Tom Weir | In Border Country

In this column Tom discovers the wealth of history and remarkable landscape to stravaig in the Scottish Borders

As the roads get faster, that gentle country of the Borders seems closer. One hour from Edinburgh and you can be in Melrose in a swing down Lauderdale [or in Tweedbank now on the Borders Railway]. Or drive directly from Glasgow by Carnwath and Peebles and you have the pleasure of wide views stretching from Tinto to High Broad Law and its lumpy neighbours. I chose the latter route when I drove south to have an outing with the Scottish Borders Hillwalking Club before attending the annual dinner in the little market town in whose great abbey the heart of Robert Bruce is said to lie under the high altar.

Now it is all memory, and not just of a cold wind and blustery showers before a convivial evening. What I remember most vividly are the contrasts of sun and shadow, of racing clouds and moments of sudden illumination as the wine-red stonework of Melrose Abbey suddenly gleamed above the swollen Tweed, every intricate detail of its carving richly glowing.

Nor shall I forget the top of North Eildon and looking down on the showers sprinkling the Vale of Tweed in a fine mesh of gauze, suddenly lifted to reveal the pinnacle of Smailholm Tower on its crag and a patchwork of farmsteads glittering white in a setting of swelling fields and woods.

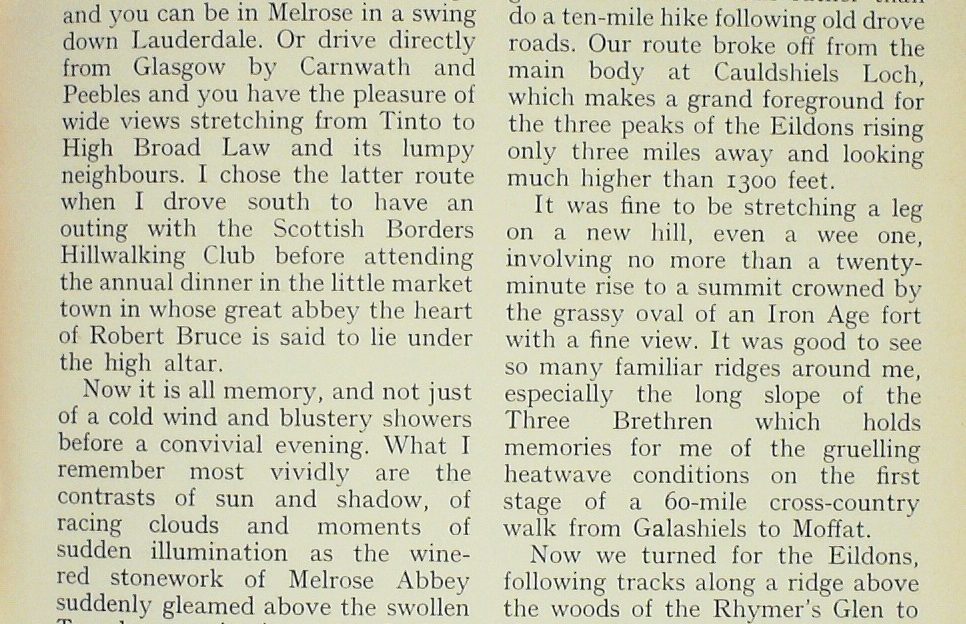

We had met at the car park that morning beside what used to be Melrose Railway Station — now a mouldering building — and of the assembled company of fifty or so, six of us had opted for a walk over grass and heather hills rather than do a ten-mile hike following old drove roads. Our route broke off from the main body at Cauldshiels Loch, which makes a grand foreground for the three peaks of the Eildons rising only three miles away and looking much higher than 1300 feet.

It was fine to be stretching a leg on a new hill, even a wee one, involving no more than a twenty-minute rise to a summit crowned by the grassy oval of an Iron Age fort with a fine view. It was good to see so many familiar ridges around me, especially the long slope of the Three Brethren which holds memories for me of the gruelling heatwave conditions on the first stage of a 60-mile cross-country- walk from Galashiels to Moffat.

Now we turned for the Eildons, following tracks along a ridge above the woods of the Rhymer’s Glen to Bowden Moor where a farm road strikes down to a wee loch on the Eildons, a good place for a picnic before striking up to the heather of the main peak at 1385 feet. As little volcanic peaks, the Eildons are second only to Arthur’s Seat and the Salisbury Crags in terms of character.

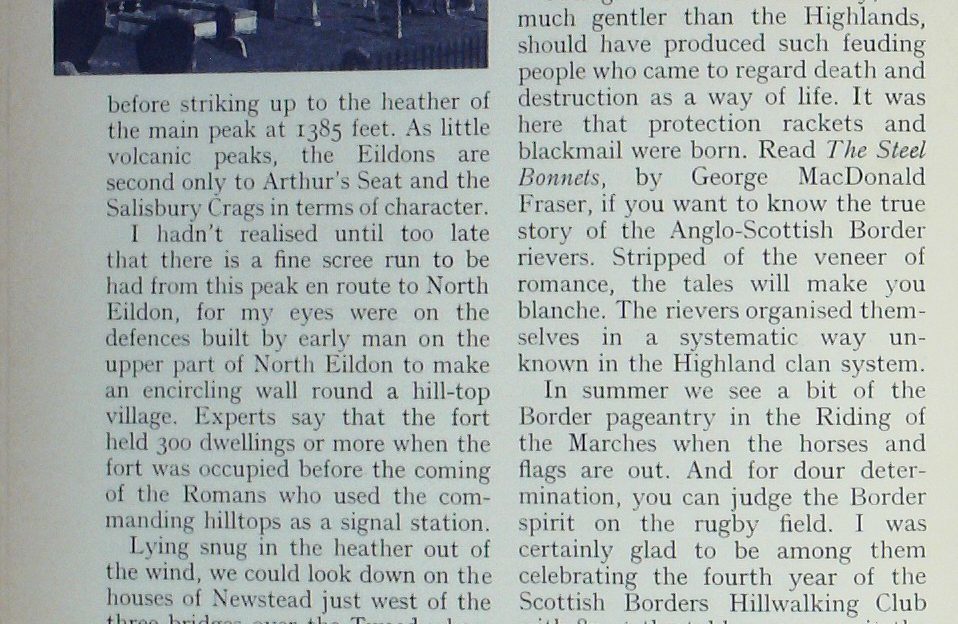

I hadn’t realised until too late that there is a fine scree run to be had from this peak en route to North Eildon, for my eyes were on the defences built by early man on the upper part of North Eildon to make an encircling wall round a hill-top village. Experts say that the fort held 300 dwellings or more when the fort was occupied before the coming of the Romans who used the commanding hilltops as a signal station.

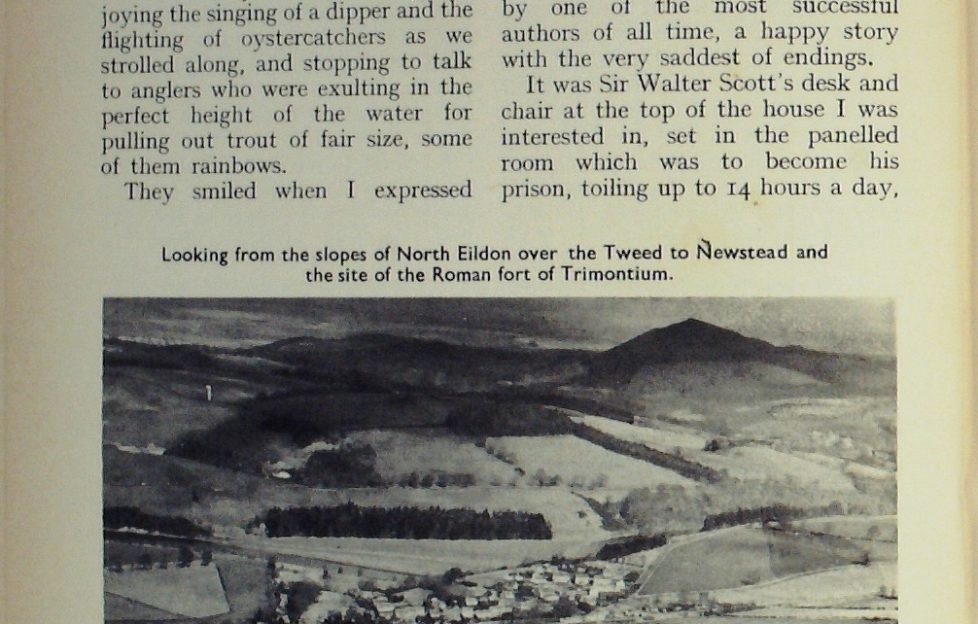

Lying snug in the heather out of the wind, we could look down on the houses of Newstead just west of the three bridges over the Tweed where the Romans built their fort and called it Trimontium.

Just over the river at Bemersyde was the view that Sir Walter Scott loved best, across the most enchanting sweep of the Tweed to the peaks on which we sat. And I could share his feeling because he had written about it so well, filling its landscape with the earth-poetry of its people. Even from where we sat we could see Carter Bar and the high blue ridges of the “Debatable Land” where for 300 years no one living there could feel safe in bed from Border raiders.

Strange that this country, so much gentler than the Highlands, should have produced such feuding people who came to regard death and destruction as a way of life. It was here that protection rackets and blackmail were born. Read The Steel Bonnets, by George MacDonald Eraser, if you want to know the true story of the Anglo-Scottish Border rievers. Stripped of the veneer of romance, the tales will make you blanche. The rievers organised themselves in a systematic way unknown in the Highland clan system.

In summer we see a bit of the Border pageantry in the Riding of the Marches when the horses and flags are out. And for dour determination, you can judge the Border spirit on the rugby field. I was certainly glad to be among them celebrating the fourth year of the Scottish Borders Hillwalking Club with 83 at the tables, nor was it the usual mountaineering club affair with toasts and formal speeches. Their dinners are more in the nature of ceilidhs, with songs and stories following one after another.

The most hilarious turn this year was an action-packed “Cornish Floral Dance” performed by three stalwart kilted worthies, clod- hopping and twirling as they turned the song into a version of an eight-some reel.

Nor could there be any show without Bob Service, as out he came to conduct community singing of well-known airs with much arm-waving and extravagant gestures, suddenly changing the mood when from out of his pocket he fished a piece of paper to read a touching poem he had written about his love for the Border hills and the people who live among them.

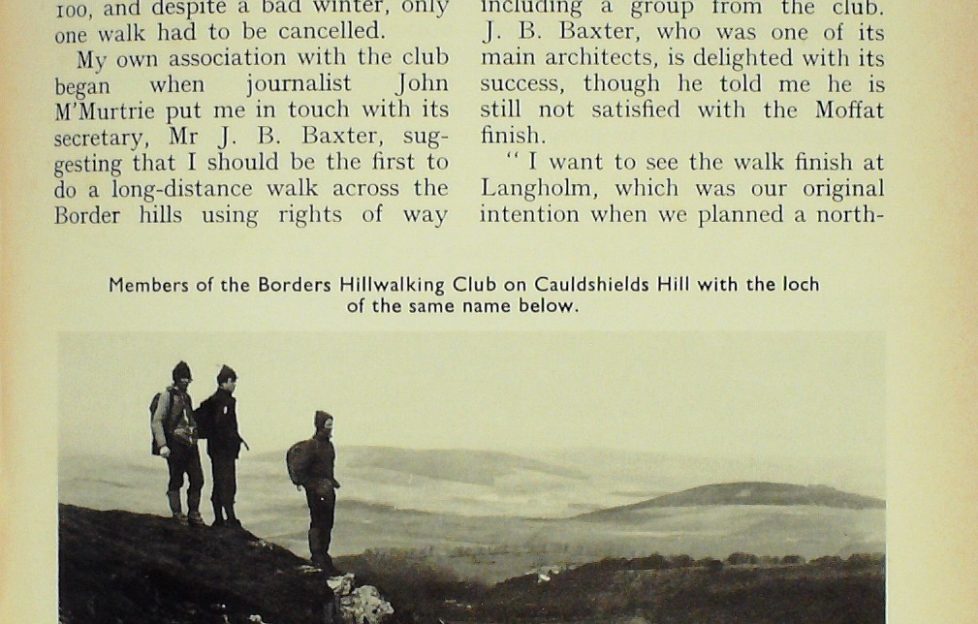

Bob is a pensioner who does a milk round and likes nothing better than to join the club on their fortnightly outings. Membership has now risen to nearly too, and despite a bad winter, only one walk had to be cancelled.’

My own association with the club began when journalist John McMurtrie put me in touch with its secretary. Mr J. B. Baxter, suggesting that I should be the first to do a long-distance walk across the Border hills using rights of way paths linking Selkirkshire, Peeblesshire and Dumfriesshire. Local groups had worked out the route, but no one had yet done it. My wife and I spent 3 and a half roasting days on it, and I told the story in the November 1975 issue of this magazine.

How had the 60-mile Border Walk fared in the interval? I learned that it was now a firmly established favourite, that something like a hundred wayfarers had done it, including a group from the club. J. B. Baxter, who was one of its main architects, is delighted with its success, though he told me he is still not satisfied with the Moffat finish.

“I want to see the walk finish at Langholm, which was our original intention when we planned a north-south route across the Border hills. But the landowners wouldn’t co-operate. I’m going to have another go at them to see if anything can be worked out, for the public demand for the walk is there.”

Baxter knows what he is talking about, for he has walked the Pennine Way in England and hopes to do the Cleveland Way shortly.

Me and I had a joyful little outing next morning, following the Ettrick to where it joins the Tweed, enjoying the singing of a dipper and the flighting of oystercatchers as we strolled along, and stopping to talk to anglers who were exulting in the perfect height of the water for pulling out trout of fair size, some of them rainbows.

They smiled when I expressed surprise at rainbow trout in the Ettrick, then gave me the explanation. The big flood which swept away the arch at Selkirk also overwhelmed a fish farm, releasing its captive rainbows to freedom in the river, to the delight of fishermen for miles around. We turned back short of Abbotsford, but I went to the turreted mansion later that day to make closer contact with the genius who built it by instalments as the money poured in from books written by one of the most successful authors of all time, a happy story with the very saddest of endings.

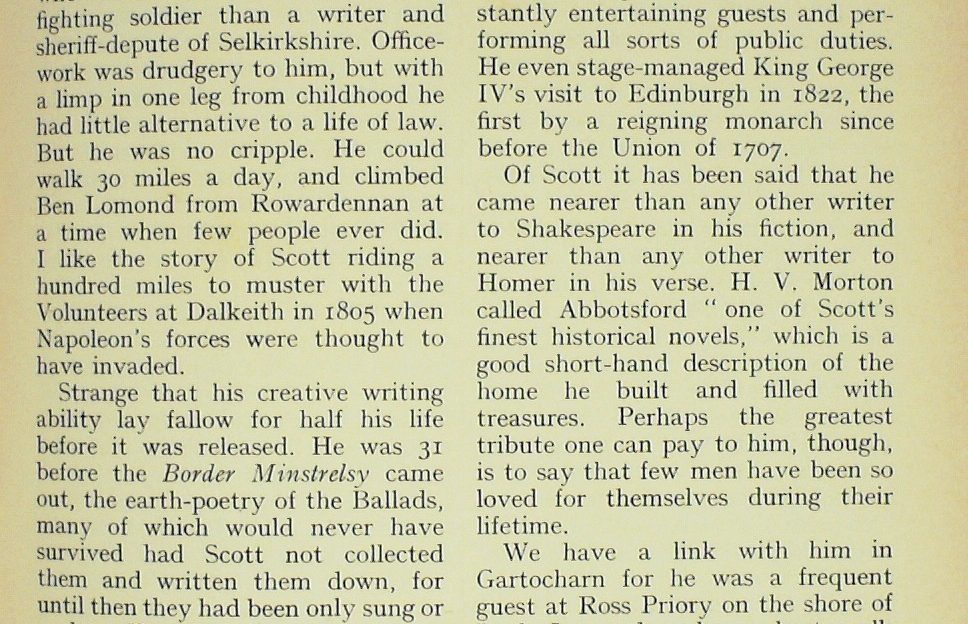

It was Sir Waiter Scott’s desk and chair at the top of the house I was interested in, set in the panelled room which was to become his prison, toiling up to 14 hours a day, writing, writing, writing, to meet a debt of £117,000. He was at the peak of his brilliance, and aged 55, when the financial crash came. At 61 he was dead, worn out by overwork, but he had paid back £80,000 to his creditors, and in time the full debt, was repaid from the books he left behind him.

The walls and turrets of Abbotsford rose above the Tweed by the financial success of these powerful works, yet he was a man of action who would rather have been a fighting soldier than a writer and sheriff-depute of Selkirkshire. Office-work was drudgery to him, but with a limp in one leg from childhood he had little alternative to a life of law. But he was no cripple. He could walk 30 miles a day, and climbed Ben Lomond from Rowardennan at a time when few people ever did. I like the story of Scott riding a hundred miles to muster with the Volunteers at Dalkeith in 1805 when Napoleon’s forces were thought to have invaded.

Strange that his creative writing ability lay fallow for half his life before it was released. He was 31 before the Border Minstrelsy came out, the earth-poetry of the Ballads, many of which would never have survived had Scott not collected them and written them down, for until then they had been only sung or spoken. He followed it three years later with The Lay of the Last Minstrel, and it was the success of these first books which swung him to partnership in the printing firm of James Ballantyne, whose financial failure 20 years later was to bring ruin and unhappiness to the author.

Small wonder when the crash came that he referred to Abbotsford as his Delilah, a temptress bringing us downfall, for he had lived beyond his means to raise a Gothic and Magnificent dream-house. Now he was shouldered with a monstrous personal debt which he had to pay off or surrender the mansion, the suits of armour, the heraldic shields, the weapons of war, the plate, the furniture, the innumerable trinkets and paintings. The only pledge he had to offer — his creative ability as a writer — and his creditors accepted it.

Wandering around looking at this extravagant museum of a place, I was thinking of the full life that Scott managed to live here, constantly entertaining guests and performing all sorts of public duties. He even stage-managed King George IV’s visit to Edinburgh in 1822, the first by a reigning monarch since before the Union of 1707.

Of Scott it has been said that he came nearer than any other writer to Shakespeare in his fiction, and nearer than any other writer to Homer in his verse. H. V. Morton called Abbotsford “one of Scott’s finest historical novels,” which is a good short-hand description of the home he built and filled with treasures. Perhaps the greatest tribute one can pay to him, though, is to say that few men have been so loved for themselves during their lifetime.

We have a link with him in Gartocharn for he was a frequent guest at Ross Priory on the shore of Loch Lomond, only a short walk from where I sit writing this, and in one of its rooms he wrote a bit of Rob Roy. Now I have a living link with the Scott Country for growing in my garden are a host of flowering plants presented to us by two members of the Borders Hill walkers as we drove away.

It must be old age overtaking the instinct which used to send me stravaiging at the sight of a spade, but since acquiring a new house with 1 and a half acres of mainly unbroken ground I am actually enjoying making the unproductive earth yield up a good crop of vegetables and a fine array of flowers.

I supply the brawn and my wife the brains, and it is great fun gathering the first spuds, watching the peas climb up the sticks, selecting our own lettuce and tomatoes, and, in season, hanging up a few strings of onions and stowing away a few jars of beetroot.

I have become an addict to “Gardeners’ World” on television, though cynical friends tell me I’d be cheaper to buy the vegetables as before and save myself a lot of work and trouble. I was even tempted to get some sheep or a couple of stirks for fattening, until my wife pointed out that if I wasn’t their prisoner she would be!

The best thing about my garden is the birds, a cock blackcap in May singing with a chiff-chaff among the alders above the burnside where my first find on return from the Borders was a hen mallard sitting on 13 eggs, and while I looked, a wee wren with a moustache of green moss was watching me, ready to fly with it to the nest it was building as soon as I disappeared. I have had a whitethroat jangling only a few yards away, and watched a hen pheasant lead a solitary chick across the lawn into our potato furrows.

In the summer evenings woodcock circle overhead on their strange, bat-like roding flight, sharing their patch with a hunting brown owl which dropped on a mouse as I watched it—the first time I had ever seen this species of owl make a kill. Sitting at the open French window one day, I had a grey wagtail dart into the room after a fly. But the most brilliant sight was a twittering flock of about 300 goldfinches fluttering like tropical birds as they circled between oak trees and hedgerows. Their target was the thistles on the farm field just across the road where they lingered for days.

At the moment the Loch Lomond shore at the Endrick has the sound of the Hebrides about it, with the wading birds in full cry, oyster-catchers, redshanks, curlews, peewits, the reeling vibrations of dunlin and the thin “sheeleeps” of ring plover. We have a pair of goosanders which I hope will nest and make history on our corner of the loch, and a fine thing is happening—the uncommon partridge is reappearing.

What a contrast there was between the green Border hills and the wintry Highlands which greeted me back home. I would have gone skiing but for a tender left leg resulting from torn muscles on Ben Vane when Iain McNicol and I had a great run down from the windy summit. I’d never felt better on skis or experienced better snow, but that fall, just short of the car, left me shaking and I knew I had done some real damage.

I should have rested my leg more than I did. Instead, I was out with the crampons and ice-axe on the north-east buttress of Stuc a Chroin on a marvellous Swiss-like day of Alpine conditions. Then a week later I was ski-ing on the Lawers range and the leg felt weaker as a result. So, learning from experience and taking council from my wife to take it easy, we drove north for the Black Mount to do nothing more adventurous than enjoy the Caledonian pines of Loch Tulla and walk up Glen Fuar.

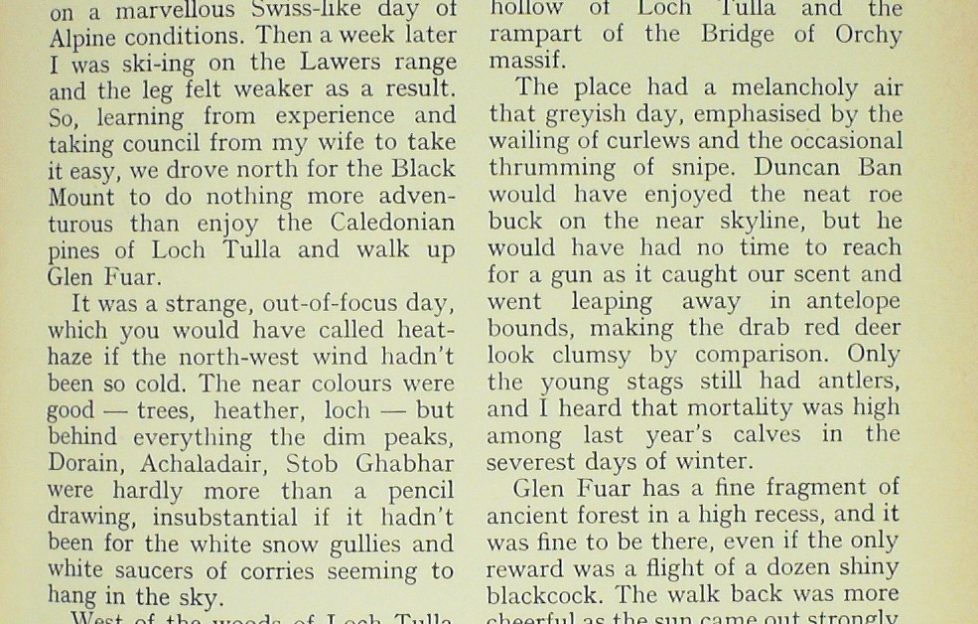

It was a strange, out-of-focus day, which you would have called heat-haze if the north-west wind hadn’t been so cold. The near colours were good — trees, heather, loch — but behind everything the dim peaks, Dorain, Achaladair, Stob Ghabhar were hardly more than a pencil drawing, insubstantial if it hadn’t been for the white snow gullies and white saucers of corries seeming to hang in the sky.

West of the woods of Loch Tulla is favourite walking country of ours. I’ve spent some of the happiest days of my life on its peaks, but nowadays I can get as much pleasure from its hidden glens and near ridges like Druimliaghart which starts up before you cross Victoria Bridge. Once it was the path to the house where Duncan Ban Maclntyre lived. This ridge has the ruins of an ancient clachan on it, and in one of the houses Fair Duncan of the Songs was born on a spring morning of 1724.

“The grey ridge” is still turfy green, though the biggings are mere foundations of stones. It is a place of great atmosphere, with the peaks of the Black Mount walling the sky on the north side of the ridge and falling away due east to the big hollow of Loch Tulla and the rampart of the Bridge of Orchy massif.

The place had a melancholy air that greyish day, emphasised by the wailing of curlews and the occasional thrumming of snipe. Duncan Ban would have enjoyed the neat roe buck on the near skyline, but he would have had no time to reach for a gun as it caught our scent and went leaping away in antelope bounds, making the drab red deer look clumsy by comparison. Only the young stags still had antlers, and I heard that mortality was high among last year’s calves in the severest days of winter.

Glen Fuar has a fine fragment of ancient forest in a high recess, and it was fine to be there, even if the only reward was a flight of a dozen shiny blackcock. The walk back was more cheerful as the sun came out strongly and sent skylarks singing and meadow pipits love-flighting.

We had a splendid drive back home in the light of a golden evening that cast its warmth on the point of Ben Lomond soaring above the Craigroyston shore. Its snow gullies were changing to pink even as we looked. We suffered a burst front tyre before we reached home, but even that annoyance could not spoil what had been a memorable spring day.

Read another great column from Tom Weir next Friday

More…

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archives of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly but surely getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here.