Land Of Hope And… Golly

“For me it had been a good summer.

To be truthful, I can’t really remember

a bad one, not in a country like ours

that has so many places that are so different…”

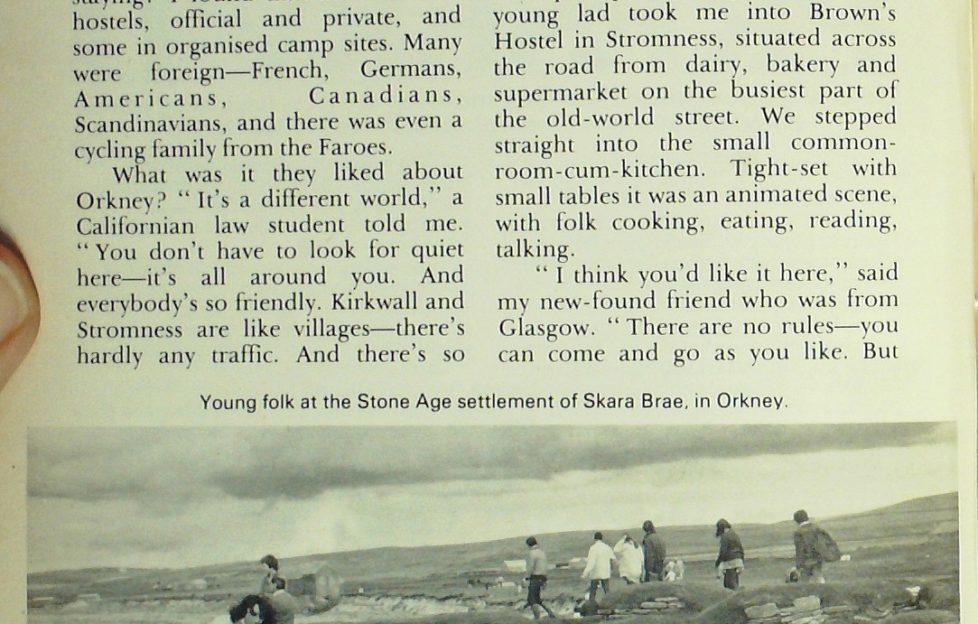

The biggest surprise I got in my three weeks on Mainland Orkney this summer was discovering its popularity with young outdoor folk. Kirkwall and Stromness seemed to be full of them.

Where were they all staying? I found that most were in hostels, official and private, and some in organised camp sites. Many were foreign — French, Germans, Americans, Canadians, Scandinavians, and there was even a cycling family from the Faroes.

What was it they liked about Orkney?

“It’s a different world,” a California law student told me. “You don’t have to look for quiet here—it’s all around you. And everybody’s so friendly. Kirkwall and Stromness are like villages—there’s hardly any traffic. And there’s so much to see—the cathedral, pre-historic burial cairns and the stone- circles, and the way the farms are built. There’s no poverty at all. This is how civilisation should be. They’ve got their values right in Orkney.”

A perceptive young man. Another young lad took me into Brown’s Hostel in Stromness, situated across the road from dairy, bakery and supermarket on the busiest part of the old-world street.

We stepped straight into the small common-room-cum-kitchen. Tight-set with small tables it was an animated scene, with folk cooking, eating, reading, talking.

“I think you’d like it here,” said my new-found friend who was from Glasgow. “There are no rules—you can come and go as you like. But anybody who is a nuisance is asked to leave—not by Mrs Brown but by the rest of us.”

I had a look at the dormitories and the showers. It was all good value at a price comparable with the official Youth Hostels.

The Stromness one has 54 beds and the one in Kirkwall has 100. There are other private hostels offering accommodation in Sandwick, Evie, Eday, South Ronaldsay and Hoy. In Birsay there is one that accommodates group-parties only.

Green Isles

On this visit I chose to stay on farms mostly, as a way of getting to know how the folk were faring on the most agricultural of all the island groups in Scotland.

The striking feature was the quality of the houses and the steadings. Modern machinery was everywhere and the whole land was greener than I remembered it. Nor was it imagination. New grass mixtures and clovers in conjunction with artificial manures, are enabling the land to carry more stock.

The demand for beef cattle is brisk, and the present stock could be as high as 110,000 for all the Orkneys, I was told by an island vet.

In the Kirkwall Creamery I was delighted to find that my old friend Alastair Whyte was still manager, having completed 27 years in the post.

“We have fewer farms supplying us, but they’re bigger, so we are producing even more cheese and butter than ever before and still winning prizes for quality,” he told me.

The statistics are that 65 farms supply about 14,000 gallons of milk a day in the summer, of which 10,000 are made into the famous Claymore butter, and 3,000 into Orkney cheese. It’s still not enough to meet the demand though.

Unlike Shetland the impact of oil on Orkney has been minimal since it’s virtually confined to the terminal at Flotta at the end of the North Sea pipe-line where the oil is stored for loading on to tankers.

The scale is small, and the economy has not been disrupted. The present fear of the Orkney folk centres on something else which could have a very damaging effect on their agriculture and way of life —uranium mining.

When the Islands Council banned exploration two years ago, and the objection was upheld by the Secretary of State for Scotland, they were safe from the threat. Not so. An attempt to bring in legislation against uranium exploration in Orkney failed in 1978, with the South and North of Scotland Electricity Boards objecting to the Council’s policy.

Orcadians number less than 18,000, and since almost every island has quantities of uranium, they fear their interests and way of life would be sacrificed if justifiable amounts of the nuclear fuel were found.

No right-minded person would deny the validity of their argument, but they represent a small interest when the EEC finances half the cost of exploration for uranium.

The Orkney Heritage society has published “Shout About It” leaflets, and a “No Uranium” delegation lobbied MP’s in Westminster during the summer. What a tragedy it would be if the economic balance of this happy and prosperous community were to be destroyed in this hideous way.

Sad thoughts to take away from islands that were looking their loveliest as I left the Bay of Skail and drove for a last look at Kirkwall with its cathedral and Bishop’s Palace where Haco, last of the Viking sea kings, died after his defeat by the Scots on the Clyde.

2016 Note: plans to open uranium mines were halted in 1980 after local campaigning, which included production of The Yellow Cake Revue on the subject by composer and conductor Sir Peter Maxwell Davies.

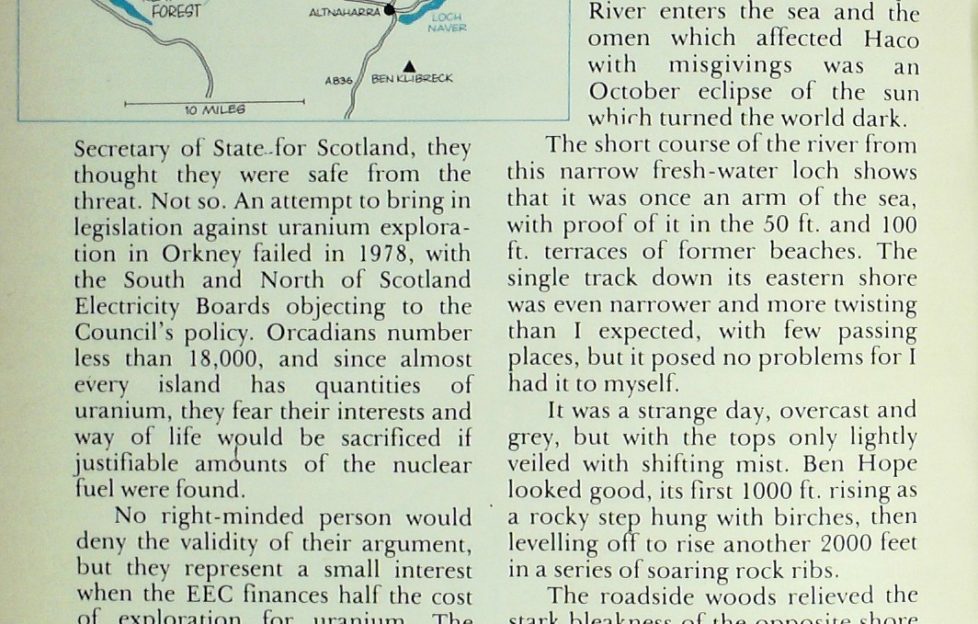

Back on the Mainland

No more than 48 hours later I stood overlooking the spot in Sutherland where King Haco anchored his fleet on Loch Eriboll and received an omen of ill before turning Cape Wrath on his fateful sail south.

The place was where the Hope River enters the sea and the omen which affected Haco with misgivings was an October eclipse of the sun which turned the world dark.

The short course of the river from this narrow fresh-water loch shows that it was once an arm of the sea, with proof of it in the 50 ft. and 100 ft. terraces of former beaches. The single track down its eastern shore was even narrower and more twisting than I expected, with few passing places, but it posed no problems for I had it to myself.

It was a strange day, overcast and grey, but with the tops only lightly veiled with shifting mist. Ben Hope looked good, its first 1,000 ft. rising as a rocky step hung with birches, then levelling off to rise another 2,000 feet in a series of soaring rock ribs.

The roadside woods relieved the stark bleakness of the opposite shore, which lacked character compared to the steepness of the escarpments running for miles on the Ben Hope side. I was looking out for the broch known as Dun Dornadilla above the broken swirl of the Strathmore River, and suddenly there it was.

It was hereabouts that the Sutherland bard Rob Donn Mackay was born in 1777. His famous song “In Praise of Glen Golly” came to my mind when I came to the rough track leading off to Gobernuisgach Lodge close to the foot of the glen of the song.

The first time I came here it was not along the road but across country from Ben Loyal. That was during the war, and I was on embarkation leave before being posted abroad.

Beginning at the base of Loch Loyal where I had left the Tongue mail bus, I’d shouldered my pack across country to an empty house on the edge of Loch an Dithreibh, a wild oval of water between Ben Hope and Ben Loyal.

Three days later, having climbed them both, I struck south-west for Gobernuisgach, steering by compass over the peaty trackless country deep in mist. I remember the relief when I hit the track and saw the meeting of the glens where the lodge is sited.

In my hand now was the stained and tattered Ordnance Survey map I used that day, on paper, price 1/6. Yes, there was the footpath climbing away westward over the jumbled hills of the Reay Forest, disappearing out of sight.

An Otherworldly View

I remembered vividly the moment of getting over the other side for the ferocity of the rainstorm which blew up. Crouched under my army gas cape I “cooried doon” expecting such a wild drumming to ease off before long.

The world was surely as black as the eclipse which presaged ill for King Haco but then came a sight I have never forgotten.

Out of the murk stood the point of Ben Stack, shadow rather than substance, mighty as the Matterhorn, and below it dozens of rocky mounds encradling saucer gleams of lochans.

It was a vision of Sutherland I have never had before or since. It didn’t seem to belong to this world and I had a sense of loss in the suddenness of its passing as the vapours dispersed and the mystery vanished.

I was thoroughly soaked as I bounded down the pass towards a house marked “Lone” on the map. The name suggested my mood. I was in need of company and decided to go on to Airdachuillan in the hope of a dry comfortable doss for I had no tent.

It was an inspirational move, for the Scobbie family gave me the kind of welcome you can never forget, not just good food and lodgings but laughter and fun.

In my few days with them I forgot I was a soldier as I climbed everything in sight, played ping-pong at night and heard a wheen of good stories from a sharp-shooter of the First World War.

A Wanted Man

Then came the time to catch the mail car to take me to the train at Lairg. In Glasgow I got a shock when I found I was a wanted man. My unit had been trying to recall me, and had put the police on my trail!

My mother was worried still but I spoke on the telephone to my adjutant and came home smiling.

The alarm had been called off and I was awarded two extra days to add to my 14 spent in the hills.

You can appreciate why I was in no hurry now to leave the Gobernuisgach track as I mused on these memories – and another one. The time when I returned here after the war with my pal Matt and returned to the Reay by walking through Glen Golly and over a pass into Strath Dionard.

We found the glen was all that Rob Donn had described, a place of enchantment. Later, with another companion, we were to make the last important routes to be done on the great cliffs of that lonely strath of greenshank and black-throated divers.

Regretfully now I got back into the car and swung away south for Altnaharra on Loch Naver where the sun was shining and Ben Klibreck shining olive-green above the spruce plantations. After the track I had been on, the road to Lairg and Invershin felt almost a highway, but the new experience awaiting me was the crossing over the Cromarty Firth bridge.

It was more than just curiosity to see the new bridge and the broad connecting road linking it that took me this way. It was by way of being a pilgrimage to see again the barn that the writer, Jane Duncan, converted into a home in her beloved Jemimaville, and to go to the nearby cemetery where she lies buried.

It had been my good fortune to meet the author and work as a photographer with her on an article for this magazine about the village. The piece was entitled “Postmark Poyntzfield” and she began it:

“In the Highlands there is a district called the Black Isle which is neither black nor an island, and in the Black Isle there is a village Post Office called Poyntzfield, which is not the name of a village.”

The article appeared in October 1965, and until my meeting with the writer, I had never looked at the Black Isle very carefully.

Some of the Best Agricultural Land in Scotland

Now here I was again outside the double-storied house with the name “Old Store” on the wrought-iron gate. In her autobiographical book Letter from Reachfar she turned the pages back to her early days in Dumbarton and abroad and then told how she came back here as a widow when she was beginning to make her mark as a writer.

The Black Isle could scarcely have looked better than it did on this recent visit, living up to Jane Duncan’s description of it as “an ordered land of comely farms which contain some of the best agricultural land in Scotland.”

I didn’t know how lucky I was with the weather until I crossed the Kessock Ferry and headed south, driving into heavy rain as I sped down the refurbished and fast A9 for Perth. Fatigue was setting in by Kincraig so I put in for the night.

The Spey valley is normally more bracing than the west, but it had a soporific quality following the rain as the morning sun dispersed the mist and brought out scents of heather and pines, putting a burnish on the grey rocks and a touch of blue on the gently winding Spey.

Loch Insh, reflecting gay-coloured fibre-glass canoes and the bright sails of dinghies, was just coming to recreational life as I took the back road which winds through the birches by Irish and Tromie Bridge to Ruthven Barracks. There are changes here as the new A9 is driven on a new line under the ruined barracks between it and the Spey; Newtonmore and Kingussie are now bypassed and these villages will revert to the peaceful places they used to be.

You can certainly make good time safely on Drumochter Pass now, by-passing Dalwhinnie and hardly noticing you are climbing, which means you have to take all the greater care when you come back on to the old blind crests and twists between Calvine and Killiecrankie.

A day is a long time in a motor car. I can’t stand it, so at Pitlochry I was glad to turn off and make a cross-country dash across to Newtyle and simmer down with friends in a farmhouse on the sunny slopes of the Sidlaws.

For farming this is a country that has everything—good hills for sheep and easy enough to shepherd them from a Land-Rover, big fields of barley, lush fields for cattle and orchards for fruit.

In an easy walk I could look across to the blue point of Schiehallion and sweep from Ben Lawers round to the Fife Lomonds, or across to Kirriemuir and the glens rising behind to the Grampians.

I chose to leave late and drive home to Gartocharn on Loch Lomondside in the light of a full moon. The roads were quiet and the huge bulk of Ben Lomond was hard black against the luminescent sky as I turned the key in the door. It was good to be away but I was glad to be back.

For me it had been a good summer. To be truthful, I can’t really remember a bad one, not in a country like ours that has so many places that are so different.

Read more from Tom next Friday

More…

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archives of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly but surely getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here.