates who had been press-ganged into all sorts of ornithological services.

“I’m the luckiest chap in the world,” said George. ” Even when taken prisoner after the battle of rete in 1941 I landed on my feet amongst a fine bunch of naturalists. Purchon was studying swallows and held crickets, John Buxton wrote a book on redstarts as a result of his work, Peter Condor, now -Director of the R.S.P.B., was studying goldfinches, and I was busy on wrynecks. In fact, some of my wrynecks were driving out the redstarts from nest boxes we had made for them.”

I prodded George to tell me some more.

” Well, it was there that Ian Pitman and I began thinking about Fair Isle, and how marvellous it would be if we could get a bird observatory on the island. Planning to buy Fair Isle and do some real scientific work up there to unravel the mysteries of bird migration, was a way of escaping from the camp into the freedom of the future.

“ Getting a chance to do so much birding in the camp whetted our appetites, for so relatively little was known about the detailed lives of individual species. Even in camp we made contact with German ornithologists. I had records of German bird notes sent to me by Professor Erwin Stresemann. I sent him my notes on the birds of Crete, and when he published them along with his own in the middle of the war in a German journal he acknowledged the help of a certain Lieutenant Waterston.

” Funny how things work out. When Crete was retaken by the Allies, Heinz Seilmann, the great German cameraman, was captured. But when he explained he was filming the life of Eleonora’s falcon, he was allowed to go back and finish his work.

” Imagine it, years later in America, Professor Stresemann, Seilmann and I faced an audience from the same platform at an International Ornithological Congress. And when Stresemann stood up to give his address, he introduced us : ‘On my left George Waterston, and on my right Heinz.’ Then he told the story of our adventures in Crete and how our friendship through birds triumphed over the stupidity of war.”

George’s brown eyes fairly sparkled in his dark gipsy face as he spoke of how the “ups ” of life so wonderfully make up for the ” downs.” It was ill health which caused him to be sent back to Britain for hospital treatment in 1943. His homecoming was by way of Sweden and the-coast of Norway, then west across the North Sea.

“The tears ran down my cheeks”

” I think the most emotional moment of my life was when somebody shouted ‘Land ahead,’ and there, only two or three miles off, was the Sheep Rock and Fair Isle standing out in the sunshine. The tears ran down my cheeks—I knew it so well, and it had been so often in my thoughts.”

George’s interest in the three- mile-long island lying midway between the Orkneys and the Shetlands had begun in the mid-thirties when it then held 130 folk.

“Oh, they were great fun, always good for a laugh, and really keen on birds, for it’s such a marvellous place for migration. Anything can turn up there.”

But Fair Isle had to wait mean-time, as the ship bore home and he went into hospital for kidney treatment. He was expecting to be given a Home Guard command when he came out, but instead found himself being persuaded by ornithologist James Fisher to under-take a study of rooks to assess their effect on agricultural output at a time when Britain was desperately short of food.

So from being a prisoner ornithologist, George was now a free professional, meeting farmers and leading scientists and building up a picture of the rook population and their feeding habits. Evidence that has built up since George’s confirms his finding that any harm that the rook does to crops is counterbalanced by the pests it eats.

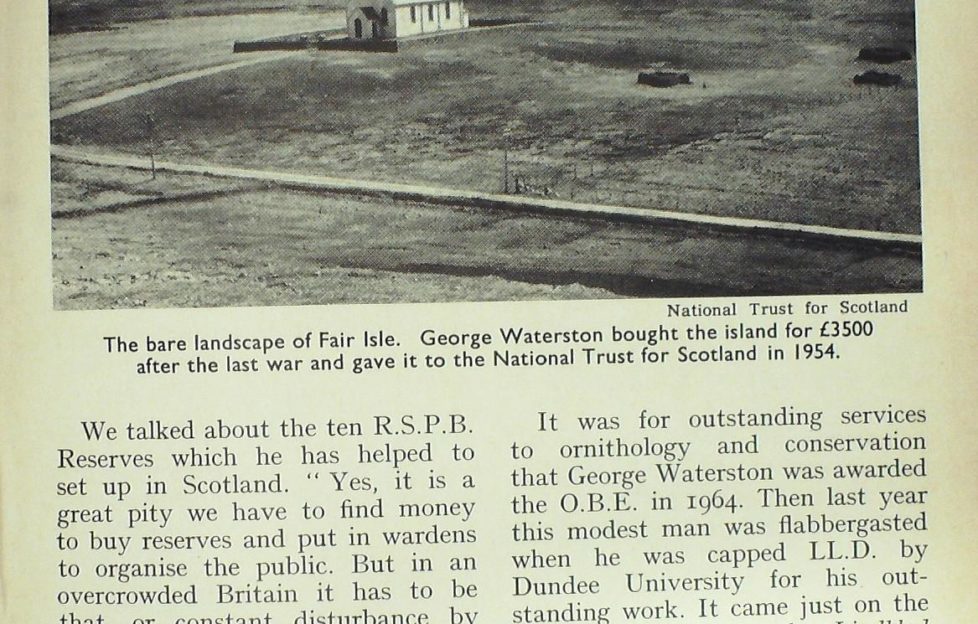

The end of the war saw George back in the Edinburgh family business of stationery and printing, but his heart was not in sales management. The Fair Isle dream was as fresh as ever. Typically he had prepared a careful memo stating the ornithological objective and presenting it to friends and likely people to win their backing and some of their cash. The purchase price of £3,500 was raised and George became the owner of Fair Isle.

There was a hutted camp on the island, built for the Navy, which was to become home to the noted ornithologist Kenneth Williamson. His work there soon proved that the island was even more remarkable for migration than anyone suspected. Visitors stayed at the observatory and stimulated the demand for knitting Fair Isle patterns. The “laird,” who had stayed in every croft, was ” George ” to all the islanders through his hundreds of visits. However, he could not close his eyes to the fact that, even since the purchase of the island in 1948, it was running down; crofts were deteriorating as young folk left and the population eventually dropped to under fifty.

Money would have to be spent on it to prevent it from becoming another St Kilda. Houses needed modernisation, a better harbour was an urgent need. The island needed a new boat and better roads. The solution was to offer Fair Isle to the National Trust for Scotland since they were in a position to launch an appeal to charities and the public.

Rejuvenating Fair Isle

The Trust took it over in 1954, with George as their official “visitor” or adviser, and great work has been done since then, thanks to financial help from the Scottish Office, the Highlands and Islands Development Board, the old County Council and Scottish National Trust staff helped by International Voluntary Service and Enterprise Youth workers. An airstrip has been built, renovated houses have electric light and the new island boat can come into a deep-water pier for the first time in history — previously a flit boat had to be used. Better still, there has been a drift back to the island by the young, and the population has stabilised at around seventy.

And in the year the National Trust for Scotland took over responsibility for Fair Isle, George broke with the family business of George Waterston & Sons to become secretary of the Scottish Ornithologists’ Club and Scottish Representative of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.

” Yes, there was some opposition, for I was the sixth generation in the oldest family firm in Edinburgh—it was established in 1752. I can understand their concern, for financially it didn’t look very wise.

” Nobody could have foreseen then the rapid growth of bird interest or the urgent need for action to combat toxic insecticides which were poisoning our birds of prey. And the nesting of the ospreys on Spey- side did a lot for us. Remember, you helped to guard the original pair in 1959 when we could muster only six watchers. Last year we had over a dozen breeding pairs, and we have had over 70,000 visitors at the Loch Garten hide in one year.

” Look at the Scottish Ornithologists’ Club. When I helped to found it in 1936 we could muster only sixty members in the whole of Scotland. Now we have 2700. It’s fantastic.”

I remembered the young black- haired George of these early days on the occasions when meetings were held in a Glasgow hotel. A hearty laugher with the gift of putting everyone at ease, his drive and enthusiasm was persuasive. Even at school in Edinburgh Academy it was natural that the bird club should meet in his house, talk ornithology and plan week-end outings. The accent was on conviviality.

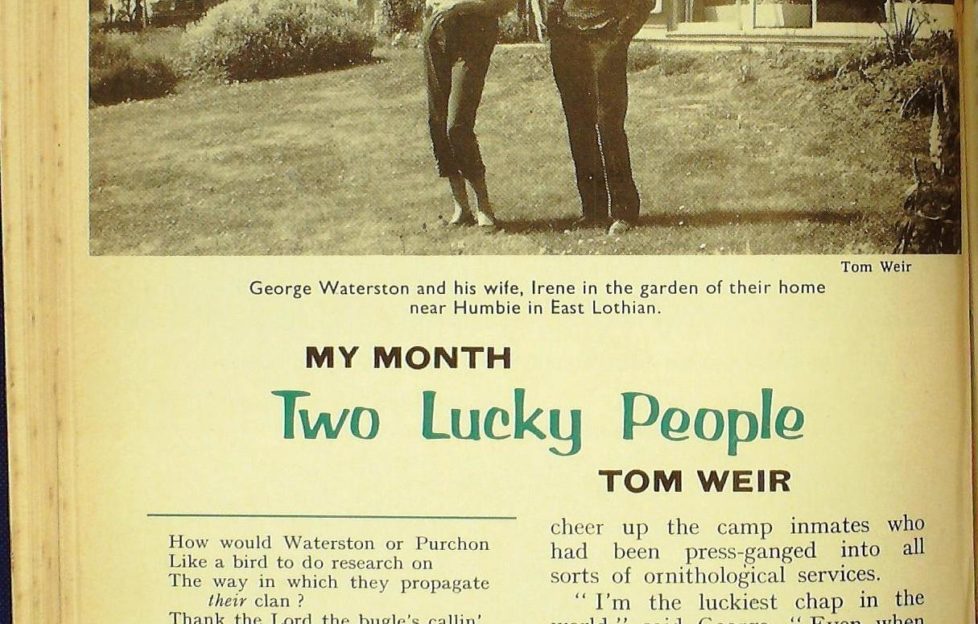

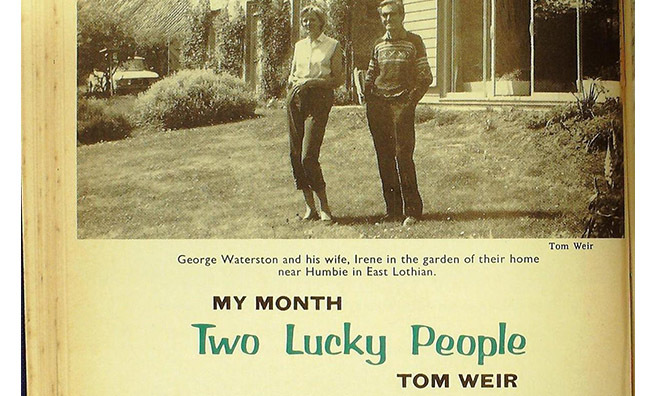

” After the stir of Edinburgh we really enjoy living full-time in the country. Irene and I are both fond of gardening. Planting things and we are trying to be as self-supporting as we can. Come and look.”

I was impressed by the amount of work they had done between them as we looked at the orchard, the neat vegetable plot and the flower garden.

” This place used to be a croft with a cow and hens on three acres. Part of the house was a wee shop. We bought it eighteen years ago for Irene’s mother with a view to having it ourselves eventually. We moved in last year after she died at over ninety.”

I congratulated them on their foresight, with country house prices the way they are now, when the setting can cost as much as the house.

” Yes, we got it for less than £1000—and look at the view !”

I told him I had never seen a more rural corner of East Lothian, with a burn meandering at the foot of the garden slope, and a swell of green hillside rising on the other side of the little valley. No sound of traffic or any other house in sight.

An album of memories

” I’d be nowhere without my wife Irene. We’ve worked together on everything, and we have had so many tricky problems and exciting times. Last year was terrific. We had the good fortune to be asked to go as guide-lecturers on the Lindblad Explorer for two months on a sail of 7000 miles.” And as he spoke he took down from the book-case a fat photographic album, showing me colour prints of the ship beset in the pack-ice of the North Magnetic Pole.

” The passengers were paying up to £1300 a month to be taken to the remotest shores of the Arctic. It cost us nothing and was a fantastic opportunity to see new places and revisit old Greenland haunts. 1 won’t forget the sight of the calving grounds of the beluga whales where about a hundred of them swam about with their six-foot calves. We enjoyed every minute of it even if it was a different kind of scene from what we would have chosen for ourselves.”

The album pages flicked to Ellesmere Land.

” Now that really was to our liking ; just Irene and myself and the nearest humans to us 75 miles away. That was three years ago, when the Canadian Wild-life Service put an Otter aircraft at our disposal and asked us to carry out for them a seven week ecological survey to report on what effect oil developments there would have on the musk ox and caribou lands. Irene found two plants new to Ellesmere.”

Other photographic albums were pulled out, one of a West Greenland trip in 1965 with a Danish expedition when they visited Cape Shackleton where a million pairs of Brunnichs guillemots form the biggest seabird colony in the world.

” We ate some of them, too,” grinned George, ” but we liked the tystie best, stewed in an iron pot.”

There were photographs in which I had played a part, at the ospreys’ eyrie in 1959 when there were only six of us to do a round-the-clock watch. A photo shows George with a string attached to his wrist as he takes a nap. The string was attached to me in the hide. At a tug from me he would raise a general alarm, since a tug meant an attempt was being made to rob the nest. Alas, that first nest was robbed despite our safeguard, and the raider got away after substituting hens’ eggs in the nest.

It was after that robbery the hide was thrown open to the public.

“Colleagues thought it was a rash decision when I said we should invite visitors to come and see the ospreys. Response was fantastic. It did more good for conservation than almost anything else we could have thought up. We have had over 70,000 in one year and quite a number of them have joined the R.S.P.B.”

Wonderful how Irene has shared his experiences with him. She, too, is a keen ornithologist, but has been taking more and more interest in Arctic botany, perhaps as a relief from constant birds since her job was secretary of the Scottish Ornithologists’ Club when George took over full-time Directorship of the R.S.P.B. in Scotland.

I remembered her with a big book on alpine plants at the hide in Fetlar when the first pair of snowy owls nested, making it a first for Britain. Protection was vital, so George was there mustering a guard of helpers, as he had done with the ospreys. Glad to say the Arctic owls are still nesting after eight years, and the Fetlar hill has Reserve status.

We talked about the ten R.S.P.B. Reserves which he has helped to set up in Scotland.

” Yes, it is a great pity we have to find money to buy reserves and put in wardens to organise the public. But in an overcrowded Britain it has to be that, or constant disturbance by large numbers of people would drive away what bird watchers want to see. And valuable habitats are so vulnerable to commercial exploitation. Right now the Society are trying to raise £290,000 to buy the whole 1500 acres of Loch Garten to protect the total forest environment of that wonderful bird country.”

And with a swift motion he passed me an “appeal” form. The old fund raiser was still very much in action!

The “ups” in life so wonderfully make up for the “downs”

It was for outstanding services to ornithology and conservation that George Waterston was awarded the O.B.E. in 1964. Then last year this modest man was flabbergasted when he was capped LL.D. by Dundee University for his outstanding work. It came just on the eve of departure on the Lindblad Explorer. Alas, things were never to be quite the same afterwards, for around last Christmas he had a return of the old kidney complaint, suffering pneumonia and pleurisy as well.

For two months he lay in Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, weak and depressed. I knew he was seriously ill, but I also knew that he didn’t want anyone to hear about it. He cannot go on any long trips now for he is tied to a kidney machine in Edinburgh Infirmary, which he has to visit three nights every week for five hour stints. “A tedious bore and very time- consuming,” was all he would say about it.

He looks upon the restrictions imposed upon him as an exercise in adaptation. Depression has gone and his natural ebullience and enthusiasm for life has returned.

“I have a lovely place to live, plenty to do and I can lead a pretty normal life. I’m lucky,” he says.

Lucky he is, certainly to have achieved so much in his most active years against a background of the kidney trouble which has plagued him since boyhood. Lucky to have retained his youthful enthusiasm for all the things he holds dear. Not so many manage to do that to the age of 64. His beloved Fair Isle has been uppermost in his mind recently, because he sees a threat to its survival if the Loganair inter-island service is withdrawn as is being suggested.

George explained to me why the present air service is so vital to the Fair Isle community.

“The economy of the island depends in part on the visitors who fill the 24-bed hostel, which is part of the new observatory we built in 1969. To keep the hostel filled we need the Loganair service, since the boat could never carry enough passengers to make the observatory pay its way. Because of the observatory the islanders have a good market for their produce. It is also their community centre. It cost £50,000 to build.”

Explained this way, I could see why he was concerned. He had just written out a personal appeal asking people to support the National Trust for Scotland in giving a donation to further the work of bettering the island for the crofters, who are putting the land into better heart by reseeding the rough pastures.

Speaking about the future for himself, he is keeping his eye on a glimmer of light.

“My hope lies in a kidney transplant, and I am pressing hard for it.”

The problem is to obtain somebody’s kidney.

“I know of transplants which have restored people to complete normality once the body has adapted. Meantime, I can do most things except heavy work. I drive myself from here to the Unit in the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary and connect myself up to the machine. And while my blood is being changed I watch television. It’s about all you can do, for you feel too light-headed for reading. I go to bed in the Infirmary after it, then drive home.”

I declined their warm invitation to stay the night, knowing that George has only one clear day to himself between drives to the Infirmary. I made up my mind, however, that I would dedicate my own kidneys for use to help someone like him. Even as I made the decision I had to chuckle, for such is George’s power over people, that I could almost have passed him my kidney there and then.

* * * *

Post Script:—Soon after I wrote this article I heard that George Waterston had been offered a transplant operation and had jumped at the chance. Unfortunately, it did not work out satisfactorily and his system rejected it. However, the surgeons have offered to try again at the first opportunity and George, warrior that he is, is raring to go.

For more of Tom’s columns check back here every Friday.