Richard Henry Brunton

A-Z Of Great Scots

« Previous Post- Agnes Randolf

- Richard Henry Brunton

- Christian Fletcher

- Helen Duncan

- Ebenezer MacRae

Richard Henry Brunton brought a mix of lighthouses, lifeboats and railways to Japan

Richard Henry Brunton brought a mix of lighthouses, lifeboats and railways to Japan

IN 1868, Japan’s waters were a risky place. The few lighthouses were very beautiful, like miniature temples, but short and frankly useless.

Sir Harry Parkes, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary for Britain in Japan, pressed the Japanese to act. Trade with the west was increasing and a number of ships had run aground.

The government called on the renowned Stevenson brothers. Did David and Thomas send their best lighthouse engineer on this prestigious mission? No. They chose someone with no experience of lighthouses.

Richard Henry Brunton was a 26-year-old railway engineer. The Stevensons thought his temperament and expertise made him perfect for the job.

They gave him a crash course in lighthouse engineering at their Edinburgh HQ before he set sail for Japan in June, 1868, with his wife, baby daughter and two assistants.

Scots in Japan

Arriving in August, Richard got to work as one of the new Meiji government’s first oyatoi gaikokujin, or foreign advisors. After charting the waters surrounding Japan, he chose sites for his lighthouses and set about building them in the Stevenson style.

There were virtually no masons, bricklayers or blacksmiths in Japan; they had to be trained before work could start. The country was in a time of upheaval, and his workmen were wary of this foreigner. They ignored his orders and got drunk on the job.

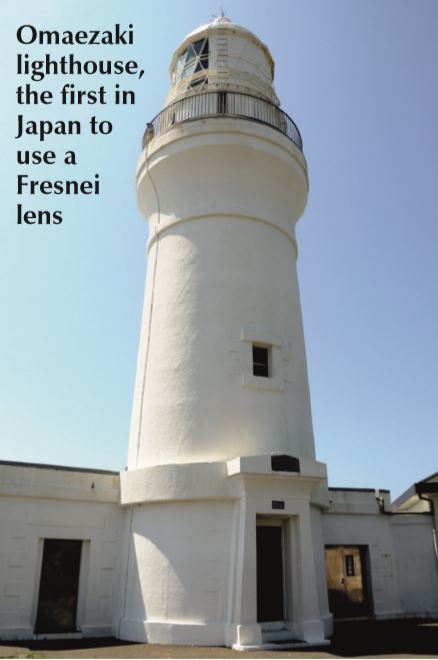

Eventually Richard sent for a team of Scottish engineers. Work progressed slowly, and by 1876, Richard had designed and built 26 lighthouses, which the Japanese still refer to as his “children”.

Credit: istock

Many are still in operation today. He created and trained a network of lighthouse keepers based on Scotland’s Northern Lighthouse Board, and set up a lifeboat service.

During his time in Japan, Richard also planned Yokohama’s sewage system, paved its streets and installed the city’s first gas lights.

He built telegraph lines and railway tracks between Japan’s major cities, and founded the country’s first civil engineering school. Not bad for seven-and-a-half years’ work.

In recognition, he was granted an audience with Emperor Meiji, and squeezed in a final job before his return to Scotland: compiling the first Ordnance Survey map of Japan.

Discover more about the remarkable men and women who shaped Scotland and changed the world with our new bookazine Scottish Heroes

Available for online purchase from DC Thomson Shop or in stores at WHSmith