Ebenezer MacRae

A-Z Of Great Scots

« Previous Post- Richard Henry Brunton

- Christian Fletcher

- Helen Duncan

- Ebenezer MacRae

- Marjory Fleming

- Sir Alexander Glen

- Wyndham Halswelle

Ebenezer MacRae transformed the living conditions of Edinburgh’s working class

Ebenezer MacRae transformed the living conditions of Edinburgh’s working class

DURING the interwar years, one man was responsible for preserving Edinburgh’s cherished architectural history while also bringing the city into the modern world by creating social housing developments and public amenities like libraries and schools.

Though his forename, thanks to Charles Dickens, has become shorthand for a miserly misanthrope, during his two decades as City Architect, Ebenezer MacRae embodied the original meaning of his name – “stone of help”. One stone at a time, he helped build a liveable, workable Edinburgh that didn’t lose an ounce of its beauty, and his legacy can still be seen in the city today.

His legacy

Ebenezer trained as an architect before serving in the Royal Engineers during the First World War. After being appointed City Architect in 1925, and then Director of Housing the following year, his mission was to create council housing that would benefit the city’s working classes by being inexpensive, clean, well-lit and spacious.

The council wasn’t at all sure about this plan – they preferred the idea of subsidising private rentals – but Ebenezer wouldn’t budge. His perseverance paid off, and though he had many financial obstacles in his way, new housing sprang up at a startling rate throughout the city.

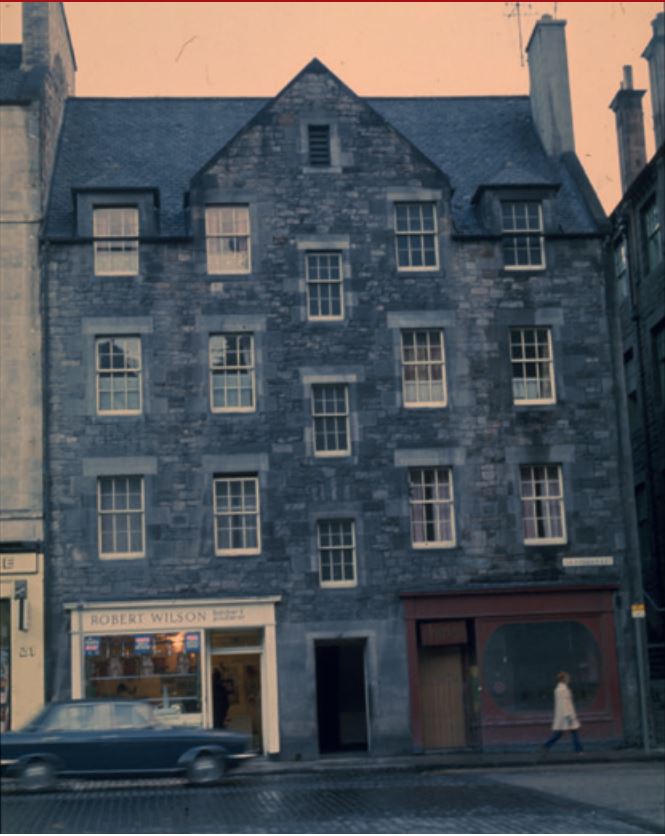

He championed the humble tenement as affordable housing close to people’s workplaces, in order to help them cut their travel costs. It took a brave man to propose erecting new tenements in the historic Old Town, but his infill developments were impressively sympathetic to the traditional architecture.

His secret? He refused to use concrete blocks, fighting for stone and rendered brick facades instead. He also painstakingly restored existing buildings, including a revamp of the Canongate’s 17th and 18th century tenements.

MacRae restored this building in Grassmarket in 1929

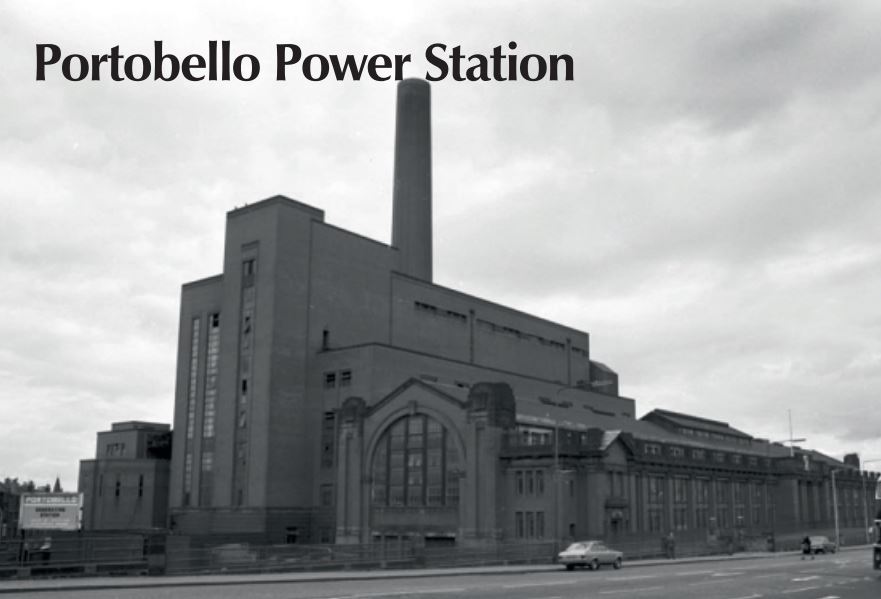

The suburbs also benefited from Ebenezer’s vision and the housing department built 12,000 new homes during his 21 years as City Architect. In addition to building tenements, housing estates, and dozens of public buildings, Ebenezer’s magnum opus was the redesign and extension of the mighty Portobello Power Station. The station supplied Edinburgh’s electricity for more than 50 years, its chimney looming over the rooftops until the late 1970s.

He was also very keen on street furniture, installing tram shelters, traffic lights and street lamps across the city, as well as designing its iconic blue police boxes. But Ebenezer knew that a modern capital city couldn’t survive by simply being a monument to its architectural past. He not only expanded Edinburgh, but vastly improved the lives of the ordinary people who called it home.

Discover more about the remarkable men and women who shaped Scotland and changed the world with our new bookazine Scottish Heroes

Available for online purchase from DC Thomson Shop or in stores at WHSmith