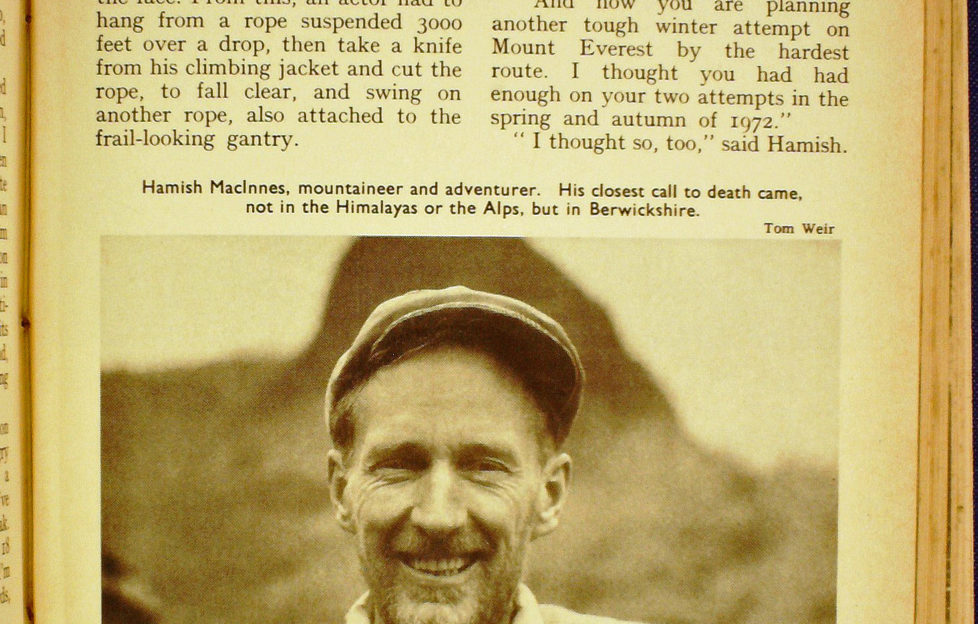

Tom Weir | The Sage of Glen Coe

In March, 1975, Tom Weir met with a kindred spirit, Hamish Maclnnes, the Sage of Glen Coe . . .

I AM not a pessimist, but I couldn’t help wondering if I was wasting my time as I packed crampons, ice-axe, head torch, gaiters, climbing helmet and other gear. For the rain was battering on my window, and the weather forecast promised nothing better in the next 24 hours.

I was bound for Fort William, to give a lecture, and Fort William and Ben Nevis go together. There was plenty of snow on the Ben, and I had thought it just possible that there could be an overnight change, not only in the overhead conditions, but in the watery eyes, running nose and spluttering cough which were giving me a below-par feeling.

So off I drove after lunch into premature darkness up the side of a Loch Lomond half lost in the gloom of pressing rain clouds – clouds discharging ever more generous measure as I caught the full force of the wind on Rannoch Moor. Then a lift to the spirits as the Buachaille hove into view, its black wedge standing up like a rock skerry amidst a turmoil of vapour bursting from Glen Etive around the lower crags.

Then through the jaws of Glen Coe for the descent through water- falls, spraying out of a gloom so dark that I had to switch on my headlights, though the time was not yet four o’clock. After winding round Loch Leven, half-blinded at times by the glare of oncoming heavy vehicles taking up most of the narrow road, it was a relief to get to Banavie and relax in the house of my host, Dr Allison, who promptly gave me a throat lozenge!

My slide lecture that evening was to the local branch of the Saltire Society. It was good to meet old Lochaber friends. It was good, too, to get to bed at half-past midnight and know no more until a rap on the door in the morning told me it was nine o’clock.

“See your doctor and get an antibiotic from him if you are no better by Monday,” advised Dr Allison. Meantime, I drove off up Glen Nevis in the unchanged weather, intent on having a walk through the gorge to Steall.

Even in a downpour you can enjoy the nobility of a place such as this, with the swirling river brimful and spray from it shooting up like steam. This was the spectacle around Polldubh, where the crags close in and the road is forced across to the north side of the glen. And it was just short of here I overtook a smartly-dressed gentle- man in city suit and raincoat. He carried a sizeable parcel, done up so that it could be gripped like a case.

As I stopped to offer him a lift, I thought it strange that he wore no hat on a day like this.

“Thanks, thanks, but I want to walk,” he said in a curiously strangled voice. I drove on, assuming that he must ‘be walking no farther than Polldubh. I had forgotten him by the time the great water-slide of the Allt Coire Eoghainn came into view, a virtual avalanche of white pouring I200 feet down the gorge wall. That cataract descends the longest and steepest grass slope in Britain, at an average angle of 35 degrees. The actual slide is I500 feet, but the slope goes on right to the top of lien Nevis. I once climbed up all the way, and once was enough!

Donning an anorak and water-proof trousers, I took a wee walk along the high path, just to relish this most Himalayan of Scottish gorges. It could almost have been the Rishi itself, and Stob Ban, with its snows, and the clouds scudding amongst its crags, Nanda Devi. All scale is relative, and everything here, the Caledonian pines, the birches, the rowans jutting askew from the crags hemming the thundering river, is in perfect unison, made even more splendid where the Steall waterfall comes into view, blocking the mouth of the gorge in a 350-ft. spray of noble waterfall.

Turning back after that sight, I was soon at the car park and driving down the road again when who should I see trudging steadily towards me but the bare-headed city gent with the parcel. I nearly stopped to offer him my spare hat, if only to find out where he was going, for there is no house other than the Steall Hut, so I can only conclude that this was his destination, perhaps to deliver a parcel to climbers in residence. Yet if that were so, why had he spurned my offer of a lift? Whatever the truth, I hope he had a change of clothes waiting for him, for he was going to need them.

Home, I decided, was the place for me, and despite the foulness of the day there was a queue for the Ballachulish Ferry, so I had time to look at the progress of the bridge as I waited. It is steadily pushing out from both sides, and will soon be meeting in the centre. Forty minutes, and I was over the other side, turning into Glen Coe and knocking on the door of a freshly white-washed farmhouse called Achnacon.

To my delight, the man himself answered it, Hamish Maclnnes, lean, lanky, a slight touch of ginger in his wispy beard, and a smile of welcome breaking his normally slightly serious expression.

“Great to see a friend. You’re just in time for some coffee. I’m just down off Buachaille Etive Beag. Didn’t go to the top, though. Too wet, nothing to see.”

“Don’t tell me you were climbing for pleasure today?” was my response.

“No, not for pleasure. Just to keep fit. It was great a week past Friday, plenty of snow, and we cramponed up the Curved Ridge, really good. On the Saturday I was on Bidian nam Bian looking for ice to test out the crampons properly. It’s a new design I’ve worked out, and I think it’s going to be good.”

I told him I had really called to congratulate him on a safe return from the bird-eating spiders, the tarantulas and the scorpions in the jungles and on the Great Prow of Roraima.

“It sounded terrible,” I said. “But your hook made a fine adventure story, and the television film was superb.”

“I think you would have enjoyed it, for the wild life was really fantastic.”

Hamish never tries to impress you. He tells his tales in bits and pieces so that you have to quiz him for details such as hunger, illness, hardship and close calls with death. So almost casually he told me he wasn’t doing very much just now except designing equipment for the winter attempt on Mount Everest and working on his novel.

“Yes, it’s an adventure novel set in Scotland, and it would never have been started if I hadn’t had that spell in hospital last summer. It’s maybe the closest call I’ve had to death.”

Then he told me a remarkable story almost stranger than fiction.

The train of events began at St Abb’s Head on the Berwickshire coast, when a drystone wall collapsed as Hamish scrambled over, and he took quite a bruising on the legs. One of the bruises had been punctured by a pointed rock, and it was so painful that he had difficulty in getting into his car.

Next day he had planned to go hang-gliding in the Pentlands (another “throw-away line.” I didn’t know he had built himself a hang-glider and was learning to fly it), but the friend who was to join him called off. So with time on his hands, Hamish decided to go along to Edinburgh Royal Infirmary and see if he had a broken bone, for the pain in his leg had worsened during the night and was beginning to worry him.

However, things were moving slowly in the Infirmary that day. Hamish waited and waited for his X-ray, finally got fed up and left. Now we come to the part where the Goddess Luck played her part. Hamish was kept in Edinburgh for a business appointment next day, so instead of driving off immediately to Glen Coe, as he had previously intended, he decided to go back to the Infirmary and try again for an X-ray.

When the doctor in the Casualty Department saw the X-ray plate she recognised on it a tiny pocket of gas gangrene. Instantly she called in the surgeon.

Hamish had a shock coming to him. The surgeon did not pull his punches.

“We’ve had three people in here with gas gangrene. Two of them died, and the other lost a leg. We’ll have to act immediately, for even the time it takes you to drive from here to Glen Coe could make the difference between saving your leg and losing it. And once the infection spreads beyond the limb, nothing can be done. So it’s a good job you came here today.”

The stone which had punctured the bruise had carried the infection, probably on bird droppings. And I could echo Hamish’s feelings when he said thoughtfully, “It’s quite frightening to know this can happen.”

The surgeon had told him that gas gangrene was a common cause of death by bullet wounds in World War I. Thanks to antibiotics and penicillin drugs, its effects can be arrested today, and, fortunately, the tissue-destroying gas shows up on X-ray plates.

Hamish showed me the scar on the region of his shin bone, an angry oval of red flesh.

“I’ve made a metal plate to put over it, for I’ve got to see the skin doesn’t break. l began the novel during the 18 days I was laid up in hospital. I’m enjoying it. It’s over 80,000 words, and it isn’t finished yet.”

After that came the next throw- away line by the Grand Master. Not for nothing has he earned the title, “The Sage of Glen Coe”.

“Yes, it was handy to go right out to the North Face of the Eiger and get fit again.”

I waited as he said ruminatively, “Actually, it was mostly going to work by helicopter. But you did get a bit more climbing every day, so it was an easy way of getting back to fitness again.”

The “work” that Hamish was referring to was his part in the overseeing of the safety arrangements for the Hollywood sex, assassination and climbing film called The Eiger Sanction. Some of the action on the North Face involves a lot of falling, and this is where Maclnnes’s engineering skill came into play. For the most exciting incident he built a gantry projecting out over the face. From this, an actor had to hang from a rope suspended 3,000 feet over a drop, then take a knife from his climbing jacket and cut the rope, to fall clear, and swing on another rope, also attached to the frail-looking gantry.

“Bonington took a real fall while working on the film,” said Hamish. “Took a clean peel of twenty feet out on the face, but he went back up to his lead point again and got over it. Davie Knowles, who used to work with me in Glen Coe as a climbing instructor, was killed by stonefall on the second day of filming. I’ve lost a lot of good friends in the last few years . . .”

“And now you are planning another tough winter attempt on Mount Everest by the hardest route. I thought you had had enough on your two attempts in the spring and autumn of 1972.”

“I thought so, too,” said Hamish. “I was hoping to go to South America, but l became so involved in the designing of better equipment that I left l couldn’t refuse when Chris Bonington asked me to be deputy leader. It’s really interesting to try to beat the equipment problems Everest sets you when you have to go so far above 27,000 feet.

“None of the tents stood up to the conditions last time. I’ve designed a Super Box with curved hoops like the kind tinkers use in the Highlands, but with four longitudinal members bracing it. And as well as a strong outer covering, I have tried out a light- weight metal mesh to go over the top. It’s so strong that the biggest boulder I could throw down on it just bounced off. We’ll have better floor insulation, too. “

“I’ve also borrowed an idea from the old volcano kettle, where the heat is in the centre compartment and the water is in the jacket round it. I am trying out at dixie which fits on to the stove, but the heat goes into an empty cone of metal. You push the snow into the top, and it melts in contact with the hot cone inside, so maybe we won’t have to wait four hours for the stove to melt and boil water at a boiling point of 60˚C.

“The oxygen problem is interesting, too. I’ve been in touch with the Americans and the British Army, and we should have new-type cylinders 26 inches long by 4¼ inches in diameter, weighing only 10 lb, just half the weight and giving every bit as much oxygen as the old type. I’m having special valves made in the States, and I’m experimenting now how to get better control of the supply. The oxygen apparatus on the last trip was hopelessly inefficient.”

“Anyway, we’ll be trying all the gear when we go out to the Alps in January to camp high in the Mont Blanc area. For really big crevasses, I’ve worked out a way of jointing ladders and attaching down ward-pointing stays round which you can run a cable from both ends so that the ladders become one rigid bridge.”

For the new attempt there will be seventeen climbers, six of whom have been on the South-West Face before. Haston and Maclnnes will make a powerful pair, and two Glenmore Lodge instructors will be in the party, Peter Boardman and Alan Fyffe. Mike Thompson, who was with Maclnnes on Roraima, will organise the food, and after the starvation of the Lost World trip, it is to be hoped that the cuisine will be varied and plentiful.

As for the route, this time Bonington and Maclnnes are attacking the crucial rock band farther to the left, where they hope to be able to climb a snow-filled chimney at 28,000 feet and traverse right across the face to reach a gully giving access to the summit. The all- important thing is to be on the mountain as early as possible. It is hoped to have base camp set up by August 25, to give the climbers a chance to make the summit before the cold and the wind become too desperate for survival at these heights.

“Come over and see the workshop. You haven’t seen my new set-up. You know that my job is to design better equipment and work out improved techniques in rescue work, not only on mountains, but for, oil-rig and oil-platform rescues.

I thought what a lot had happened to Hamish in twenty-one years. He emigrated to New Zealand and opened up a lot of new routes there. Then he set off for Everest with Johnnie Cunningham, with only a few quid between them. Now he’s going back to try the most difficult way to the top of Everest, with the most expensive expedition ever mounted, costing £100,000 no less.

Hamish climbed with Chris Bonington when the latter was just starting his climbing career, and now the pair of them must be amongst the best-known and most respected climbers, writers and photographers in the world.

“Strange the way it works out,” Hamish responded to my comment. Then, as an afterthought, as I was about to drive away, he said, “I forgot to tell you. I was out on St Kilda last summer. Joe Brown and I were landed on Boreray to try the big pinnacled face that leaps 1,400 feet up to the summit. We thought it might give a great climb, but it was no use, really nasty, too much grass and too many birds, gannets all over the place. The big stac in Soay Sound is the one we would like to have done, but there was no time. The place I really want to go to most of all is the Trango Towers in the Karakoram. If Everest hadn’t come along I think Chris and I would have gone there. But it can wait.”

It was Tom Patey who first brought back a report on the Trango Towers. He reckoned they were the hardest-looking vertical faces he had ever seen. They will be Just right for Maclnnes and Bonington.

Check back here next Friday for the next instalment from Tom’s Archives…

More from Tom’s Archives

- March 1975: The Sage of Glen Coe