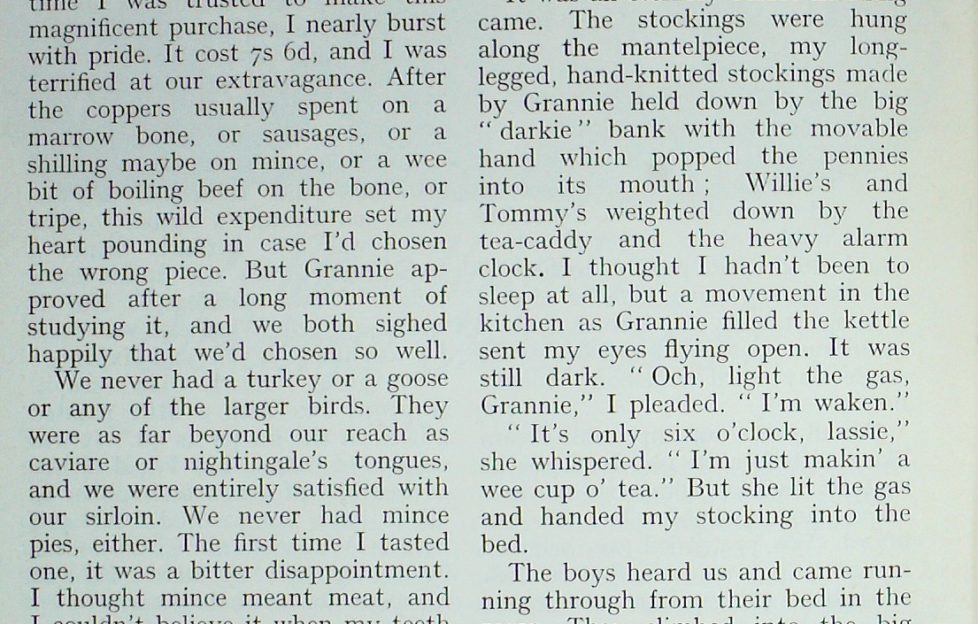

Days Of Christmas Past

Actress Molly Weir wrote this piece for us in 1968

on “those hard-up wonderful Christmases” of her

childhood – less extravagant, but no less cheerful

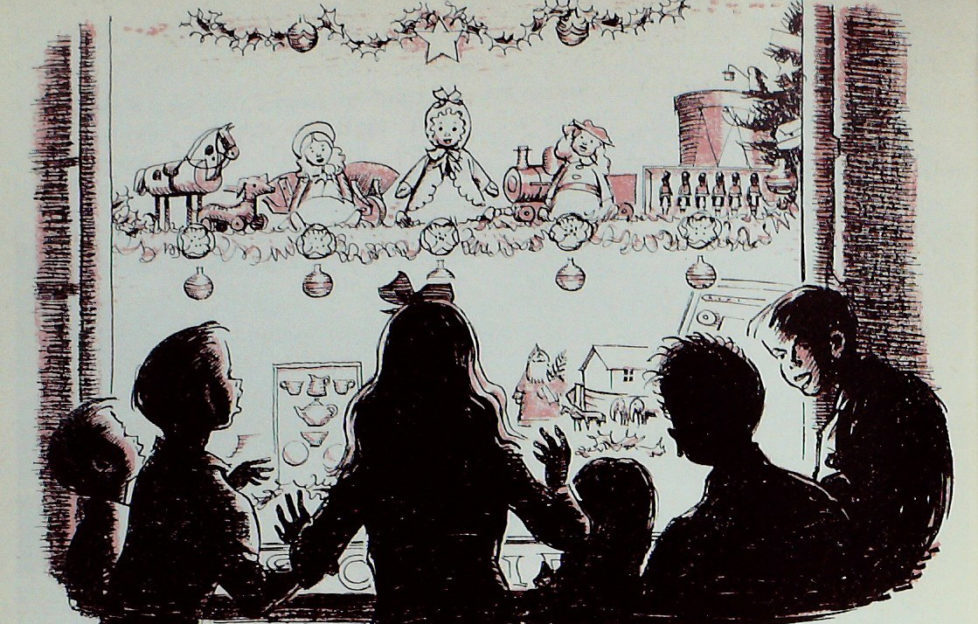

When we were children it was the windows of the big Co-operative up the road which told us that Christmas was near.

Nobody at home mentioned it, for when you were working on a tight budget, as my mother was, you didn’t go around encouraging your family to wild dreams of turkeys or walking dolls and steam engines.

You kept as quiet as possible and tried to forget the slimness of your purse, and that however many letters are sent up the chimney to “Santa,” few of the requests are likely to find their way to your room and kitchen.

But the shops arrayed temptation in every glittering window, and news would quickly spread as soon as the first spy noted the blinds drawn.

“The Co’s getting ready fur their Christmas windaes,” we chorussed to each other. “It must be gettin’ near time to send a letter to Santa.”

We wouldn’t send them, of course, until we’d seen what was newest in the way of toys and books.

Impossible dreams

We were in a fever of impatience for those blinds to go up, and raced up the hill every half-hour to see if we could be first to gaze upon the Aladdin’s cave revealed under the glittering lighting.

“Oh, isn’t that doll beautiful!”

I felt life could hold nothing better if only I could hold that perfect replica of a baby in my arms. But, of course, I knew it was impossible. Still, I could run up and admire her every single day until somebody bought her.

We all chose our impossible dream like this before we got down to the realistic level of things our mothers might, just possibly be able to afford. We pretended we believed in Santa, but we knew better than to wish for things of an extravagant nature.

But there were plenty of other delights, and in exuberant mood we’d choose about half a dozen gifts each, but always with a watchful eye on the price ticket so that we could throw out suitable hints for our mother’s consideration.

What sighing over the Meccano sets, the huge teddy bears, the life-like dolls, the boxing gloves, the football boots, the train sets, the scooters and skates!

Then, with the realism of tenement children, aware of values, we got down to concentrating on modest desires.

“Oh, yes, that wee box of paints at is 6d, that would be great, and it would go into my stocking, too.”

“Oh, and maybe that wee sewing set — I could embroider a wee flooer on Grannie’s apron.” How much was it? I nearly turned a somersault to see the upside-down ticket.

“Two shillings!” No, it was too much. What else was there for a shilling or one and sixpence ?

“Oh, gosh, I nearly didn’t see it. A pencil box with a little painted flower on the lid for is 9d.” It was empty, of course, but I had plenty of wee bits of pencil and rubber to fill it, and a treasured bone pen with a Waverley nib given to me by a neighbour for whom I’d run messages for a whole week.

Once we’d made our final choices, the letters to Santa started. Grannie was sure we’d set ourselves on fire as we leaned dangerously over the range and tried to float our little notes right up the chimney, for it was terribly bad luck if it wasn t wafted up first time and fell downwards into the flames. Grannie scorned such superstitious ways.

“Do you think Santy Claus kens whether yer letter fell doon or no’?” she’d demand. ” Awa’ tae yer beds afore ye burn yoursels.”

And as we protested and wanted to write more notes, she’d threaten — “Another word oot o’ ye and I’ll write a note to Santy Clans masel’ an’ tell him no’ tae bother comin’ near this hoose, for I’ll no’ clean the flues to be ready for him.” This was enough. We crept off to bed.

And then, there it was! Christmas Eve,

and time to hang up our stockings.

We had been on the go all day. I’d been sent down to the butcher for a piece of sirloin, Grannie’s favourite meat.

The first time I was trusted to make this magnificent purchase, I nearly burst with pride. It cost 7s 6d, and I was terrified at our extravagance.

After the coppers usually spent on a marrow bone, or sausages, or a shilling maybe on mince, or a wee bit of boiling beef on the bone, or tripe, this wild expenditure set my heart pounding in case I’d chosen the wrong piece. But Grannie approved after a long moment of studying it.

We never had a turkey or a goose or any of the larger birds. They were as far beyond our reach as caviar or nightingale’s tongues, and we were entirely satisfied with our sirloin.

My mother was always late coming home on Christmas Eve. She did the toy-shopping straight from work, and there would be a delicious rustling as she thrust her purchases into the press in the lobby before coming in for her tea.

It was an eternity before morning came. The stockings were hung along the mantelpiece, my long-legged, hand-knitted stockings made by Grannie; Willie’s and Tommy’s weighted down by the tea-caddy and the heavy alarm clock.

I thought I hadn’t been to sleep at all, but a movement in the kitchen as Grannie filled the kettle sent my eyes flying open. It was still dark.

“Och, light the gas, Grannie,” I pleaded. ” I’m waken.”

“It’s only six o’clock, lassie,” she whispered. “I’m just makin’ a wee cup o’ tea.” But she lit the gas and handed my stocking into the bed.

The boys heard us and came running through from their bed in the room. They climbed into the big bed beside me and we all dived into the stockings.

A wee toty doll for me that I could make clothes for. Lovely! A wee sewing set for making the clothes — my eyes sparkled over the coloured threads. A lovely big bar of chocolate, and right at the toe a tangerine wrapped in silver paper.

“Now don’t eat that chocolate afore your breakfast,” commanded Grannie, ” or you’ll be sick.”

As if I would! That chocolate was my treasure to be broken off and eaten piece by piece during the day, for as long as I could make it last. And I’d keep the tangerine for after my sirloin.

The boys put their new cowboy belts on over their pyjamas and fired their toy guns at Grannie and at me.

While we played, Grannie baked some scones and pancakes for tea. Soon my mother wakened and started to get ready for work, for, of course, there was no holiday on Christmas Day.

She looked up at the mantelpiece and said to me, “Have you looked up there yet ?”

I gasped. There, quite unnoticed from the bed, was a luxury I’d never dreamed of owning. I’d put it on my wee letter to Santa, but only as a fantasy. A little toy piano. And my mother had somehow found the money for it. And beside it, a set of toy soldiers for each of the boys. We could hardly speak for excitement.

Carefully Grannie reached up and lifted the treasures down, and I tried to play God Save The King from the dozen notes of my piano as the boys arranged their soldiers in battle formation.

Grannie sipped her tea and watched us with a twinkle in her eye. Oh, Christmas morning was more than lovely. It was perfect.

We had no tree or decorations, but we never missed them.

Tom Weir

Molly’s wee brother Tommy grew up to be a renowned explorer, Tom Weir, who wrote fantastic features for us on his adventures around Scotland.

You can find an online archive of them, here.