Tom Weir | The Shetland Way

The oil, the seabirds, and the joining of Norse and Scots heritage…

Here, indeed, was wonderful luck — a spring-like morning of soft sunshine and we were booked in a slow-flying Loganair Islander to take off from Sumburgh at the southern tip of the Shetlands and fly the whole length of the hundred islands whose ultimate points, Muckle Flugga and the Out Stack, are in the same latitude as South Greenland.

What a surprise it was to see the mammoth size of the £10 million airport compared to the tiny strip I last saw twelve years ago! Planes and helicopters of all sizes were buzzing about in a constant landing and taking off, for Sumburgh is the aerial hub of Britain’s North Sea Oil industry and shortly it will have its own special terminal to deal with this activity serving the rigs.

The airfield occupies what seems a tiny neck of land between the “tail fins” of Shetland on which perches Sumburgh Head Lighthouse, and the approach on a big passenger aircraft is exciting as the plane almost grazes the cliff face.

A subtlety of colours…

Taking off in the slow-flying Islander, I could appreciate it even more, seen in relation to the thin spine of mainland stretching ahead, and out on the southern horizon the dark shape of Fair Isle to the south.

A subtlety of colours passed below us : the browns of moors, hard greys of seacliffs, the white of bursting waves echoed by a dusting of snow on the whaleback summits, the green cirques of cultivation dotted with the squares of clustering croft houses, and below them wee, natural harbours with white boats drawn up.

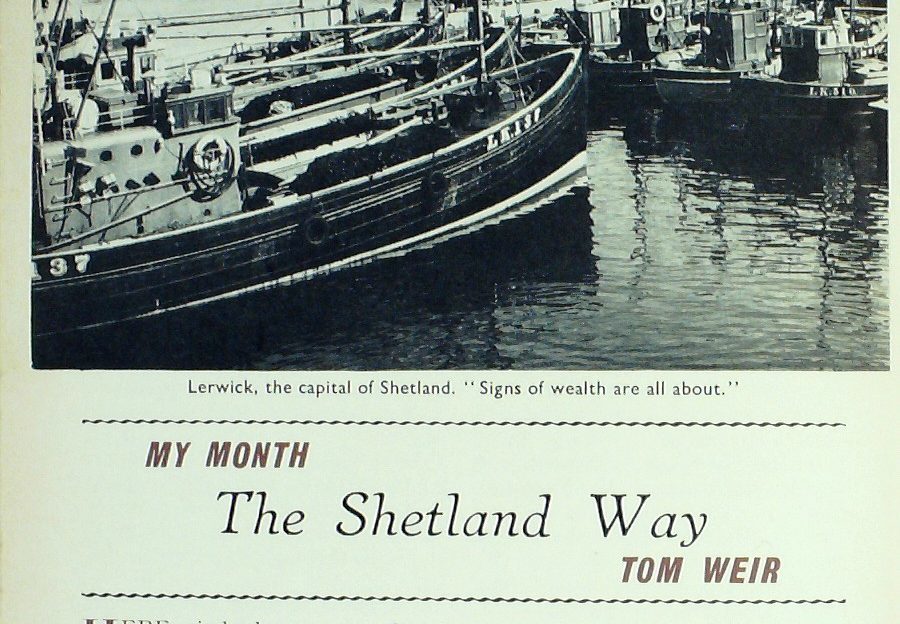

A tilt of the wing over Sandwick and we were skimming its neighbouring isle, Mousa, for a look at its broch, the best preserved of all these mysterious structures built as defence points in pre-Norse times against unknown enemies. Wigeon duck rose with a flash of white wings and Shetland sheep raced over hill-sides divided with stone walls and peppered with the ruins of a vanished people. On we flew for Bressay Sound to curl over the only town in the Shetlands, Lerwick, built on a steep-faced peninsula above a great natural harbour much extended since I was last here. What had been green shore to the north is now a great oil service base, with a constant coming and going of oil-rig ships, while on the hillside above it was a vast armoury of pipes and other equipment.

The most striking thing about the town itself was the number of new housing schemes, the result of the big expansion of population due to its new industrial importance. Former shops in Commercial Street are now offices, and the congestion of traffic has caused the shops to move north where there is space for parking. Signs of wealth are all about. In figures, harbour revenues which were £400,000 in pre-oil days, amount now to around £1.5 million. Are the people happier for it? This is what I wanted to discover.

Curving over rural Bressay, served by car ferry every hour from Lerwick, we headed north into the land and seascape of the voes, the big inlets which segment the coast. Opposite the broad inlet of Dury Voe I looked down on Whalsay, well named the “Bonny Isle”. It looked green and prosperous—as I knew it was, for its fields and harbours support about a thousand people.

Fishing is the mainstay here, and at Symbister School men can study for a skippers’ ticket if they feel inclined. Just beyond to the east was the cluster of rocks called the Out Skerries, rocks which support another enterprising fishing community. By contrast 1 could see to the west the crowding timber squares of the Toft work-camp which houses many of the Sullom Voe workers.

The flight line now was up the east coast of Yell, peatiest of the Shetlands, with a population of over 1000 living on an island 17 miles long by seven miles broad, largest of the North Isles. Our flight line gave us a fine view of the crofting townships, and colourfully attractive they looked, lit by shafts of sun and rainbows in a sprinkle of showers.

To the Meeting Place of the Oceans

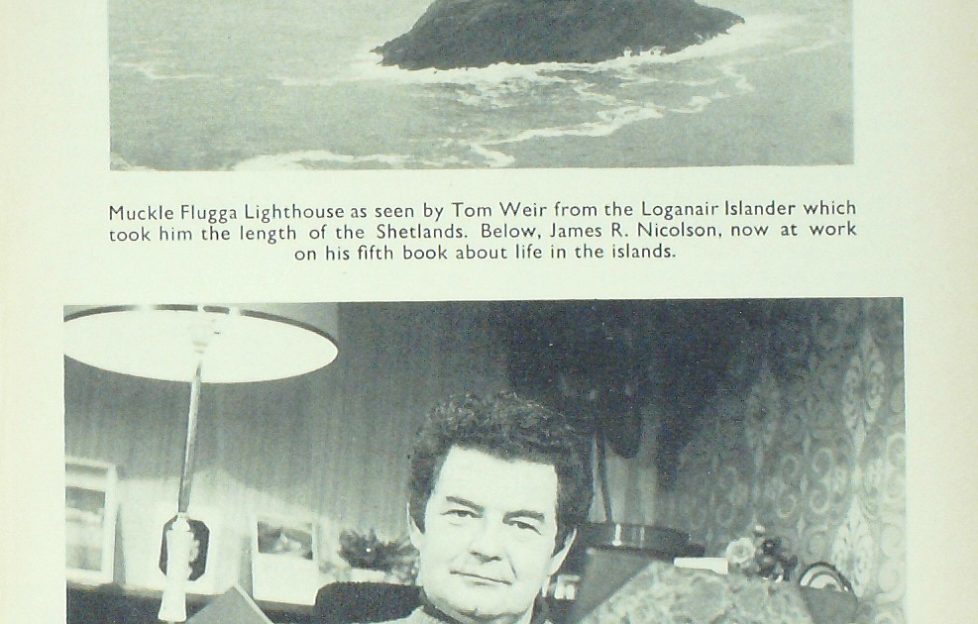

Only one more island to go now— Unst, and it was a thrill to look down on the Loch of Cliff, the most northerly sheet of fresh water in Scotland, three miles in length and with evidence around its shores that trees grew here around 500 B.C. Only a narrow neck separates this slit of loch from the sea inlet of the Burra Firth, and flying low over it for three miles we were waiting for the moment of turning its headland. Suddenly it was there, Muckle Flugga Lighthouse, perched on a grey ridge of rock, and beyond it the pancake of the Out Stack- Ultima Thule—edge of the world indeed.

The pilot swung round in a great arc to let us savour this meeting place of the oceans—the Atlantic, North Sea and the Arctic ahead, and behind us the cliffs of Henna Ness rearing up 600 feet. Countless birds flew out in alarm, mostly fulmars and shags and gulls, and a few gannets.

We felt like birds ourselves as our wings tilted steeply into the cliff to follow the line of a gully and climb sensationally to 1,000 feet over the perched cupolas of the Royal Air Force early warning station which is part of the NATO defence system.

The population of Unst is about the same as that of Yell, and the way the clouds were behaving it was impossible to separate one island from the other as we flew straight towards the vast yellow blob which was the out-of-focus sun magnified hugely by a curtain of rain. Racing over a peat-dark land spattered with innumerable lochs, each a winking eye of reflected light, was a strange other-worldly experience akin perhaps to looking down on another planet.

Down by Yell Sound I recognised the beach where, earlier, I had been slithering about on boulders black with oil and looking with apprehension at another slick out on the water. With me was Bobby Tulloch, who had advertised for helpers to search for dead and dying birds along 10 miles of coast contaminated by the spillage from Sullom Voe.

The Cost of Oil

Bobby works for the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds as their Shetland representative, and we have been friends for many a year now. He was furious at what had happened.

“Tell people about this mess,” he said to me. “Explain to them that there is no known way of clearing it up. It has wiped out the duck and diver population of Yell Sound. Look at this great northern diver, one of over a hundred dead we’ve found, the biggest kill of these rare birds in history. Twenty otters who use this bit of shore have had a miserable death. The tysties and eiders who live here have been almost wiped out, so have long-tailed ducks and scoters. I could tell you of the 3,000 birds we’ve picked up as black as if they had been dipped in treacle.

“Look at these sheep. See the oil matting their wool? They come to the beach to eat seaweed, and when they get the oil inside their stomachs they die. The death rate is bound to be high. The Shetlanders are furious at the inadequacy of the preparations to deal with this accident. Now we’ll find out the true cost of North Sea oil, for this is only a small spill of 1,100 tons. What will a big one be like?”

Sullom Voe lies across Yell Sound, and in a few moments’ air-time we were there, and I was having mv first view of the largest oil terminal in Europe, with storage tanks to receive the black gold by pipeline from fields over 100 miles out under the North Sea. The first tanker took its first cargo out on November 30 last year, and it was the twelfth which spilled its oil.

Prepared in mind as I was for something gigantic, I was staggered at the sheer size of the development on a thousand-acre site which, although operational, is far from complete. I now appreciated the statistic that just one oil tank would supply enough petrol to take a family car to the moon and back 25 times. Sullom Voe is a “common user” plant, with 30 companies having an interest in the processing and export of oil and liquid gas from the North Sea fields, to build it has been an army-type operation involving massive excavations and big shipping movements in difficult seas to bring the materials to keep thousands of men employed.

In 23 days on Shetland I was to talk to plenty of oil workers and hear the views of many clear-thinking Shetlanders on the impact of oil on their way of life. Meantime, I was concentrating on the topography, with out there to the west the snowy hogback of Ronas Hill at 1475 the highest in the Shetlands, and beyond it, out on the horizon, the triple crown of Foula, remotest inhabited island in Britain and stiil holding on to its tiny population.

Now for Scalloway and all the narrow slits of voes between Whiteness and the islands of Trondra and Burra. Across Gift Sound at Dunrossness the scenery became exciting, with St Ninian’s isle and the Loch of Spiggie backed by the great cliffs of Fitful Head—some of the loveliest country in all Shetland.

The airfield was just round the corner, but between us and it was Jarlshof, one of the most important archaeological sites ever discovered, containing as it does, on a single three-acre site at the sea edge, a whole chronology in stone, covering a period of 1500 years from people who lived a Stone Age way of subsistence to the builders of the brochs and the colonisation of the Vikings. It was their invention of the Long Ship, a real breakthrough in technology, which enabled the Norsemen to win their way from Norway to Orkney, Shetland, the Hebrides, Faroe, Iceland, Greenland and eventually America. Here at Jarlshof are the foundations of the most complete Norse farming site found in Britain, though a recent find of a similar foundation in Unst may prove its equal.

The People of Shetland

In Scalloway, I found myself at the house of Shetland author James K. Nicolson, author of four definitive books on the islands, his latest being Traditional Life in Shetland, which is well researched and beautifully written. He was busy on a fifth when I called, sheaves of paper round his armchair and a big ledger of one of the famous trading companies on his knee from which he was gleaning information.

Strong, broad and in his prime, the eyes below the black curly hair had a humorous twinkle as he settled down in his living-room while two of his four children played with their toys.

The son of a crofter-fisherman, and a graduate of Aberdeen University, he holds a combined M.A.,B.Sc. degree. He handed me a thin red book saying, “That’s one of my books which very few people have ever seen. It didn’t make me or the publisher any money. It was my first, and I wrote it when I was working as a geologist in Sierra Leone in West Africa. I like it because it’s about that country, which I enjoyed and I just had to write it.

“The Shetlanders are great readers, and seem to be very aware of their historical roots. A lot of people feel afraid of what oil has done to Shetland, because crofters and former fishermen commute fair distances to Sullom Voe. Mothers who stayed at home now go out and earn relatively big money making beds or working in the canteens. Local schools have filled up with children from outside. New roads and ferries make it possible to get quickly from Unst to Lerwick.

“Before I took to full-time writing I had started work in the oil industry with a firm of consulting engineers in Shetland. There is no doubt at all in my mind that we needed an additional industry here if we were to keep our population. It’s true that the fishing, knitwear trade and crofting were doing well and that Shetland didn’t really need the oil industry when it came. But we were finely balanced, vulnerable. Look what’s happened to the fishing. Iceland and Faroe have extended their limits, so the foreign boats come here and are cleaning up our waters. Catches are down drastically.

“The oil industry gave a sudden opportunity for Shetland brains to come back to Shetland, and the islanders have come flooding home. Never mind the 6,000 and more incomers at the camps. The Shetland population is now up from 17,000 to over 21,000, the highest for 40 years, and that can only be a good thing for the future of these islands.

“There’s vigour and vitality— inflation, too—but the important thing is that there’s money coming into the Shetland kitty from that oil, which will be used to build up the old industries and create new opportunities when the oil has gone. There are bad side effects—a rise in crime, more death on the roads (usually due to drink). Youngsters have got too much money. But look at Lerwick’s Up Helly Aa, when 800 guisers with blazing torches march the streets. The whole thing is perfectly disciplined with never an accident. Thousands are out in the street to watch. Dances go on right through the night until the following morning, and there is never any damage or hooliganism. That’s the kind of folk we have in Shetland.”

The Fire Festival, First-hand

Well, I had the pleasure of fulfilling a lifetime’s ambition by being present at the 1979 Fire Festival, and the reality of it all went far beyond my hopes on that great night when the guiser Jarl, another Jim Nicolson, sailed his dragon ship through a waving double row of flaming torches held aloft by 794 guisers.

What made it all the more impressive was the sense of occasion— waiting for it in the darkness of a windy, bitter night and seeing shadowy’ forms passing to the mustering place to draw their heavy paraffin-impregnated torches and be marshalled into position with military precision. There they awaited the splendidly attired guiser Jarl’s squad and the galley to pass up their ranks.

Down in the crowd we lined the route, waiting for the explosive bang of a lifeboat maroon, the signal for torches to burst into red flame like struck matches. Then the whole splendid sight was revealed: the vivid colours of the exotic dragon ship, the Jarl mounted aloft, and his crew marching alongside, their breastplates and horned helmets gleaming in the fire glow, the brass band playing and the roar of the Up Helly Aa song sounding from the counter-marchers like a mighty fragment of opera, with the galley in a maze of torches.

In mere words one cannot capture the emotional dimension of the blend of sound and colour and spectacle behind the whole experience: the guisers in their weird masks and comical outfits contrasting with the Jarl’s squad in their garb of cloaks, horned helmets, tunics, armoured breastplates and gartered legs. Now I knew why Jarls of other years used to tell me of having tears in their eyes at the climax of the ceremony.

That night Jim Nicolson was Egil Skallagrimsson, an Icelandic hero of the 9th century. There he was, his feathered helmet against the flames above his galley. And as he stood tall, more and more torches were forming the circle round the galley. Then sounded an explosion like a cannon shot—the maroon signal for the singing of the Galley Song, and out it thundered.

As the night air echoed with the splendid song, the guiser Jarl’s squad circled the galley raising their battle-axes to cheer the galley-builders and the torchmakers with a specially loud shout to honour the most important person in the event, the principal actor, Jarl Jim Nicolson, who climbed down amongst them from his ship as a rousing fanfare was played.

And as the last note died away, wave after wave of blazing torches were hurled at the dragon ship to send it leaping into flame with sparks flying and a great crackling. The beautiful ship that had taken months of spare-time work to build and ornament was beginning to sag in less than five minutes, and the open mouth of the dragon seemed to nod sagely before it fell to be consumed in the flames.

As it fiercely burned, the last song was sung, The Norseman’s Home:

The Norseman’s home in days gone by

Was on the rolling sea,

And there his pennon did defy

The foe of Normandy.

Then let us ne’er forget the rare,

Who bravely fought and died,

Who never filled a craven’s grave,

But ruled the foaming tide.

The noble spirits bold and free.

Too narrow was their land,

They roved the vide expansive sea,

And quelled the Xornian band.

Then let us all in harmony

Give honour to the brave,

The noble hardy, northern men

Who ruled the stormy wave.

The words hearken back to a far remembered time before the annexation of Shetland by Scotland and the gradual decline in status from freeman to oppressed tenant following 1471. It was this colonisation which caused the ancient Norn language of Norway to die out to become in time the rich Shetland dialect we know today.

Perhaps this explains the determination of the Shetlanders to go it alone with the oil companies and extract from them a profit from every barrel and a fair rent from every structure built on their ground, not for the sake of cash alone but to finance survival of the old way of life when the oil men pack up and go. I had plenty of opportunity to talk with a wide variety of people on every aspect of Shetland life, but all that will have to wait until next month.

You can read Tom Weir’s next update, Shetland Folk, next Friday!

More…

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archives of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly but surely getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here.