Tom Weir | On Top Of The Bass

A visit to the Bass Rock for Tom Weir was full of the tales of witches and escaped prisoners – and, of course, the cries of gannets…

To make a landing on the Bass Rock you need good luck. We didn’t get it on our first attempt. It had seemed that all was in our favour; a bedevilling sea mist had lifted before a light wind, and Skipper Fred Marr was ready at 9.30 a.m. to slip out of North Berwick’s tidal harbour.

Then disaster! A fishing boat coming in from the sea grounded on the bottom and blocked the entrance until the outgoing tide turned in the afternoon and floated it off.

In his long experience of sailing out of North Berwick Harbour, Fred had never seen such a thing happen before. However, he accepted his loss of income philosophically and waved me good-bye as I made off round the corner to the museum. There I learned a lot of things about the old town from the member of the staff who showed me round.

The North Berwick Witches

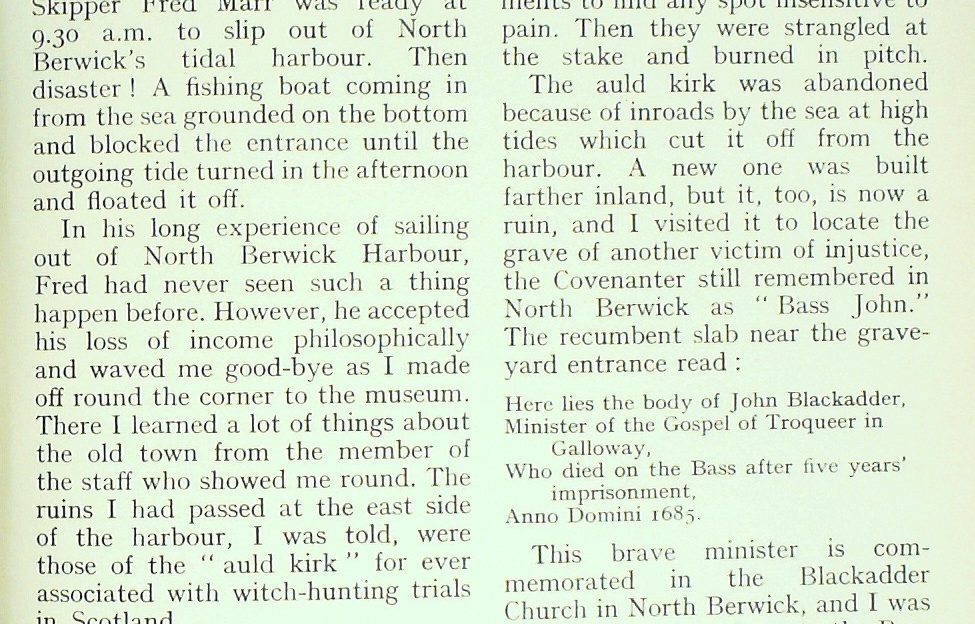

The ruins I had passed at the east side of the harbour, I was told, were those of the “auld kirk” forever associated with witch-hunting trials in Scotland.

James VI began the epidemic when he learned that a coven of witches had carried out devilish practices round the auld kirk of North Berwick, summoning up a storm at sea to wreck the ship carrying him and his bride from Denmark to Scotland. Confessions were wrung from the “witches” under torture with thumbscrews and breaking irons. Their naked skins were pricked with sharp instruments to find any spot insensitive to pain. Then they were strangled at the stake and burned in pitch.

The auld kirk was abandoned because of inroads by the sea at high tides which cut it off from the harbour. A new one was built farther inland, but it, too, is now a ruin, and I visited it to locate the grave of another victim of injustice, the Covenanter still remembered in North Berwick as “Bass John.” The recumbent slab near the graveyard entrance read :

Here lies the body of John Blackadder, Minister of the Gospel of Troqueer in Galloway,

Who died on the Bass after five years’ imprisonment,

Anno Domini 1685.

This brave minister is commemorated in the Blackadder Church in North Berwick, and I was all the keener now to go to the Bass and see his prison. But first I climbed Berwick Law, the 612-ft. hill whose building stone provided the walls of the old town. The path goes by the quarry, now a refuse dump, and the grassy zig-zagging path takes you up steeply to the jawbones of a whale which make a pointed arch just below the rocky summit.

It was good to see so many holiday visitors enjoying the pointed top on an afternoon which had become brilliant, with the sun on the harvest fields and the curving sands fringing the glittering sea.

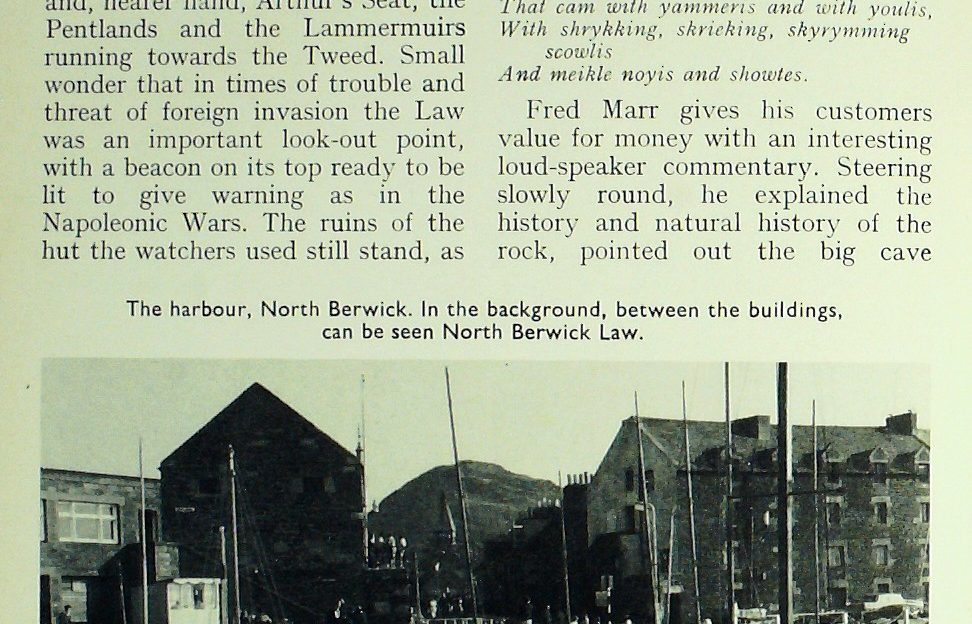

The Firth of Forth has great character, with its rocky islets, Fidra, the Lamb, Craigleith, the white hump of the Bass, and away beyond it, close to Fife, the battleship shape of the Isle of May.

And you appreciate from here that the Lowlands are by no means low, as your eye sweeps across the volcanic escarpments of the Ochils, the twin points of the Fife Lomonds, and, nearer hand, Arthur’s Seat, the Pentlands and the Lammermuirs running towards the Tweed. Small wonder that in times of trouble and threat of foreign invasion the Law was an important look-out point, with a beacon on its top ready to be lit to give warning as in the Napoleonic Wars. The ruins of the hut the watchers used still stand, as do the whale bones, though they are not the original jawbones erected in 1709. The present ones are replacements put there in 1936.

On to the Bass itself…

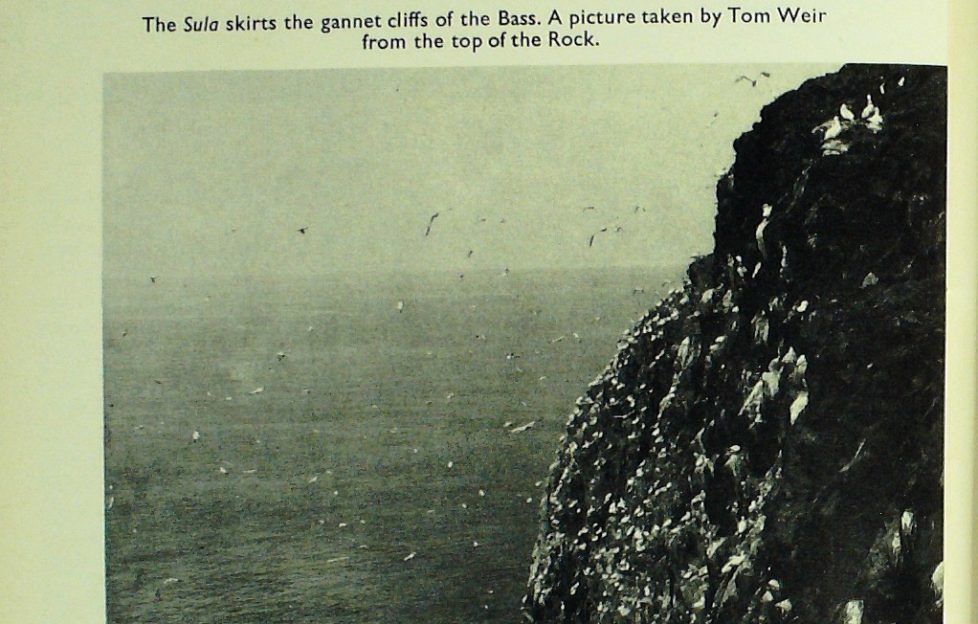

Yes, a very enjoyable day, which made the Bass Rock even more interesting for me next morning when, within half an hour of leaving the harbour we were bobbing under the big cliffs with a veritable blizzard of gannets’ wings above us.

It was as the poet Dunbar described it over 400 years ago :

The air was dirk it with fowlis That cam with yammeris and with youlis, With shrykking, shrieking, skyrymming scowlis

And meikle noyis and showtes.

Fred Marr gives his customers value for money with an interesting loud-speaker commentary. Steering slowly round, he explained the history and natural history of the rock, pointed out the big cave below the lighthouse which pierces right through the rock so that one can walk right through at low tide. And he was just getting on to the story of how the big garrison was conquered by a handful of Jacobites when the moment came for me to hop ashore on the slippery landing step of the stairway that climbs to the top of the rock.

This landing is the only weak point in the girdle of rocks that rings the Bass, and by building a fortress across it those who held it had an impregnable position. The lighthouse occupies the site of the former governor’s house, and to reach it you have to go through the thick-walled prison which once held over 40 prisoners, mostly men of the cloth, including John Blackadder.

Unluckily, John died just as he was about to be released. But retribution came to his captors only six years later when the prison held four young Jacobite officers captured at Cromdale in 1690. The story is that the whole garrison force was down working at the jetty except their immediate guard, and by a neat action they managed to shut them out of the fortress and threaten the enemy with their own guns.

It was not to be a temporary takeover ; they held out for three years against all the might of King William III. They flew the Scottish Lion for King James VII, and they were able to hold out with the help of two French Government boats which kept them victualed. They even increased their fighting strength from four to sixteen, and in the end negotiated an honourable peace settlement.

It is said that they laid on a banquet for the talks, bringing out their best food and wine to give the impression they had plenty, though, in fact, they were at their last gasp. The bluff worked. Small wonder the fortifications were dismantled shortly afterwards and the guns removed.

Today the only permanent inhabitants are the lighthouse- keepers who enjoy everything about the Bass except the overpowering smell of the increasing gannet colony which creeps ever closer to them.

“There’s more of them every year, and the whirling beam of the light doesn’t seem to bother them,” one of them told me.

Isle of the Gannets

The Bass Rock gannet colony is one of the oldest and best documented in Britain. Even the Latin name of the bird, Sula bassana, comes from the Bass, and until the 18th century the birds were harvested and sold in Edinburgh “all lawful days of the week, wind and weather serving.” Not only were the birds good eating, but their thick plumage was esteemed for feather beds, and their fat valued for waterproofing boots and as a medicine.

The more prosperous times of the 19th century saw an easing of exploitation by man at all gannet colonies. Even the St Kildans stopped raiding their stacks. Thus began the great population explosion. In 1902 the number of gannets in eight colonies was estimated at 50,000 pairs. Today the estimate is 142,000 in about a score of colonies. On the Bass, where numbers have more than doubled, gannets spend most of the year on the rock guarding their nesting places. They don’t leave until November, and begin arriving back again in December.

Not far above the lighthouse on the grassy upper part of the Bass is a tiny drystane chapel choked with the tall plant known as the Bass mallow. It was built to the memory of St Baldred, who had a retreat on the rock in the 8th century, probably in a beehive cell. The chapel was erected 800 years after his death. During the incarceration of Bass John the chapel was used as an ammunition store.

Gloomy as imprisonment in the cells must have been, the spirits of the prisoners must have risen when they were allowed out in pairs to exercise on the seven acres of greenery forming the apex of the 340-ft. rock. The sheep feeding there are said to have excelled in the quality of their mutton, but today the gannets are over-spilling from the crag on to the pasture, where they sit row upon row like articles in a shop window.

Even in autumn there were still quite a few downy-white chicks, though most were at the grey guga stage, wing-flapping restively and ready to tumble off the rock at the end of a long-drawn nesting process. It begins with 40 days inside the egg, then three months on a ledge of the Bass before the launch-out on unsteady wings to crash down on the sea and not be able to rise again until they have slimmed off their surplus weight. Then they have to learn to fly and crash-dive from heights to catch fish, though it will be years before they establish themselves as breeders on one of the few gannet rocks of which Scotland has the world monopoly.

Sitting on top of the Bass, I could see Fred Marr’s Sula coming round to the landing. As I hurried to meet him, I found it hard to believe I had been seven hours ashore.

Along the coast

Once you get a taste of the East Lothian coast you don’t feel like leaving until you have seen some more, and the bit I had in my mind to explore was that scenic backwater lying north of the road between Cockburnspath and Coldingham, where the gentle Lammermuirs plunge sensationally into the sea in cliffs over 500 feet high on a wild coast hardly touched by even minor roads.

The beginning itself is unusual when you take the track from Cockburnspath to Cove, and find a tunnel carved through the soft sandstone taking you to the neat harbour; round the corner is the caravan city of Pease Bay, occupying one of the few perfect curves of sand in Berwickshire. Better things lie two miles farther east at Redheugh, where the glowing sandstone suddenly changes to hard grey rock, rising in noble buttresses and grey ribs like something in the Hebrides. Looking along it, my eye caught skeletal ribs on top of a pinnacle—the dramatic ruins of Fast Castle.

This had to be my target, and the map showed a farm track off the A1107 to Dowlaw Farm. At the end of the three-mile track I parked and set off on foot along the grassy footpath traversing north-east and dropping from 500 feet to the hidden precipices of the coast.

I had been here years ago, but not on this path which was built recently by Job Creation workers to encourage visitors to walk this bit of highly scenic coast. The splendid moment is when the stronghold perched on its crag is suddenly before you, loud with the wailing of kittiwakes, and below you is nothing but verticality, with the waves crashing and slunging at the bottom.

This place is all the more fascinating because no one knows who built it, but it was in existence 600 years ago and described as “fitter to lodge prisoners than folks at lybertie.” Jamie the Sixth would have been held captive in it if the Gowrie plot had succeeded. And before then, in 1503, Princess Margaret Tudor spent a night in it when on her way from England to marry James IV.

Archaeologists have been at work for years at Fast Castle, and numbered plastic pegs project from various excavations in the stonework. Perhaps they will locate the secret stairway which is supposed to lead down into a cave giving direct access to the sea. Or they may even find the hoard of gold brought from Spain 400 years ago to finance a Roman Catholic invasion of England from the Scottish side of the Border.

Much of the original castle was destroyed and rebuilt, and we hear of its wild occupant, Logan of Restalrig, notorious for theft, murder, treason and rebellion, striking a strange bargain in 1594 with scientist John Napier to search and locate the hidden treasure of Fast Castle.

Napier, the inventor of logarithms and the greatest brain of his time, was a firm believer in the occult. But not even the sacrificial gesture of killing a black cockerel helped the mathematical genius to find the gold.

Walking back to the car, we met the shepherd of Dowlaw, who herds cross-Suffolk sheep on these uplands. I asked him if the building and signposting of the path had brought a rush of visitors. He said it had, that even the odd busload of school children came now. He felt, however, that Fast Castle was as far as they should be encouraged to go because of the danger of a fall over the cliffs.

I agree with him; the coast east¬ward is great fun for a rock- scrambler who can enjoy the sensational pinnacle of the Souter and the arête of the Brander, but the ordinary walker is safer keeping more inland. The easiest way to see the best bird cliffs to is go back to the Coldingham road and take the right of way path from St Abbs to the Head.

The perched fishing village of St Abbs with its wee wynds, old houses and busy little harbour, makes the perfect introduction, the walk itself taking less than an hour to the lighthouse built in 1862. Westward rise the highest cliffs in Eastern Scotland, where submerged reefs have caused many a storm-tossed ship to founder.

St Abbs is said to have got its name from a lady who survived shipwreck—St Ebba, a Northumbrian princess. In thanksgiving for her deliverance a monastery was built on the headland. St Cuthbert visited her in 661 A.D., and prophesied the doom of the monastery by fire for the sin of monks and nuns living under one rule. It came true when invading Danes swooped on the monastery, burning and ravishing. The story goes that the nuns disfigured their faces to preserve their chastity.

Talking to Mr Tom McCrow who farms Northfield but has made an arrangement to run the St Abb’s Head part of his property as a Scottish Wildlife Trust Reserve, he told me he had done it in the interests of the seabirds, flowers and the shore life in an area which is becoming ever more popular. It is the old problem in the age of the motor car of allowing reasonable access without encouraging an excess of tourists. A ranger service helps, and field naturalist George Evans, on duty from April to September, patrols to give advice and help visitors enjoy the place without detriment to the wildlife.

It was there I heard of the Countryside Commission plan for a long distance walkway beginning at Portpatrick in the extreme west of the Dumfries and Galloway Region and crossing through the Border Region to come out at Cockburnspath. Looking at the detailed map, it took the exact line of the Border Walkway from Moffat to Galashiels, the enjoyable sixty-mile route which I described in this magazine when my wife and I were given the honour of being the first to walk it, by courtesy of the Border Hillwalking Club.

I’ve been hearing how the west and east bits link up from Mr Bill Prior, Secretary of the Countryside Commission, who thinks the route could be a fact by 1982 if the Secretary of State for Scotland approves the detailed plan— £150,000 would have to be spent on the 204-mile traverse.

I was delighted to find that I had already walked other bits he outlined, and I think the whole concept is absolutely first class. Beginning at Portpatrick and turning your back on Northern Ireland, with the Mull of Kintyre just across the water, you go through Galloway by the smooth farming greenery of the Rhinns and approach The Moors by Castle Kennedy, enter Glen Trool at Bargrennan and head east by Loch Dee and Clatteringshaws to Dairy.

You head for the Nith at Sanquhar and go by Wanlockhead and over the Lowthers to Beattock for Moffat. Now you are on the Border Walkway for 60 miles. In the November issue of 1975 I described the route by the Wamphray Water and Selcoth Burns to Ettrick Head and over the hills to St Mary’s Loch, by Blackhouse to Traquair, then across the Minchmuir and so to Galashiels.

Melrose and Gattonside lead you on to Lauderdale, thence along the Lammermuirs to Abbey St Bathans and by the wee harbour of Cove to Cockburnspath. No other walk in Scotland is likely to take you through a bigger chunk of history or more varied scenery, some of it so lonely that bothies will have to be built. It sounds a great prospect, beginning on the Atlantic side and finishing on the most splendid fringe of Scotland’s North Sea coast.

- The Scottish Sea Bird Centre provides video links to the birds on the Bass Rock. Photo by ROB MCDOUGALL www.RobMcDougall.com 07856222103 info@robmcdougall.com

More…

Read more from Tom!

We have an extensive archives of Tom Weir’s great columns for The Scots Magazine, and we’re slowly but surely getting them published digitally for new generations to enjoy.

To see the columns we have online so far, click here.