Tom Weir | Jura In The Sun

Tom took a holiday in September 1975 to the Isle of Jura to catch the last of the summer sunshine and catch up with the crofters . . .

In the brilliance of the full moon it was no hardship rising at 2 a.m. and driving off for Jura to meet up with my sister Molly and her husband Sandy, who had rented a holiday cottage at Craighouse.

“We’ll meet you off the early ferry at Feolin. And tell Rhona to bring a hot-water bottle for herself—the nights are cold.”

Sure enough, there was a white glitter of frost on the grass verges as we climbed over the Rest and Be Thankful and wound round Loch Fyne to a sleeping Inveraray. The glory of the sunrise hit us at Tarbert, and I grabbed my camera at the sight of the glass-calm loch and its silhouetted fishing boats.

The early rise was worth it for that moment alone. All we had to do now was drive seven miles down the West Loch to Kennacraig, where the squat car ferry stood waiting to leave at six. As the time was not yet 5 a.m., we parked the car, went aboard, located a comfortable corner couch and stretched out. I didn’t even hear the ship leave port, but woke up as we arrived at Port Askaig.

The time was only 8 a.m. We were half an hour ahead of schedule, and a minibus stood at the jetty on the Jura shore.

“If you want a lift, step in— we can’t miss any car that’s coming to meet you.”

Glad cries of pleasure when we met our hosts only a mile or two from the house. Soon we were sitting down to a ham and egg breakfast and hearing about the marvellous peace and tranquillity of Jura in the sun.

Looking out of the window, I was reflecting that my first arrival on Jura nearly 20 years ago was as sudden as this one, in that I was there before I knew it. I had been invited by a Jura man to sail in a cabin cruiser from Largs, so our route had been through the Crinan Canal, reached by the Kyles of Bute, so it was in darkness on the second evening we were beating down the Sound of Jura.

Dan McKellar was the navigator, examining the charts and reading off our position from the flashing lights marking rocks and shore. The night was black, and we seemed to have been bumping down the choppy sound for a very long time. Dan was confident.

“Any man who can’t find his own house in Jura even in the dark is no sailor,” said he. And his steering was so faultless that when he switched on the searchlight on our deck its beam picked out the white square of his house.

Sorry to say, my old climbing friend Dan is dead now, and it was maybe because of that I hadn’t been back to Jura. It had been a great week there, and my chief memory of it was of social visiting and much laughter and Gaelic song.

Now I felt ready to come back and to renew old memories of the landscape. We set off first for the southern tip. I certainly didn’t expect to be remembered on Jura, but the very first native I met stood aside from the Highland cattle he was herding to shake hands and say it was a long time since I was there, adding, ” I still have the photo you sent me of the horses drinking at the burn !”

I asked him about the crofting.

“I’ve thirty cattle and some sheep, but I don’t do much cultivation now. Indeed, nobody is doing any. We’re all getting old. My brother died last year, and we lost another crofter recently, so you could say there are only five crofters left on Jura. Apart from some potatoes for the house and a very little oats, we’re growing nothing else.”

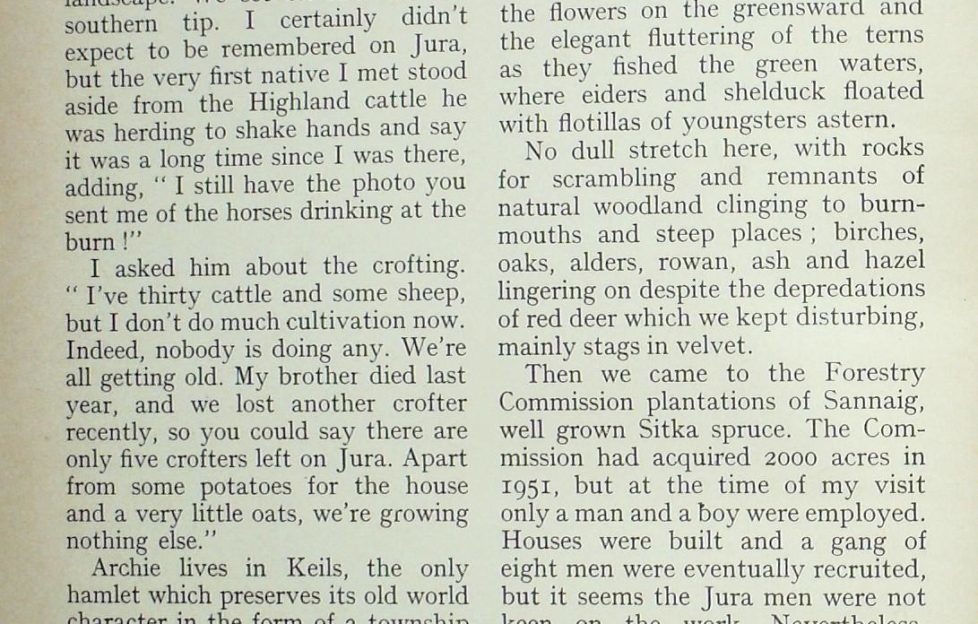

Archie lives in Keils, the only hamlet which preserves its old world character in the form of a township group with a few thatched houses.

“You’ll be coming up,” he said. “You know when I was young there were fifty living in Keils. Today there are only four.”

the long, broad wings gave an impression of sinister power

Walking to the new distillery block behind Craighouse pier, I learned that the new bungalows along the road had been built for incoming workers. Since the total labour force is only ten, plus manager and Exciseman, it had made little difference to employment among locals, though this was supposed to be part of its purpose in 1963 when the distillery was built. The initiative for it came from two of the four Jura landowners in company with Scottish and Newcastle Breweries, Ltd.

Molly and Sandy couldn’t understand why I had taken so long to come back to Jura. And I must admit the island seemed to be reproaching me by its brilliance that morning of shining sea as we took to the wild shore and followed the ups and downs of the craggy coast, enjoying the flowers on the greensward and the elegant fluttering of the terns as they fished the green waters, where eiders and shelduck floated with flotillas of youngsters astern.

No dull stretch here, with rocks for scrambling and remnants of natural woodland clinging to burn- mouths and steep places ; birches, oaks, alders, rowan, ash and hazel lingering on despite the depredations of red deer which we kept disturbing, mainly stags in velvet.

Then we came to the Forestry Commission plantations of Sannaig, well grown Sitka spruce. The Commission had acquired 2000 acres in 1951, but at the time of my visit only a man and a boy were employed. Houses were built and a gang of eight men were eventually recruited, but it seems the Jura men were not keen on the work. Nevertheless, some 1500 acres has been planted, here and on the Lagg-Tarbert coast. The Commission tells me that the remaining 500 acres will be planted over the next few years by forest workers based on Islay.

Nearing the attractive bays below Jura House there was a sudden squealing of alarm from lapwings, redshanks, curlews and crows as a huge tawny bird swept down at an angle, a sinister “bomber” being attacked by “fighters” as it was buzzed by the angry mob. In this low country the eagle looked even more massive than in a mountain setting as it beat across the greensward, the sun gleaming on its out-thrust golden head, the long, broad wings giving an impression of sinister power as we watched it swing away, still under attack.

“Imagine the cheek of these wee birds !” said Molly, flabbergasted.

Just ahead of us now was a rocky pancake of island called Fraoch Eilean with the ruins of a castle on it. The great Somerled built Claig Castle to guard the Sound of Islay. King of Argyll around the year 1130, he built a fleet of ships to fight the Norsemen, and the naval battle was fought off Islay’s west coast in 1156. His victory drove the Norse galleys from Kintyre and the Southern Hebrides.

Thereafter he ruled all the islands south of Ardnamurchan Point from Islay.

Just a little farther on and we moved from history to pre-history at the superbly sited standing stone of Ardfin. This 12-foot-high stone goes back 3000 years before Somerled, to the Bronze Age. Of the men who carried it here we know little. Strangely, it is in Jura that traces of the very first men in Scotland have been found—flint arrowheads uncovered in the sand dating back over 9000 years. Perhaps the proliferation of caves, large and small, made Jura a natural island for colonisation by the first shore-dwelling people looking for a place to settle.

The caves lie mostly in the north and west. Behind them stretches the largest extent of the most poverty- stricken bedrock in the Highlands, rising in peat desert and quartzite screes to over 2500 feet in the Paps, and falling east to a narrow coastal strip of relatively fertile schists indented with natural harbours. This is where the present half-dozen hamlets of the Jura folk are sited, within reach of 24 miles of coast road running from Feolin on the Sound of lslay to Ardlussa, the last settlement. The entire western desert is uninhabited.

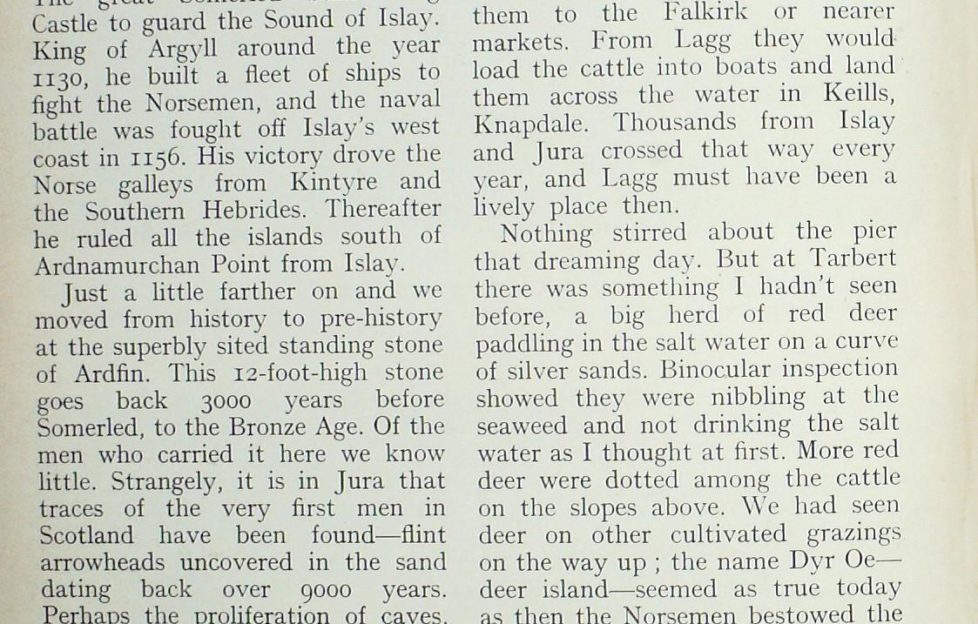

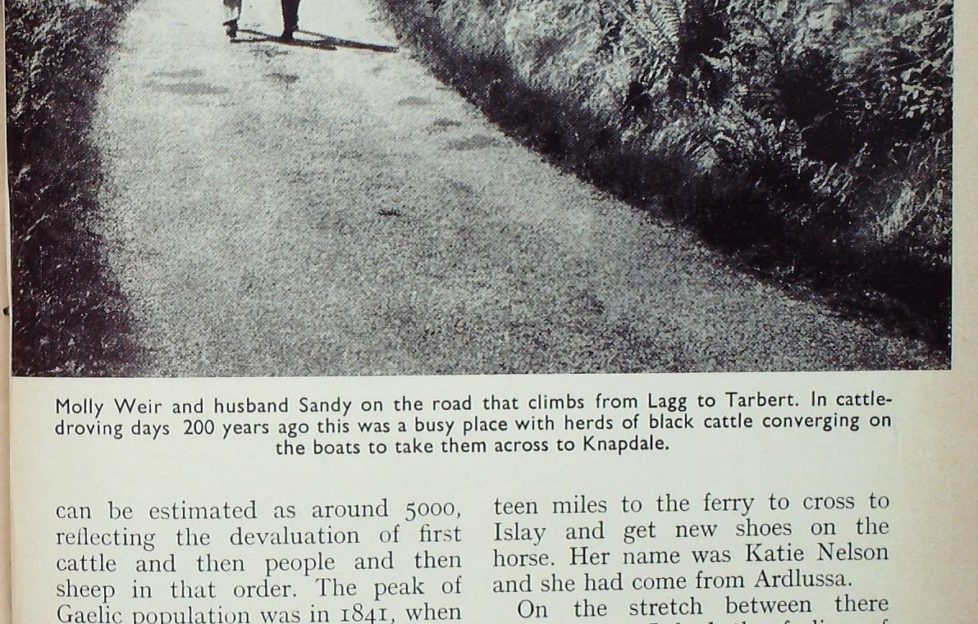

We went exploring north up there next day. The sun was warm again, yet visibility extended from distant Ben Cruachan to the Arran peaks. Following the road to Lagg, I tried to imagine Jura when its total economy was in small black cattle, and drovers would leave to walk them to the Falkirk or nearer markets. From Lagg they would load the cattle into boats and land them across the water in Keills, Knapdale. Thousands from Islay and Jura crossed that way every year, and Lagg must have been a lively place then.

The name Dyr Oe— deer island—seemed as true today as when the Norsemen bestowed the name upon it.

Nothing stirred about the pier that dreaming day. But at Tarbert there was something I hadn’t seen before, a big herd of red deer paddling in the salt water on a curve of silver sands. Binocular inspection showed they were nibbling at the seaweed and not drinking the salt water as I thought at first. More red deer were dotted among the cattle on the slopes above. We had seen deer on other cultivated grazings on the way up ; the name Dyr Oe— deer island—seemed as true today as when the Norsemen bestowed the name upon it.

No doubt the first cave men and the Vikings found a source of food in hunting the deer. But the subsequent Gaelic population who raised cattle and tended the fields held them in check, for in Martin Martin’s time, as reported in his classic Western Isles of Scotland (1695) he mentions the figure of 300 red deer grazing on the hills and “not to be hunted without the steward’s licence.”

Today the deer figures for Jura can be estimated as around 5000, reflecting the devaluation of first cattle and then people and then sheep in that order. The peak of Gaelic population was in 1841, when it stood at 1320, before rising rents forced them aboard emigrant ships or to seek a new life on the mainland. And with their going the red deer were waiting in the wings to take over from the sheep, whose hungry mouths had eaten the fertility out of the best ground.

Beyond Tarbert, along the road came jogging towards us a Highland pony with a slim figure on its bare back. Barefooted herself, the girl looked the picture of contentment as she told us she was riding seventeen miles to the ferry to cross to Islay and get new shoes on the horse. Her name was Katie Nelson and she had come from Ardlussa.

On the stretch between there and Tarbert I had the feeling of being in Sutherland, among lochs fringed with bog cotton, and summits grey with quartzite whose slopes were peat-blanket. What I’d not expected to find were skirling Arctic skuas cavorting in tern-like flight above a nesting flat. Beneath our feet were fly-catching plants, butterworts in blue flower, and red hairs of sundew baited with sticky moisture.

After this barrenness, Ardlussa seemed a fertile oasis of trees and singing birds, with a salmon river emptying into a fine bay. This was the place for a picnic, but first we had a paddle to cool off in the hot sun, then on the greensward scented with thyme we lay back and just enjoyed being there.

Originally we had intended to go on up a deteriorating track for nine miles to the lonely croft of Barnhill, where author George Orwell looked into the future as though with second sight and wrote 1984, a transposition of 1948 when he did his writing. Amazing that such a forward-looking vision of modern society should have been written in such a backward place, and frightening that it should be coming true today.

Orwell, in 1946, was critical of the four landowners of Jura and of the sporting economy to which he saw everything being sacrificed, including the crofters. Yet times have moved on here, too, and the facts of today are that few except the old want the crofting life. The able-bodied of today are looking for a modem standard of life which can be obtained only by a weekly wage packet. The truth of this can be tested anywhere in the Highlands and Islands, even in former strongholds of crofting like the Outer Hebrides.

During his West Highland Survey, at the time Orwell made his criticism, Frank Fraser Darling (now Sir Frank) found that the Jura crofts were better able to give a living than the smaller crofts in most of the Highlands. He saw the need, however, to cut down deer numbers if crofting was to enlarge further. But in summary he saw Jura as hopeless except as deer forest because of the large area of its 146 square miles which is acid ground.

However, there is nothing like talking to folk who are actually trying to win a living from the land, and next day on Knockrome I got the chance when I met a fresh-faced lady of vigour walking up the track. She told me her croft was 23 acres arable and 300 acres hill, but that you couldn’t get much of a living from it, not after you had paid the freight charges to get the beasts to market.

Knockrome is the most superbly sited crofting township on Jura, sitting high above the sweep of Small Isles Bay with a view to Craighouse and the Paps rising gracefully above. And just above the houses by a short climb, another vista, over the perfect horseshoe of Lowlandman’s Bay to the north coast.

It is customary to think of Islay as Queen of the Hebrides for its fertility, fine farms and general prosperity, and Jura across the sound with its peat and rock desert and scanty population as the joker. This is a modern view. Martin Martin thought differently. This is what he wrote 280 years ago :

This isle is perhaps the wholesomest plot of ground either in the Isles or Continent of Scotland, as appears by the long life of the natives and their state of health, to which the height of the hills is believed to contribute in large measure, by the fresh breeze of wind that come from them to purify the air ; whereas Islay and Gigha, on each side this isle, are much lower, and are not so wholesome by far, being liable to several diseases that are not here. The inhabitants observe that the air of this place is perfectly pure, from the middle of March till the end or middle of September.

Several of the natives have lived to a great age. I was told that one of them, called Gillouir MacCrain, lived to have kept one hundred and eighty Christmases in his own house. He died about fifty years ago, and there are several of his acquaintances living to this day, from whom I had this account.

Alas, Jura has had a sad year for deaths amongst its grand old folk, no fewer than eighteen, which is a very big loss in a community now numbering well below 200. The children were playing outside the fine new school as we passed, and I had a word with the head teacher.

“This is only my second year here,” she told me. “I came from England to Jura, but I love it here; the children are so nice and it is such a beautiful place, away from the rat-race.”

We would have liked to accept her invitation to visit the school, but time was running out since we were due off on the ferry that evening.

Molly and Sandy still had a week, during which the sun shone almost non-stop, and they walked and bathed in delectable coves where they had the sands to themselves without another human being in sight. And as they enthused to me afterwards about the island, I thought I could see the sun-tanned face of my old friend Dan McKellar, his gold tooth showing in an “I told you so” smile ; Jura was always the perfect place in the world for him. Often enough Dan talked to me about giving up his work in Glasgow as a manager and retiring to his cottage perched above Small Isles Bay. Tragically, he died in an accident, but maybe his Tir nan Og is not so unlike Jura.

For more of Tom’s columns check back here every Friday.